As one of Dirk Bogarde’s finest films is restored and re-released, JAMES OLIVER explores one of Britain’s greatest – and most complex – acting talents, who let his choice of roles do the talking.

There have always been differences in style between Hollywood and its British equivalents but rarely were they so pronounced as they were in the mid-1950s.

In America, these were the years of Marlon Brando and James Dean, method actors who challenged authority on-screen and off. British cinema, by contrast, was dominated by clean-cut young men who didn’t want to rock the boat. Chaps wearing Harris Tweed sports jackets rather than biker leathers.

Chief amongst these agreeable fellows was Dirk Bogarde. He first captured the hearts of British audiences with Doctor in the House, the ne plus ultra of amiable light comedy and quickly became the housewives’ favourite.

The ‘idol of the Odeons’, they called him; so far away from the brooding Brando that contemporaries might find the comparison comic.

Then again, those contemporaries didn’t have the advantage of hindsight. From the vantage point of the 21st century, it’s not fanciful to say that Bogarde numbers amongst the very greatest screen actors this country has ever produced, a man who foreswore easy stardom for more challenging fare that allowed him to explore the contradictions and complications that drove him.

He was born Derek van den Bogaerde – his family was of Flemish descent – in 1921, and after an unhappy stint as a commercial artist, he followed his heart. He become an actor, but didn’t get very far before war broke out. Wanting to do his bit, he joined up and served (with some distinction) in military intelligence, analysing aerial photographs to pin-point potential targets for bombing raids.

He realised the consequences of this work when he went out in the field after D-Day and saw what remained of Europe, a desolation he knew he was in some small way responsible for. By his own account, worse was to follow: he visited Bergen-Belsen soon after its liberation and saw for himself the grim reality of the Final Solution.

He would return to acting after demob, and this time he was luckier. A talent-spotter from Rank studios saw enough potential to snap him up and, after being re-christened with an easier-to-pronounce stage name and given rudimentary training at the so-called Rank ‘Charm School’, he was set before the cameras.

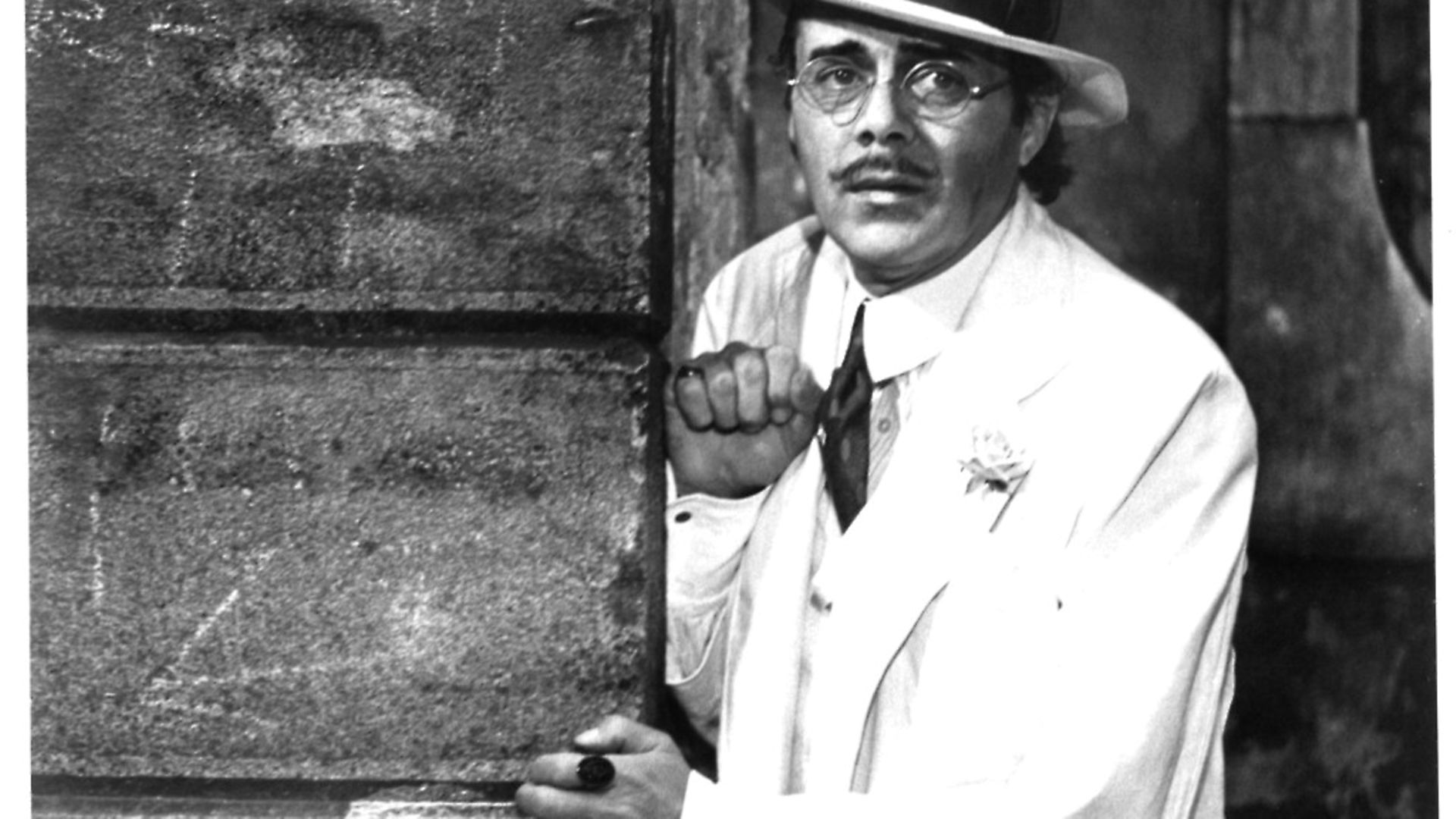

Although most famous as the sort of chap you could take home to mother, Bogarde’s early screen roles were in less sympathetic parts. For some reason, Rank studios reckoned this well-spoken former officer was good casting as a no-good spiv; he played the toe rag that plugs PC Dixon (later of Dock Green) in The Blue Lamp, for example, possibly the most shocking moment in the whole of British cinema.

It took a year or two to recognise his talents lay in other directions, until Doctor in the House and the resultant success. As the fan mail mounted, so more films were planned; now they recognised they had a thoroughbred under contract, Rank were going to put him to work.

The films he made in those days are, for the most part, negligible. If Doctor in the House endures through regular television screenings, then Simba and The Spanish Gardener are more obscure, with good reason, epitomising as they do the bland, parochial quality of so much British film of this era.

That hardly stopped them becoming hits, though – something more easily attributed to Bogarde’s breezy charm than the quality of the scripts. But what those who bought tickets didn’t realise was how much of that breezy charm was performance.

He’d always had a sharp tongue and became ever more acidic with success, gaining a reputation for being difficult on set, lashing co-stars and crew members alike with his waspish wit or worse; he took against John Mills during production of The Singer Not the Song for seemingly no reason at all, treating his bewildered co-star with sneering contempt.

The studio (if not John Mills) took all this in its stride – stars had, after all, been temperamental since time immemorial – and duly tried the traditional remedy, which is to say, offering him more money. Bogarde’s truculence, though, was a symptom of a deeper discontent: creative types – those worth bothering with, at any rate – are always motivated by more than cash. The films he chose to make next show how desperately he wanted to escape from Rank’s gilded prison.

Bogarde wasn’t the first choice for Victim (1961). He only became involved after other actors had dropped out or rejected it outright; the more honest of them admitted it was because they were frightened what such a role might do to their livelihood, for the script concerned homosexuality and such things were still against the law then, let alone tolerated.

Bogarde – finally free of his studio contract – was considered to be risking his career and reputation by taking the role: it says much that he went ahead and did it anyway, playing the barrister fighting the blackmailers of a young man with whom he has had a deeply emotional relationship. The young man commits suicide after being arrested for embezzlement, rather than ruin his beloved’s career. But Bogarde’s character risks his reputation and marriage to expose the extortionists and see that justice is done. Victim was the first British film to portray the humiliation gay people were exposed to.

It should be noted that Bogarde himself was gay, although, as one might expect from a man of his time, he was never so open about it: he himself characterised his four-decade relationship with his manager Tony Forwood as simply a ‘friendship’. People drew their own conclusions, of course, but Bogarde always declined to confirm them.

Still, it’s not fanciful to see Victim as a declaration. Certainly it was a defiant statement of artistic freedom: while he did not abandon commercial cinema entirely, he concentrated thereafter on more rarified films, very different to those he had made before.

What, for instance, did his suburban fanbase make of The Servant? Directed by Joseph Losey, a refugee from American anti-communism, it is the story of a minor aristocrat manipulated by his manservant and a landmark in British arthouse cinema; a study of power relationships and mind games that’s a very long way from Doctor in the House.

Many stars talk a good game about making small, more artistically minded pictures but Bogarde actually did it. What’s more, he took roles very different to those that made his name: Bogarde would once have been the logical choice to play the employer; instead, post-Victim, he was playing the title character, Barrett, drawn to the contradictions of the part and perhaps more; alternately fawning and spiteful, Barrett is not so far from Bogarde himself, a man who knew how to both seduce and wound with equal ease.

Bogarde never renounced commercial cinema – he was part of the all-star line-up in A Bridge Too Far (1977) – but he preferred films where he could play characters troubled by dislocation and discontent.

In the absence of statements to the contrary, it’s tempting to suggest he sought roles that allowed him to present how he really felt and explore feelings he couldn’t easily articulate in other ways. (Perhaps significantly, he became much less acerbic too.)

This came at the cost of his domestic popularity but if audiences in Britain were sniffy about Bogarde’s changing priorities – there would always be those who hankered for how he used to be, before he went all weird – he attracted new admirers elsewhere.

Amongst them was Luchino Visconti, Italian director of Senso and The Leopard. They first collaborated on The Damned and then, more fruitfully, on Death in Venice.

Recently restored and released on Blu-ray, Death in Venice rests entirely on Bogarde’s shoulders, or rather his eyes; his character – a dying composer fascinated by / attracted to a beautiful youth – scarcely speaks, but he doesn’t have to.

“The camera can photograph thought,” Bogarde once said: he proves it here.

He would continue to work with bona-fide auteurs, in roles richer than the mainstream could offer: for Alain Resnais (in Providence), for Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Despair), for Liliana Cavani (The Night Porter). (Note how many conflicted characters he played; men with hidden natures or divided against themselves.) But acting interested him less.

He started to write, first memoir, then (well-received) novels. These were not confessional works: his books deflect as much as they reveal, polishing anecdotes to show only as much as he wanted to.

He was a closed man, and it’s hard to unpick his motivations even now, some 20 years after his death, although explanations can be glimpsed: his descriptions of the war, most especially his visit to Belsen, suggest trauma; chaps didn’t talk about the beastliness of war back then – stiff upper lip and all that – but it evidently scared him profoundly. And there’s his sexuality of course, necessarily concealed in a less permissive age. But he remained elusive to his end in 1999, no matter how hard people tried to pry: “I’m still in the shell, and you haven’t cracked it yet, honey,” he told chat show host Russell Harty, declining to surrender control over his own narrative.

The closest we can get to him is through the roles he chose in the second half of his career. His characters are seldom likeable – itself an admission of sorts from one who was so famously charming – but are always complex, questioning and troubled by their failings. Paradoxically, this most private of men revealed himself most fully on screen.

Comparisons to Brando are not so fanciful as they might seem at first sight: both were thinking, feeling men – artists not always well-served by the material they were given. And both were amongst the best there’s ever been.

The restored Death in Venice is now available on Blu-ray, from The Criterion Collection.