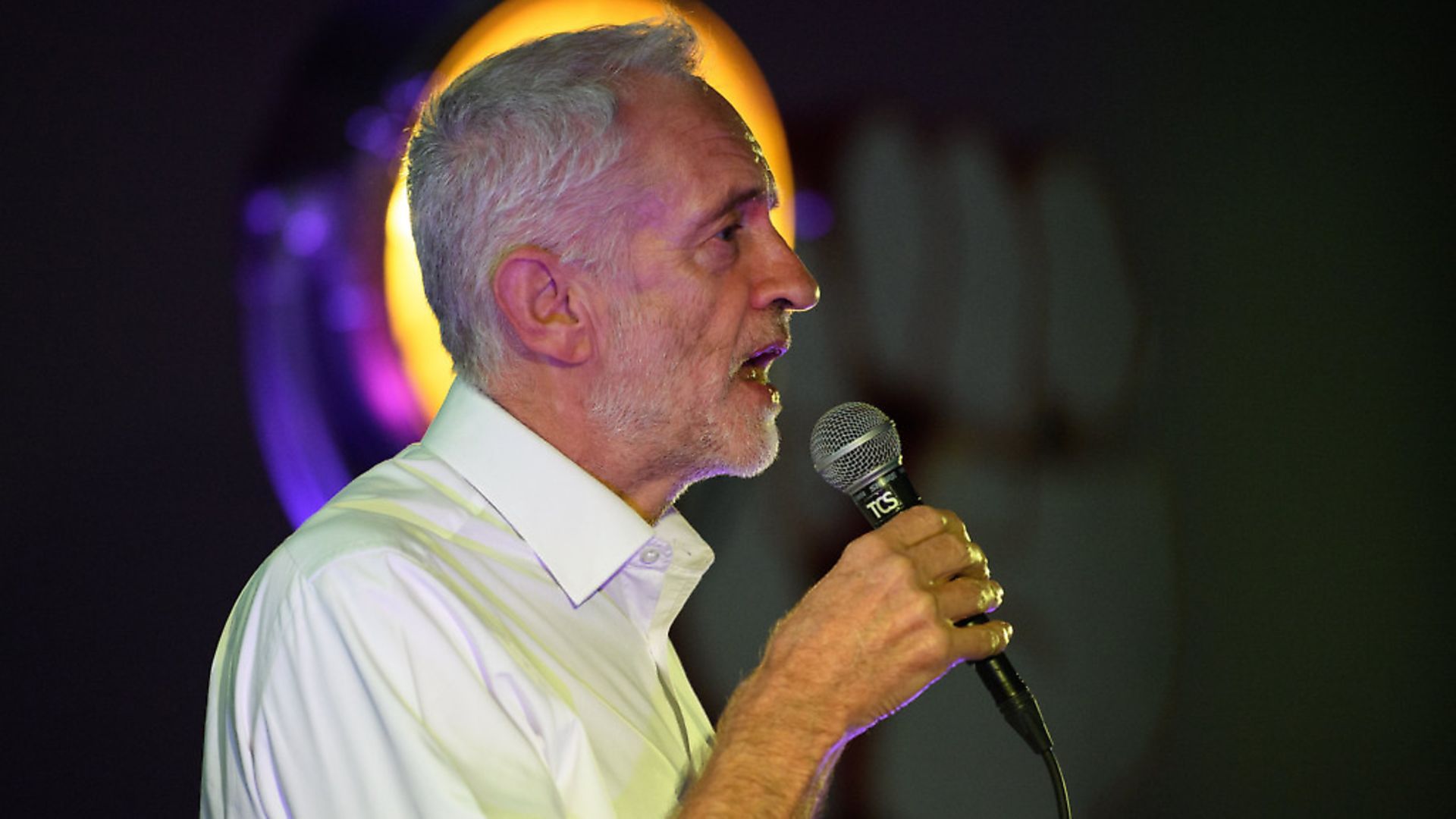

He might seem to have re-shaped left-wing politics in his image, but the Labour leader is still some way off creating the social movement needed to convert his vision into reality. STEVEN FIELDING reports

During his 2016 leadership campaign Jeremy Corbyn spoke to a packed meeting of supporters. ‘We are a social movement,’ he said.

Corbyn has certainly overseen a transformation of the Labour Party. From fewer than 200,000 members prior to the 2015 election, he is largely responsible for its rise to more than 550,000 by the end of 2017. By some distance, Labour is now the largest UK political party.

But, Corbyn claims, Labour is more than a conventional party. If it is, that is thanks to Momentum, to which 40,000 Labour members belong – an organisation which styles itself as ‘people-powered’ and fired by the ambition to ‘transform the Labour Party, our communities and Britain’.

Growing out of Corbyn’s 2015 leadership campaign, Momentum employs methods associated with those social movements in which many of its leading figures cut their teeth. Many believe these new ways of doing politics helped Labour do unexpectedly well in the 2017 election by mobilising once disengaged younger voters.

On closer inspection, however, Labour looks little like a social movement. And Momentum’s activities are more conventional than its leaders would have you believe. But if Corbyn is to achieve in government the radical changes for which the left has campaigned since the 1970s, a social movement is precisely what Labour has to become.

The Labour left always criticised the party’s established parliamentary focus and strategy of winning over floating voters by promising modest reforms because – they believed – it meant Labour would never achieve transformative change. To do that, generations of leftists argued, the party needed to look beyond Westminster and mobilise the active participation of millions behind a full-blooded socialist programme. For the left, looking beyond parliament would offset the timidity of their own leaders and the awesome power of capitalism.

When elected as an MP in the 1980s, Corbyn urged Labour to focus less on the parliamentary game and build a campaigning organisation. Instead the Labour leadership pursued the parliamentary road – a process that culminated in Tony Blair’s 1997 landslide. Two successive election defeats propelled Corbyn into the Labour leadership, still with an unchanged desire to transform society but now armed with the power to achieve it. And a large number of innovative social movements – most notably Occupy – were now emerging to challenge capitalism from the ground up, fired by a politics echoing many of Corbyn’s preoccupations.

Corbyn encouraged some social movement activists to join the party. But as astute Corbyn sympathisers have pointed out, a social movement has aims and methods very different to that of a political party. The latter aims to win votes based on the policies it proposes and to then apply them in government. But the former seeks something more profound: to challenge established ways of thinking and help ordinary people re-imagine their political capacities so they can become active agents in their own liberation. Merging the two approaches into one organisation capable of entering government would be unprecedented.

Pro-Corbyn journalist Paul Mason nonetheless believes Labour can do this by becoming ‘a horizontal, consensus-based organisation, directly accountable to its mass of members’ – and indeed it must do this if Corbyn is to win power. The shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, argues that Labour needs to go even further once in government so as to unlock the peoples’ potential – especially as its radical economic programme will rely on the ‘active engagement on a daily basis between government and civil society and the real experts on the shop floor’.

But evidence that Labour has actually started to morph into a social movement is patchy. Momentum’s membership still represents less than 10% of Labour members. Local Momentum branches are working with the homeless, asylum seekers, women’s and youth groups as well as food banks. The political efficacy of such efforts, however, remains uncertain. In any case, the organisation has in the main focused on internal party matters: winning seats on the National Executive Committee (NEC) and ensuring the selection of approved candidates. In this it has enjoyed some success, recently winning all nine NEC seats voted for by members, although its slate won little more than half of votes cast. And, despite Momentum’s attempt to generate enthusiasm, over two-thirds of Labour members failed to vote. Perhaps even more surprisingly, earlier this year a similar proportion of Momentum members did not vote in elections for the organisation’s own governing body.

It is undoubted that most Labour members approve of Corbyn. But their failure to even click online in support of his favoured NEC candidates suggest few are prepared to assume the arduous obligations of being a member of a social movement – something which requires an intense involvement in local communities. This is possibly because most who recently joined Labour are largely mature former members who quit the party during the Kinnock and Blair years. They have a conventional view of political action. If they are the ones flocking to the Labour leader’s rallies and tweeting the hashtag #WeAreCorbyn, some see this as evidence more of a personality cult rather than of a social movement, many of which – like Occupy – are uncomfortable with the very concept of leadership.

The MP Clive Lewis tweeted recently about the party, saying: ‘The birthing of something new is… painful. But at the end of that process something with immense potential is created. It will wobble. It will stumble. But with the right care and support, it will thrive.’

It is arguably too early for us to see a fully transformed Labour Party. Perhaps the party’s Democracy Review will help it acquire the characteristics of a social movement: that is certainly the hope of many Corbynites.

An election is less than four years away. But Corbyn’s social movement is barely born. That means any government he leads will lack the kind of extra-parliamentary support the left has always considered necessary for the success of its transformative agenda. Lacking such support, therefore, a Corbyn government will ironically struggle to counter opposition from the City and business except through parliament – that is, just like every other Labour government that has come before.

Steven Fielding is a professor of political history at the University of Nottingham; this article also appears at theconversation.com.