Elvis Presley did much to promote Hawaii’s musical culture, but its native sons have far more to offer themselves. SOPHIE DEBOICK reports.

Honolulu is more than 2,000 miles from the West Coast of the US, but is a place deeply embedded in American mythology. As a tourist playground focussed on Waikiki – once the home of the royal court of the founder of the Kingdom of Hawaii, Kamehameha I – Honolulu looms large in the popular imagination as a pristine paradise. As leisure and musical entertainment go hand in hand, this economic and political capital of the 137 Hawaiian islands has also been the musical capital, but Honolulu’s centrality to the history of Hawaiian music goes back further than Hawaii’s relatively recent tourist era, to intrepid voyagers, grasping colonialists, and a deposed queen.

After Captain Cook ‘discovered’ the Island of Hawaii in 1778 and was killed the following year after his kidnapping of King Kalani’opu’u didn’t go down too well, a familiar story of asset stripping followed as more visitors from the Old World came in Cook’s wake. But the coming of the Europeans was crucial for the music of the islands, as the ancient mele chant of the hula dance rituals became influenced by the songs that the missionaries and would-be colonialists brought in their hearts and the instruments they held in their hands.

The Portuguese four-stringed cavaquinho, or more specifically the Madeiran variant, the smaller braguinha, was the inspiration for the Hawaiian ukulele (meaning ‘jumping flea’), which, along with the steel guitar that would be developed on the islands, would define the sound of Hawaii.

Queen Lili’uokalani, who ascended to the throne in 1891, is a legendary figure in the musical heritage of Hawaii. Lili’uokalani and her three siblings, known as Na Lani ‘Eha (the Royal Four), were all accomplished musicians, and their songs form the backbone of Hawaiian musical history. Lili’uokalani’s Aloha Oe (Farewell to Thee) is as much a cultural symbol of Hawaii as the national anthem she wrote (He Mele Lahui Hawai’i). Conceived, so legend has it, when Lili’uokalani was returning to Honolulu on horseback after a visit to military official James Harbottle Boyd in 1877, it was written at the royal palace of Washington Place in the city. A power struggle with the island’s plantation owners resulted in the overthrow of the Queen, with US support, in 1893, the prelude to Hawaii becoming a US territory in 1898, but her influence on Hawaiian nationhood could not be so easily removed.

Early the next century, Charles E. King and John Kameaaloha Almeida would vie with each other for the title of ‘Dean of Hawaiian Music’. King, born in Honolulu in 1874 of part Hawaiian ancestry, and later to become a member of the islands’ senate, wrote Ke Kali Nei Au in 1926. Adapted as Hawaiian Wedding Song, it would be a hit for Andy Williams in 1958 and become a crooners’ standard. Blind multi-instrumentalist Almeida was born in Honolulu County in 1897, became a radio star in the 1930s, composed hundreds of songs and was later the musical director of Honolulu’s 49th State Hawaii Record Company (the name anticipated Hawaii’s accession to the Union in 1959, but did not bargain for Alaska acceding first, and Hawaii in fact becoming the 50th state).

By the time King and Almeida were finding success, Honolulu’s future as the locus of the Hawaiian tourist industry could be glimpsed. From 1935, the city was promoted as a paradise destination by the Hawaii Calls radio show, broadcast live from the courtyard of the Moana Hotel on Waikiki Beach every week for the next 40 years.

The show gave a platform to Hawaiian performers, including Almeida, making them famous on the mainland US. Each broadcast began with the sound of the waves lapping on the beach, and such island fantasies were suddenly in reach when a daily flight service to Honolulu from San Francisco began in 1936 (albeit with a $360 one-way price tag and a 21-hour flight time). The attack on Pearl Harbour of December 1941 arrested the development of the nascent Hawaiian tourist trade, but it entered a golden era in the 1950s.

Hawaii Calls was characterised by ‘hapa haole’ (literally ‘half white’) songs in the 1950s, as the influence of Western popular music bit hard. Stereotypical imagery abounded – Honolulu’s Alfred Apaka sang of ‘A little brown gal in a little grass skirt/ In a little grass shack in Hawaii’ (Little Brown Gal [1950]), while the queen of the traditional yodelling ‘ha’i’ falsetto, Haleloke Kahauolopua, exclaimed ‘There’s no Christian Dior on this tropical isle/ For each wahini likes to set her own style/ Just a little grass skirt and a very big smile’ (Easter in Waikiki [1953]).

The building of luxury hotels like the Hawaiian Village – opened in 1955 and the birthplace of that symbol of plastic ‘Hawaiicana’, the Blue Hawaii cocktail – and the arrival of airliners at Honolulu Airport in 1959 marked the coming of age of Hawaiian tourism. For the islands’ musicians, this meant plenty of work in the bars and hotel showrooms, but in the 1960s local musicians began to look to traditional sounds rather than playing the songs about grass skirts the tourists craved.

Formed in Honolulu in 1960, the Sons of Hawaii were one of the bands who pioneered an authentic Hawaiian ‘country’ music.

Under the leadership of ukulele virtuoso Eddie Kamae and slack-key guitar master Gabby Pahinui, the steel guitar was restored to the heart of Hawaiian music. The band played their first gig at the Sandbox club on Honolulu’s Sand Island Access Road in 1960. In 1969 ukulele player Moe Keale joined the band. He would later become known in the US as a regular star of Hawaii Five-O, becoming a familiar face to US audiences much like Honolulu-born singer and TV star Don Ho. Ho, resident performer at Duke Kahanamoku’s club at Waikiki International Market Place, saw his pop ballad Tiny Bubbles (1966) become a Billboard hit, and proved that hapa haole endured even as the Hawaiian musical renaissance grew.

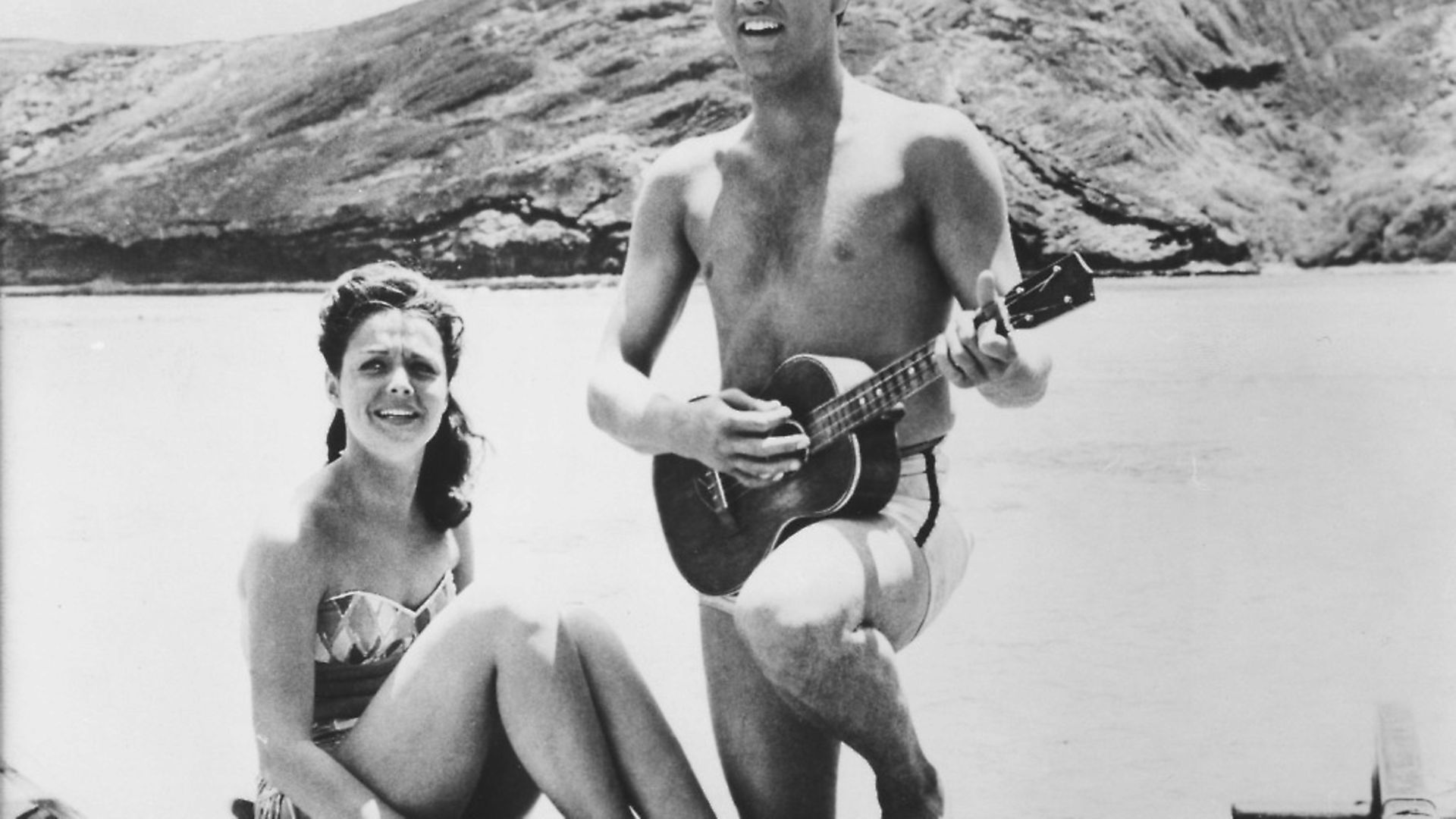

Elvis managed to both keep the stereotypical image of Hawaiian culture alive, while paying genuine tribute to a place he loved. In early 1961, he played a benefit concert for the USS Arizona memorial (it was one of only two ships lost completely at Pearl Harbour), and began filming Blue Hawaii (1961) in and around Honolulu, the first of three films he made on the island, all of them depending heavily on imagery of palm trees and pristine beaches.

While the title song was originally from Bing Crosby’s Waikiki Wedding (1937), it was joined by covers of both Charles E. King’s Hawaiian Wedding Song and Queen Lili’uokalani’s Aloha ‘Oe. And while his 1973 Aloha from Hawaii – the first live worldwide concert broadcast – like the USS Arizona benefit had been conceived by Elvis’ manager as a publicity winner, Elvis turned it into a tribute a much-loved Hawaiian songwriter, Kui Lee, who had died of cancer in 1966, aged just 34. He covered Lee’s I’ll Remember You during the show, and donated the proceeds from the concert to the fund set up in his name.

By the time of Aloha from Hawaii, an indigenous rights movement that went hand in hand with the rediscovery of Hawaiian culture was well in train. Gabby Pahinui became a figurehead of this rediscovery and a guiding light for the artist who represents Hawaiian music today for many.

Born in Honolulu in 1959, Israel Kamakawiwo’ole was the nephew of Moe Keale and steeped in the musical life of the islands. He formed the Makaha Sons of Ni’ihau with his brother Skippy in 1976 and became a vocal advocate for Hawaiian independence, the band covering Mickey Ioane’s Hawai’i 78, about the clash between land rights demonstrators and the National Guard at Hilo Airport of that year.

Kamakawiwo’ole opened his second solo album, Facing Future (1993) with his own heartfelt version of Hawai’i 78, but it was not that song that made it the biggest-selling album by a Hawaiian artist of all time. Back in 1988, Kamakawiwo’ole had made a spur of the moment demo tape at an early-hours recording session at the Audio Resource studio run by engineer Milan Bertosa at the downtown high rise, the Century Center.

In just one take he recorded a medley of Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World that took considerable liberties with the original arrangements, but captured a moment of alchemic inspiration and a purity of voice that led Milan Bertosa, again on engineering duty for the recording of Facing Future at Honolulu’s Mountain Apple studios, to dig out the demo and suggest it went on the album in unexpurgated form. And so it appeared, complete with Kamakawiwo’ole’s tribute to musical forefather, Gabby Pahinui – ‘This one’s for Gabby’ – at the beginning.

This off the cuff recording has gone on to global fame. Used over the end credits of the Brad Pitt vehicle Meet Joe Black (1998), the song has since become ubiquitous on film and adverts, and it has vied with the original Wizard of Oz arrangement, as the rainbow has become a global symbol of hope amid the pandemic, and the song has been embraced anew. Kamakawiwo’ole died aged just 38 the year before his song became famous, but as his childhood friend and fellow musician Del Beazley has suggested, his mana (spirit) lives on in a song that, in its yearning for a place of paradise, echoes the dreams of many a traveller to Honolulu, and in its fragile hope is fitting to our times.