For a few years at the height of the Sixties, the epicentre of cool was to be found between junctions 16 and 17 of the M1. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports on an unsung cultural landmark

If you wanted to be among the hip young things in 1967, your best bet wasn’t London hotspots like the Marquee, the Bag O’Nails, or the UFO, but was to be found 80 miles north of the capital, between junctions 16 and 17 of the M1.

Watford Gap Services, known as the Blue Boar, was Britain’s first motorway service station and a key stop-off point for gigging bands hacking it up and down the motorway between London and the North as the beat boom exploded.

As unlikely as it seems, those services at Watford Gap took on such mythical proportions that ‘when Hendrix first came to London’ – as Ronnie Wood later recalled – ‘he thought the Blue Boar was a club and wanted to know who was playing there that night’. In the early hours of the morning, the Blue Boar was a just as much a culturally significant space as the trendy London venues and a rare place where strange creatures with long hair and eastern-inspired fashions could be spotted in the wild.

Those who genuinely remember the 1960s describe the Blue Boar at that key time vividly. It was a place where ‘the counterculture met the straight culture,’ confirmed influential folk rocker Roy Harper, and ‘crushed velvet trousers outnumbered truckers’ overalls’ at the service station’s cafeteria, according to Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason. Chris White of The Zombies, who played hundreds of UK gigs in the years following the success of their 1964 classic single She’s Not There, said: ‘Lines of musicians would queue up for their hot food before climbing back into ailing vans full of guitars. It was the feeding trough of the mid-60s Beat Boom.’

The Blue Boar was a literal staging post on the road to success, and its significance went far beyond being a place to grab a fry-up and a cup of tea. When a 19-year-old Keith Richards was captured on camera by photographer Philip Townsend, sitting at the cafeteria counter in July 1963, looking like a rabbit in the headlights, the Rolling Stones were just one more adolescent band trying to make it. On that occasion, they were on their way to Birmingham to film their first television appearance, performing their debut single, Come On. The rest is history. Future Stone, Ronnie Wood, recalled that the Blue Boar had ‘the most wished-on jukebox in England because every musician who ever went there wished that he would one day hear his latest song being played on it when he walked in’.

The venue’s affinity with rock and roll is not such a stretch of the imagination. This was an age when the service station connoted a dazzling modernity – with not a little sense of the open road of rock’s foundational Americana – rather than quotidian functionality.

In the early years of the motorway era, services were destinations in themselves, where visitors could buy postcard views and watch the traffic from chrome-bedecked restaurants that straddled the carriageways. As Joe Moran points out in his cultural history of the motorway, On Roads (2009), 24-hour service was previously alien to Britain, and the service station was as close to the cinematic glamour of the American diner as its still war-fatigued patrons had ever seen.

Admittedly, the Blue Boar didn’t initially live up to this promise of futuristic excitement. The first customers were served in wooden sheds as it wasn’t completed in time for the 1959 opening of the M1. The finished building, the work of Harry Weedon (the man behind the Odeon’s scores of interwar Art Deco cinemas) and modernist architect Owen Williams, was condemned by the Architects’ Journal as a ‘commonplace design’ at a time of mid-century modernist innovation.

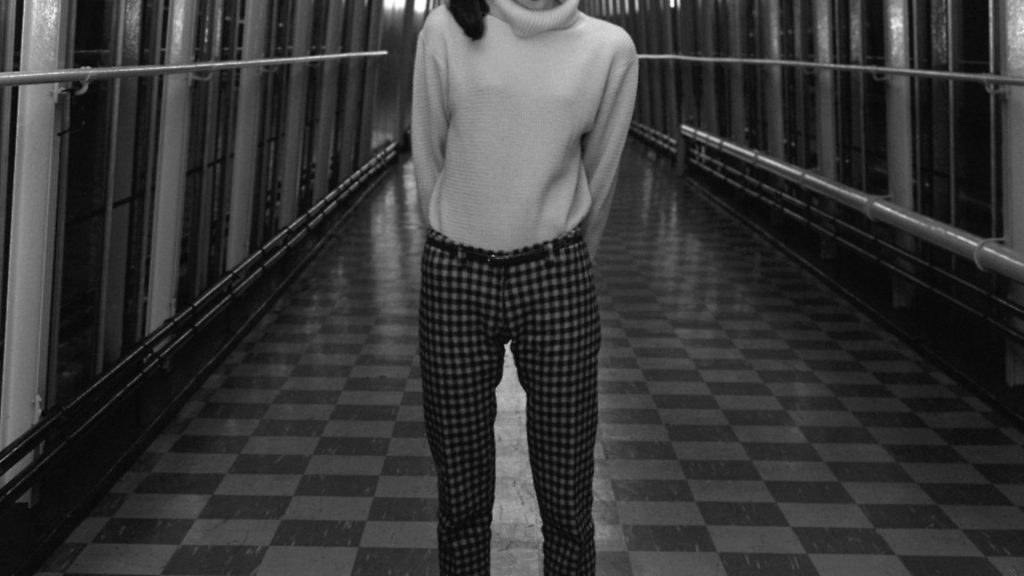

Even so, that the Blue Boar had some architectural panache is evident in David Redfern’s photograph of Sandie Shaw standing characteristically barefoot on the building’s chequered lino, framed by the modishly angular steel of one of the interior corridors.

Shaw was of course Eurovision Song Contest-winner in 1967, arguably the most important year in British music history, when Hendrix came to London and set fire to his guitar, Jagger and Richards got their drug convictions, and All You Need Is Love and Waterloo Sunset sound-tracked the year. The Blue Boar had been spruced up and upgraded to waitress service in 1964 and was in its heyday as it hosted the bands that emerged that year.

Pink Floyd’s gig total for 1967 topped 200 as August’s debut LP The Piper at the Gates of Dawn put them at the forefront of the psychedelic revolution. Nick Mason made the realities of the Floyd’s motorway-centric life clear in his rock memoir Inside Out (2004) – constantly criss-crossing the country and with no money for hotels, they frequently drove through the night, and ‘it felt as though we were permanently in the van’, he writes.

Fortunately, they had swapped their knackered 20 quid Bedford for a new Ford Transit following their EMI signing, but even so, when they ventured north for the first time to play Leeds’ Queen’s Hall on the Friday night of February 3, 1967, the M1’s extension between Rugby and Leeds wasn’t yet finished, leaving them to chug up the A roads. The sustenance and camaraderie of the Blue Boar provided the same welcome relief as the fast, smooth motorways.

Despite the prohibition on service stations applying for alcohol licences, visits to the Blue Boar didn’t preclude rock and roll thrills, and even occasional sex and violence. On a BBC radio documentary about the Blue Boar, Francis Rossi of Status Quo, who recorded Pictures of Matchstick Men in 1967, recalled groupies targeting the service station just as much as they did dressing rooms and hotels.

Ronnie Wood, a member of the Jeff Beck Group in 1967 – the year of the band’s formation and of four nationwide tours, venturing as far north as the Scottish Borders via the M1 – recalled in his 2007 memoir that he and Beck were once menaced by tyre iron-wielding rockers as they were eating in the Blue Boar’s cafeteria and had to abandon their meals and make a dash across the forecourt to avoid a beating.

By the 1970s the service station era was over. The frills and the waitresses vanished and the food became the butt of many a joke as Egon Ronay excoriated it in his Daily Telegraph reviews.

Roy Harper had turned against the Blue Boar in particular by 1977, its glory days then well and truly over, with his song Watford Gap decrying it as a ‘A plate of grease and a load of crap’. The Kinks’ 1972 album track Motorway had expressed much the same sentiment.

By the 1980s, the image of the service station was miserable enough to be of interest to one Steven Morrissey. Joe Moran explains the Smiths’ frontman’s interest in service stations, evidenced by 1986 B-side Is It Really So Strange? (its protagonist travels up and down the M1 and loses his bag at Newport Pagnell services), pointing out that ‘Like the out-of-season seaside resorts and rainy northern towns he also chronicles in his songs, they mine a rich seam of English ordinariness and gone-to-seed glamour’. But back in the 1960s, the service station was nothing so doleful, and was as symbolic of youthful, forward-looking hopefulness as the era-defining bands who fuelled themselves there. As such, the Blue Boar should be considered as much a part of the quasi-mythical landscape of 1960s Britain as the Kinks’ Waterloo Station or the Beatles’ Penny Lane.