Released 40 years ago and now the subject of its own exhibition, The Clash’s London Calling simultaneously paid tribute to rock ‘n’ roll and took an iconoclast’s Hammer to it. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports.

When Boris Johnson claimed in his first party election broadcast of the 2019 campaign that his favourite band was The Clash (either them or the Rolling Stones, he unconvincingly claimed), it sounded like a line cooked up in a Tory HQ brainstorming session. Not since Johnny Rotten fronted a butter advert has punk been so shamelessly co-opted.

Punk’s status as a great British export and shorthand for cultural edginess (signalling, therefore, being ‘in touch’) is grist to the political image-making mill, and The Clash were presumably deemed entry-level punk by aides and a name that would be known by the British public at large.

The political message the band tried so earnestly to promote (indeed, Rotten condemned their songs as “Just a few quotes from Karl Marx around a merry little melody”), was completely elided – one doubts Johnson is fully on board with the socialist Joe Strummer’s songs about the Nicaraguan Sandinistas and the Spanish Civil War – and The Clash became mere cardboard cut-out ‘punk icons’.

While the band are celebrated in a more three-dimensional manner in a new Museum of London exhibition marking the 40th anniversary of the release of London Calling, reverent treatment can bring its own problems.

Their weighty posthumous reputation sees their ‘relics’, including the splintered Fender Precision bass Paul Simonon wields in Pennie Smith’s photo on the LP’s (yes – ‘iconic’) cover, put on show for the faithful. Ephemeral minutiae, including scraps of paper with fragments of Strummer’s handwritten lyrics, appear not only in the exhibition but have been published as quasi-sacred texts in Sony Music’s anniversary cash-in London Calling Scrapbook.

This kind of worship can frustrate a real understanding of a band’s failings and achievements, and while London Calling was The Clash’s greatest moment, this was in large part because it came after critical ignominy and creative meltdown. The album turned out to be a prediction of the turbulent 1980s, and it is a record that speaks to the future still.

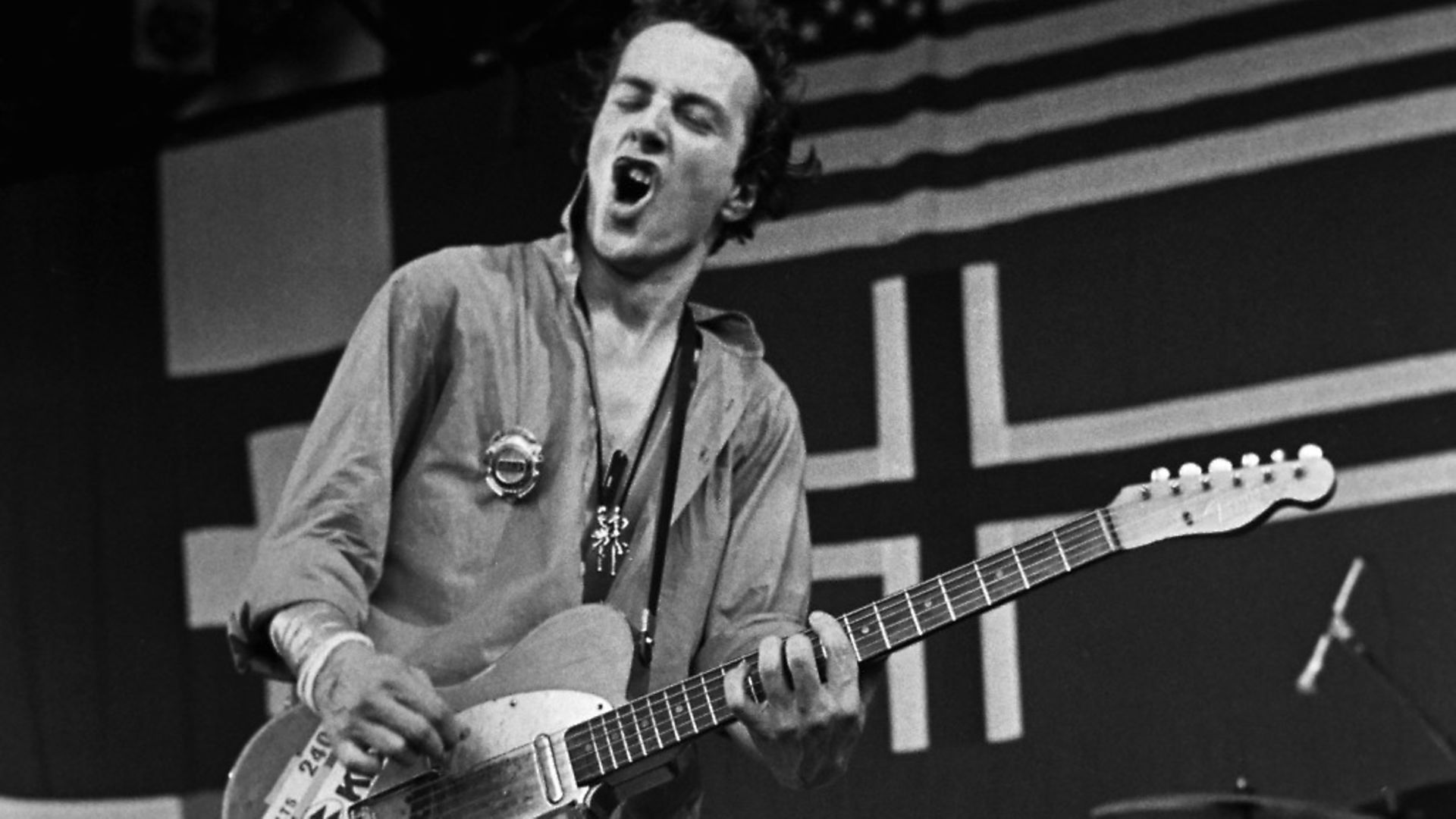

The Clash were an all-round controversial proposition in 1979. While the “punk police”, as Strummer put it, saw their big-money signing to CBS in early 1977 as strangling the true punk spirit at birth, for everyone else their live ferocity and political militancy made them synonymous with danger.

CBS had bottled releasing their eponymous 1977 debut in America, thinking the country wasn’t ready for raw British punk. In fact, the LP’s punk anthems like Janie Jones and White Riot saw it do a massive 100,000 copies in sales as an import, but 1978’s Give ‘Em Enough Rope would be their first official US release.

It was an overt attempt by CBS to make The Clash presentable for America. With Sandy Pearlman, then best-known for his work with Blue Öyster Cult, drafted in by the record company to produce the album, out went grubby spontaneity and in came a more reflective mood and higher production values, with Pearlman doing far more to the band’s sound than just knocking off the rough edges.

The shift in the flavour of The Clash between their debut and Give ‘Em Enough Rope was mirrored in the album covers. The black and white directness of Kate Simon’s alleyway portrait of the band – all lean angularity – gave way to a garish image of a Chinese horseman looming over a cowboy being eaten by vultures (a visual metaphor for the end of capitalism – what else?).

There were hard-hitting themes – terrorism, the National Front, police infiltration of the left, drug addiction – but there was also evidence the band had already succumbed to the corollary of rock ‘n’ roll life – navel-gazing, with songs about recent mishaps on a trip to Jamaica and misty-eyed school days reminiscences.

The critics panned the LP as a sell-out. The NME’s Nick Kent derided “Strummer’s totally facile concept of shock-politics”, while Jon Savage wrote in Melody Maker simply “they squander their greatness”. And it hadn’t even been worth it, as the album sold well in the UK but missed the Billboard Top 100 altogether. The Clash faced 1979 – the year punk seemed to die with Sid Vicious – in need of a credibility boost and without direction.

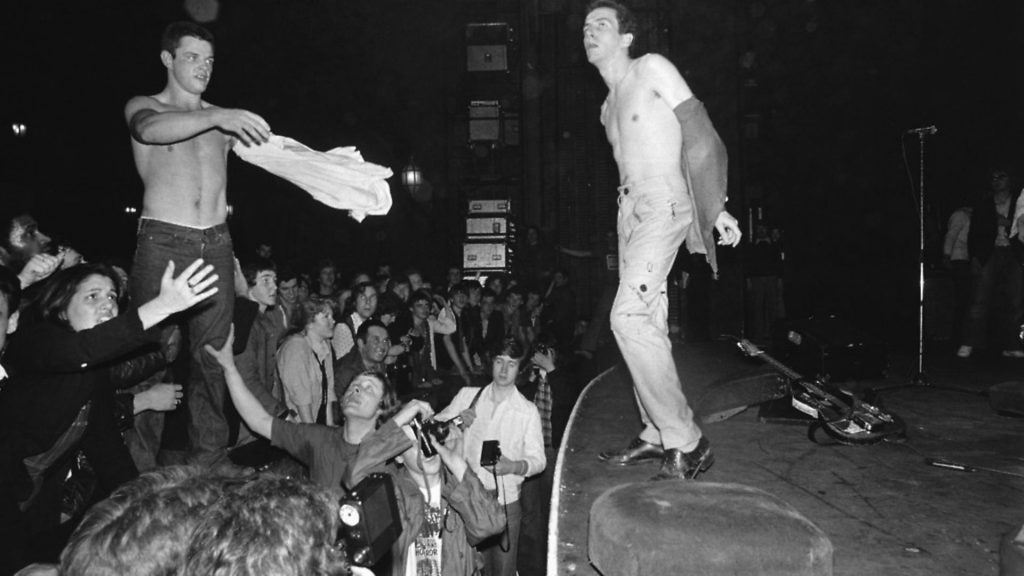

London Calling was born round the back of a Pimlico garage as the band holed up at an obscure studio for a protracted period of writing and rehearsals. There they rediscovered their creative chemistry and confidence, and restored their camaraderie via five-a-side football matches on a nearby recreation ground.

When they went into Wessex Studios in August, it would be with a clutch of songs and a new sense of purpose, but it was their producer – this time one chosen by them and not imposed by their record company – who would set the tone for London Calling.

Guy Stevens was known for his work with Mott the Hoople (The Clash’s guitarist and songwriter, Mick Jones, had been a teenage fan and was near-obsessed with the band), and was a man with an ego as big as his drink problem, once saying “There are only two Phil Spectors in the world, and I’m one of them”.

Stevens encouraged feel over technical precision and lent the London Calling sessions an edge of chaos, chucking furniture around the studio as the band played.

He started as he meant to go on in encouraging the band to take a relaxed approach to things. The very first song of the sessions was a rambunctious psychobilly cover of tragic rock ‘n’ roller Vince Taylor’s Brand New Cadillac. Played merely as a warm-up, Stevens recorded the run-through and proclaimed it the take for the album. When drummer Topper Headon pointed out the tempo changed as the song progressed, Stevens responded: “All rock ‘n’ roll speeds up!”

With such tricks Stevens, who would die of an accidental overdose at 38 two years after London Calling was recorded, completely relieved the pressure of trying to make a reputation-redeeming record, freeing the band to make something as loose as their debut had been pent-up.

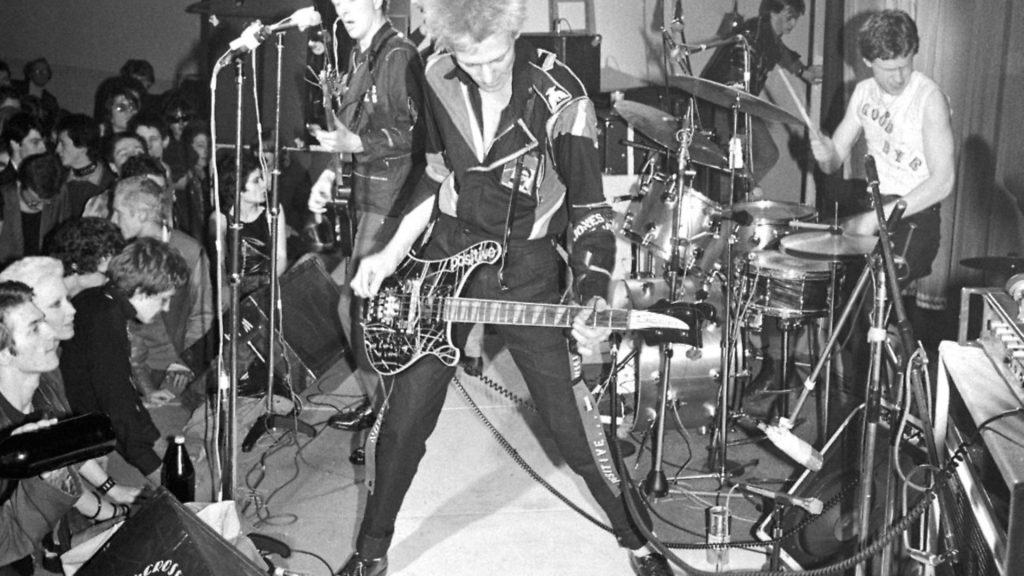

On its release, London Calling emerged as a sprawling 19-track double album with a bewildering mix of influences drawn from the band’s diverse interests, rockabilly, reggae and jazz among them. Yes, it was sometimes a cacophonous miscellany and was not exactly devoid of filler, but it was also vital, unpredictable and intriguing, rollicking along on its own enthusiastic energy and capturing a band finally cooking on gas.

Where Give ‘Em Enough Rope was staid and stale, London Calling was free and fresh, and it was an incredible sonic shift from their debut of just two-and-a-half years before.

Rechannelling the roots of rock ‘n’ roll, it was a complete about turn from the band’s original mantra of ‘No Elvis, Beatles, or The Rolling Stones’.

This certainly was no revolutionary record, particularly when compared to 1979’s stark releases by Joy Division, Public Image Ltd. and Wire, among others, but in its use of pastiche, there was art.

The design for the cover of London Calling by NME cartoonist Ray Lowry summed up what was going on inside the sleeve, simultaneously paying tribute to rock ‘n’ roll and taking the iconoclast’s hammer to it.

It used the distinctive pink and green typeface of Elvis’ 1956 debut album, and the bass-smashing cover photo – out of focus and full of momentarily suspended violence – was an inversion of the image of Elvis mid-note, toting an acoustic guitar, from that record of quarter of a century before.

Taken together, the two covers symbolised the beginning and the end of rock ‘n’ roll. Ads for the album in the music press went fully meta, with a young, lamé-suited Elvis shown holding the Clash’s record. This imagery took the punk bricolage approach to another level, and that was true of the record sonically too, making London Calling more than just a jumble of covers and snatches of the musical past.

Brand New Cadillac was the record’s boldest refashioning of rock history, but it continued elsewhere on the record too. The Card Cheat saw Guy Stevens fully indulge his Phil Spector fantasies, with a lush ‘wall of sound’ effect achieved by dubbing one full take over another, while Jimmy Jazz had jazz guitar and the clear feel of a band jamming without the pressure of projecting an attitude.

I’m Not Down referenced the bassline of the Kinks’ Waterloo Sunset (1967). The cover of ska song Wrong ‘Em Boyo and the exuberant celebration of Rude Boy culture on Rudie Can’t Fail slotted the band into the territory of 2-Tone, which was taking off as the LP was released.

For all this breaking into new territory, The Clash still held on to their politics and their anger, fuelled by the violence and injustices of the decade that was ending.

Clampdown incited action against establishment oppression (“Let fury have the hour, anger can be power/ Do you know that you can use it?”), the melodic Spanish Bombs referenced the Spanish Civil War, by way of ETA and IRA bombings, and Paul Simonon’s The Guns of Brixton advocated push back against police brutality (“When they kick at your front door/ How you gonna come?/ With your hands on your head/ Or on the trigger of your gun?”).

Consumerism was a theme on the advertising jingle-inspired Koka Kola, as well as Lost in the Supermarket, which also referred to the difficult childhoods of Strummer (a diplomat’s son and early boarder) and Jones (brought up by his grandmother) – “I wasn’t born so much as I fell out/ Nobody seemed to notice me”.

But all of this paled beside the title track. Its first four bars were among the most atmospheric ever recorded, even if it was heavily ‘inspired’ by the Kinks’ Dead End Street (1966), somehow evoking the seething city streets and full of foreboding. The lyrics went on to outline an apocalyptic vision of “zombies of death” and “nuclear error”, where “war is declared and battle come down”, punctuated by Strummer’s feral dog howls.

It was a questionable bit of album sequencing to make the title track the opener – the rest of the record couldn’t hope to live up to it. London Calling reached No.11 in the UK singles chart in January 1980, becoming the band’s highest-climbing ‘in-service’ single (ironically, these prophets of anti-consumerism got their only No.1, Should I Stay or Should I Go, nearly a decade after their acrimonious break-up, on the back of a 1991 Levi’s ad).

London Calling was a critical smash and a complete exorcising of The Clash’s ‘difficult second album’. Tom Carson of Rolling Stone wrote that, on the evidence of London Calling, The Clash were “the greatest rock ‘n’ roll band in the world”, while the NME’s Charles Shaar Murray said simply “This is the one”. Only Garry Bushell of Sounds panned it as a chaotic mix of amateurishly-rendered pastiches, condemning the band as “second-rate Stones copyists”.

The band can’t have much cared, having regained creative form and even managed to score a victory over their record company by getting CBS to price the double album as a single LP, benefitting the music-buying man and woman in the street.

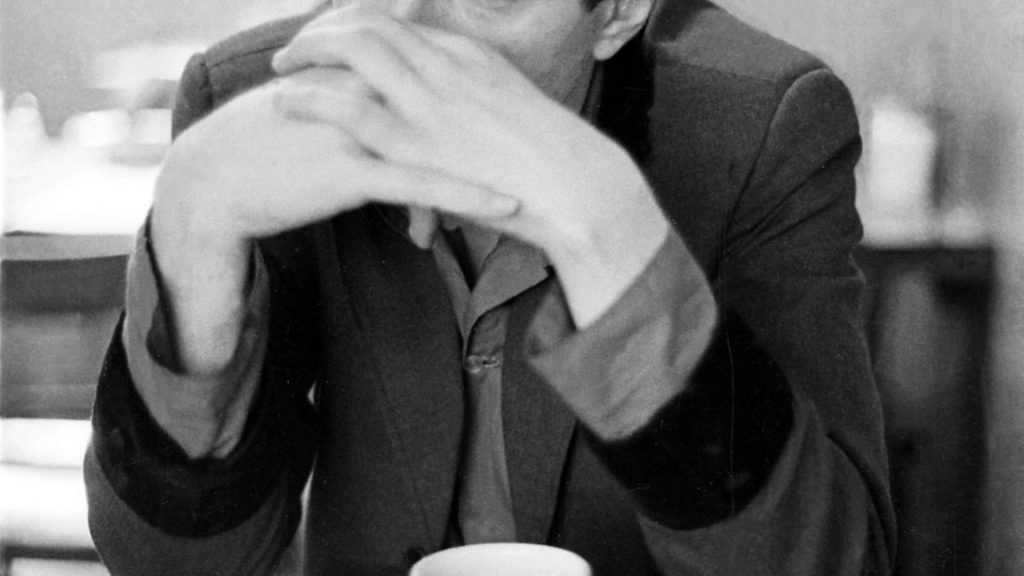

Today, the LP is considered the band’s masterpiece, gaining further mystique when Strummer died suddenly just before the Christmas of 2002, aged just 50, and entered the pantheon of rock legends.

As the 1980s dawned, London Calling seemed prophetic. Thatcher’s Britain and Reagan’s US saw the band’s full list of political and social evils enshrined. The Guns of Brixton foreshadowed the riots of 1981.

As we once again stand on the threshold of a new decade, the album retains its relevance, particularly that title track that stands head and shoulders above the rest. 1979 was the year of the First World Climate Conference, a fact that Strummer – an early adopter of environmentalism as a co-founder of the Future Forests tree-planting project – was unlikely to be aware of when he wrote lyrics that nonetheless seem to detail the apocalyptic reality of climate change, a force which will define the next decade and beyond: “The ice age is coming, the sun is zooming in/ Meltdown expected, the wheat is growing thin/ Engines stop running, but I have no fear/ ‘Cause London is drowning, and I, I live by the river.”

The Clash: London Calling is at the Museum of London until April 19, 2020