Two years after the archipelago’s most famous journalist was blown up by a car bomb, calls for justice are louder than ever. CAROLINE MUSCAT reports on a disturbing case the represents a national disgrace.

Daphne Caruana Galizia sent me a text message a few days before she was killed. It read: “I have a sense of time running out… so many things I wanted to do.”

She had already endured so much. Her front door was set on fire in 1995 and her dog’s throat was cut. In 2006, tyres were piled against the back door of her house and set on fire with the family inside, an attempt on her life which was only foiled by the chance arrival home of one of her sons. She was regularly insulted in the street by government supporters, and served with a seemingly endless series of libel suits by the politicians and businessmen she wrote about.

“What else are they going to do, Caroline?” she said. “Blow me up?”

That’s exactly what happened a few weeks later.

Daphne was killed by a massive car bomb that had been placed under the seat of her car. They murdered her just down the road from her home. Contrary to initial reports, there were two explosions, not one. The first tore her leg off, but she’d only just begun to scream when, seconds later, a larger explosion engulfed her car in a ball of fire.

My first reaction was numbness. A journalist’s instinct is to rush to the scene, and it was only ten minutes away; but I just sat there, shocked.

The brutal murder of Malta’s leading independent journalist plunged our country into a state of shock, but not surprise. Many of Daphne’s readers feared it might come to this.

A former judge at the European Court of Human Rights, Giovanni Bonello, a staunch defender of human rights in the country’s darkest times, wrote in his contribution to the book Invicta: The Life and Work of Daphne Caruana Galizia, published a few weeks after her death: “I had no doubt that Daphne Caruana Galizia would be killed. This is Malta, and no one should expect integrity and fearlessness to go unpunished.”

The year before she was killed, Politico named her as one of the 28 people most likely to shape Europe in 2017. They described her as: “A one-woman WikiLeaks, crusading against untransparency and corruption in Malta, an island nation famous for both.”

She investigated corruption at the highest levels of government, exposing scandals that continue to plague the administration of the current prime minister, Joseph Muscat, including serious allegations of corruption in his inner circle.

Muscat protected those at the centre of the storm, including his chief of staff, Keith Schembri, and tourism minister Konrad Mizzi, who Daphne exposed as owning secret companies in Panama, an allegation that was confirmed by evidence revealed in the Panama Papers.

It’s been two years since Daphne was assassinated, but we’re still no closer to finding out who wanted her silenced. And the very people she wrote about are the people in charge of the investigation.

The prime minister was interviewed by international media within hours of the bomb blast. “She was probably my biggest adversary,” he said, “she attacked me from when I was leader of the opposition. But that was her job.”

It is a strange way to characterise a journalist, but then, Muscat’s references to her in the aftermath of her murder were often deeply personal. In many ways, Daphne was Joseph Muscat’s nemesis.

A criminal investigation and magisterial inquiry are still continuing, but the country is no closer to knowing who wanted Malta’s leading investigative journalist silenced.

Three months after Daphne’s death, the police arrested ten individuals in what resembled a Hollywood-style production, complete with masked commandos, helicopters and helmet-mounted cameras, a far cry from the more familiar low-budget productions of the Malta police.

We do not know what happened to seven of them, but three were charged with planting and triggering the bomb that killed her. Vincent Muscat and the brothers Alfred and George Degiorgio were arrested a few months after her death. Almost two years down the line, they have not said a word and the trial has not even begun.

The compilation of evidence revealed that one of the three suspects had scribbled the telephone number of his partner on his arm with black marker. Did he do this every morning, or only on that morning? And why did the suspects decide to throw a bundle of mobile phones into the sea right next to their shed, instead of outside the harbour where they were less likely to be found? Had the three men been tipped off that the police were on the way? There are many unanswered questions.

The police seem no closer to identifying who ordered the murder. They’ve also failed to interrogate any of the politicians Daphne investigated and exposed.

The magisterial inquiry has also been the subject of controversy. Police sources working on the criminal investigation even admitted planting false evidence with court experts appointed by the inquiry, saying that their goal was to expose ‘moles’. Despite it being an offence to tamper with evidence, no action was taken.

Instead, prime minister Muscat promoted magistrate Anthony Vella to judge, a career advancement that meant Vella had to abandon the magisterial inquiry before its conclusion. Another magistrate then took his place in an inquiry tasked with preserving evidence that can lead to an understanding of who commissioned this assassination.

Concern over irregularities in the investigation led the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) to set a three-month deadline for Malta to hold “an independent and impartial public inquiry” tasked with determining whether the state could have acted to prevent Daphne’s death, and whether the state knew, or ought to have known, of a real and immediate risk to her life. It will also look into whether criminal provisions are sufficient to protect others at risk.

Muscat had already raised doubts about his intentions by dragging his heels until the very last minute, delaying and avoiding and making excuses – and even issuing passive-aggressive threats: “I definitely will not be the person to shoulder responsibility if a public inquiry and its process ends up destroying the current case against the three arrested persons,” he said. But now he was in a corner.

The government announced the public inquiry on a Friday evening, a few days short of the Council of Europe deadline, and hours after the island’s newsrooms had closed. The press release was picked up, uncritically, by national and international wire services, from BBC World to the Fiji Times, even as journalists in Malta scrambled to look into the members Muscat had appointed to the Board of Inquiry and the terms of reference set by the prime minister whose government this inquiry is supposed to scrutinise.

But the tactic worked. Muscat bought himself more time. In Malta, perception often matters more than reality. It is a trademark of the Muscat administration to give the impression that it’s open to checks and balances while ensuring that anyone who makes those decisions is firmly under control.

Malta’s laws look good on paper, but it was only when the Council of Europe special rapporteur Pieter Omtzigt, a Dutch MP, started work that the truth was revealed.

Omtzigt found an alarming lack of distinction between party and state. His report, published in June 2019, revealed that most regulatory bodies and law enforcement entities in Malta are directly accountable to the prime minister. Those who don’t answer directly to Muscat on paper owe their appointments and continued livelihoods to him in practice. And Muscat has been careful to place Labour Party loyalists in every key role.

The law on public inquiries in Malta gives the prime minister the power to appoint its members, even when it comes to the long sought-after public inquiry into the assassination of an investigative journalist who was the government’s – and Muscat’s – harshest critic.

The members of the Board of Inquiry appointed by the prime minister immediately made headlines, raising concerns about whether the government’s efforts to find and bring to justice the mastermind(s) who ordered the journalist’s assassination were in fact genuine, or whether this inquiry would be nothing more than State-sponsored reputation washing.

The government also failed to consult the victim’s family on who would be tasked with investigating Daphne’s violent death, a move that runs contrary to Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which states that consultation on the Board’s membership is an obligation owed to bereaved next of kin.

“The Board will be unfit for purpose if the public has reason to doubt any of its wider members’ independence or impartiality,” the Caruana Galizia family said in a statement. “We ask to meet with the prime minister without delay to discuss our concerns in that regard.”

Special rapporteur Omtzigt recently reinforced these concerns in Strasbourg. “In my view, the inquiry as currently constituted clearly does not meet the Assembly’s expectations. I intend to continue following the situation in advance of the next meeting of the Committee {on Legal Affairs and Human Rights on November 14 2019}.”

The government responded immediately with a statement of its own, issued only in Maltese. It doubted Omtzigt’s integrity, implying he had a credibility problem and suggesting his statement was “full of inaccuracies”.

The country may have gone into deep shock after Caruana Galizia’s brutal murder, but even as her assassination made international headlines, government supporters met the news with calls for “celebration”.

An investigation by the press into the online hate machine that targeted Daphne Caruana Galizia revealed secret and closed Facebook groups totalling 60,000 members, built by the Labour Party over a period of seven years. Anyone wanting to join these groups had to show evidence of party membership, and Daphne was their favourite target. They called her “sa??ara ?adra” (an evil witch), and members were free to say she should “burn in hell”.

When news of the car bomb spread, members posted statements including: “she got what she deserved”, “what goes around comes around”, and “she can’t rest in peace because she’s in pieces, she can’t even be buried, karma is a bitch”.

They called for a “street party” on the day of her funeral, with loud music and celebratory drinks, calls to wear red (the Labour Party’s colour), and posted more memes of witches burning at the stake.

These were not anonymous gatherings of extremists. The former president of Malta, Marie-Louise Coleiro Preca, the prime minister Joseph Muscat, and eight of his senior staff were members of these groups, where Muscat is worshipped as “il-King ta’ Malta” (the King of Malta), and where the personal details of anti-corruption activists were distributed, along with calls for them to be physically attacked, sexually assaulted and stalked.

The former president and the prime minister eventually left the groups after being questioned in parliament, but those groups continue to operate. One of the largest was reactivated in the lead-up to the 2019 European parliament elections in order to attack opposition candidates, dissidents, journalists and critics.

Pro-government trolls also continue to attack Daphne’s son, Matthew, who ran to the bomb scene from their home, barefoot, and tried desperately to pull what was left of his mother from her burning car. He was to blame for her death, they said, because he had parked her car in a place where those who planted the bomb could get at it.

The government has done nothing to stop this. On the contrary, it has failed to hold public officials accountable who continue to denigrate her, defending their comments as “freedom of expression”.

As the investigation drags on, the government is making every effort to wipe out Daphne’s memory by repeatedly removing a protest memorial to the journalist which was set up by citizens in front of the Great Siege Monument in Valletta within days of her death.

Individuals who approach the memorial are regularly harassed and insulted by those who were taught to see Daphne as a figure of hate. Nothing is done by the authorities, which only serves to encourage more abuse.

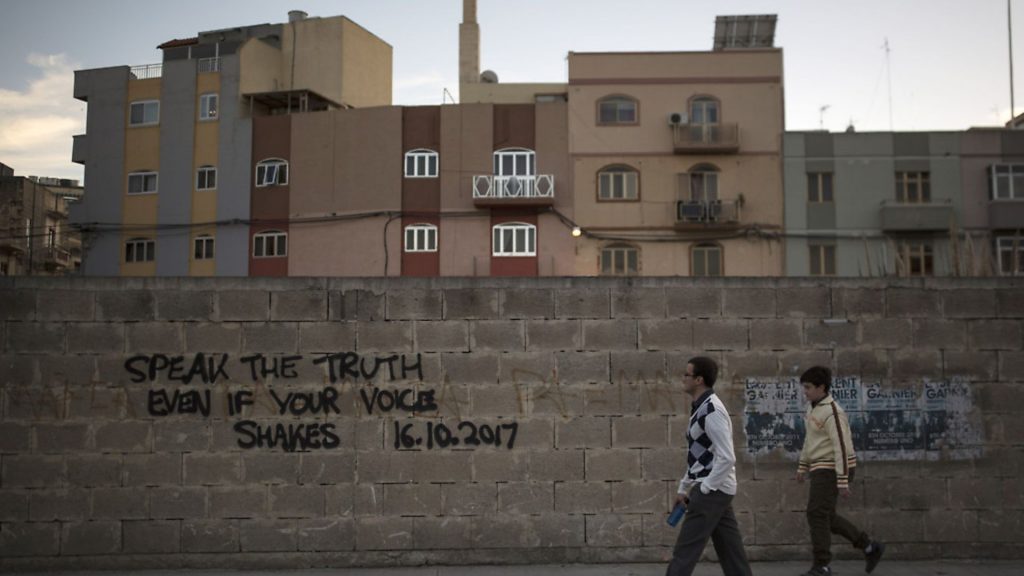

This monument has become a battleground between two clashing sets of ideals: the kleptocrats Daphne exposed and the civil society activists who fight, not only for justice for Daphne, but for the values she represented.

And so citizens leave flowers, photographs and placards at the protest memorial every day. And each night, employees from the government’s Cleansing Department take them away while the island sleeps, as though the dawning of a new day will wipe the slate clean of the journalist whose work this government wants to forget, and whose violent death it cannot escape.

Caroline Muscat is a Maltese journalist. She is the founder and editor of The Shift News

This story was first published by Tortoise. Copyright Tortoise 2019.

To read more slow journalism from Tortoise, become a member for £50 instead of £250 at tortoisemedia.com/friend and use the code “TNE50”.

Or get 13 weeks of The New European and one years’s Tortoise membership, all for just £25.