While the US produced a very raunchy scandal, British pop’s great controversy was a little more tame.

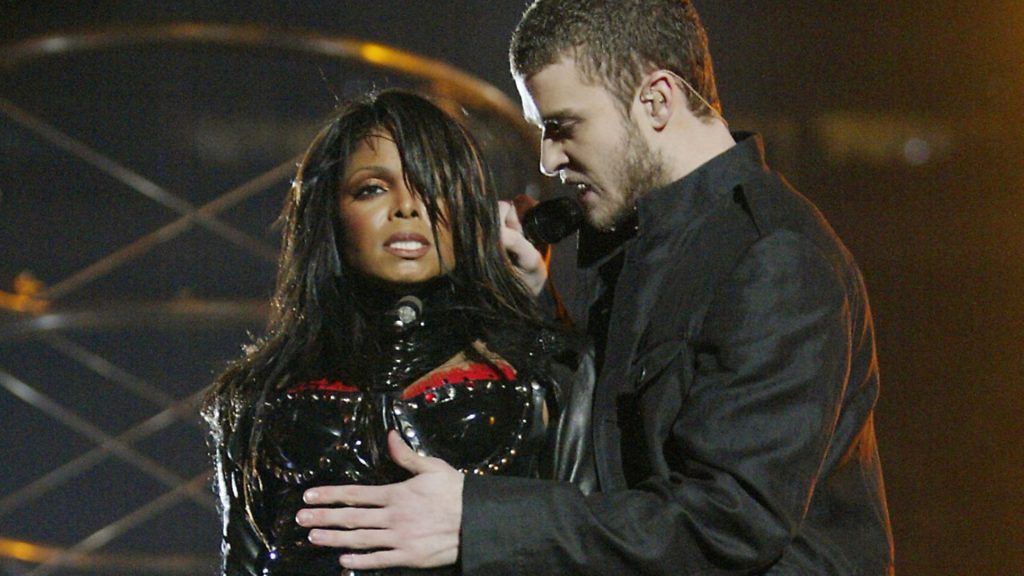

Lewdness was in in 2004. As Justin Timberlake tore off part of Janet Jackson’s bustier at the Super Bowl XXXVIII half-time show on the climatic line ‘I’m gonna have you naked by the end of this song’, ‘nipplegate’ and ‘wardrobe malfunction’ entered the lexicon.

The second best-selling single of the year was Eamon’s expletive-laced proof that chivalry is dead, F**k It (I Don’t Want You Back), while the response from his ex, Frankee, F.U.R.B. (F**k You Right Back), dealt a double blow in detailing Eamon’s alleged sexual inadequacies and knocking his single off the UK top spot. Kelis’ euphemistic Milkshake, OutKast’s simultaneously wholly novel and inherently retro Hey Ya! (famously rhyming ‘mama’ and ‘cumma’ in a couplet the radio sensors seemed to miss) and Britney Spears’ smouldering Toxic, all had uninhibitedly sexy videos, although the aerobics-themed one for Eric Prydz’s Steve Winwood-sampling Call On Me took the biscuit for pop porn (in an interview that year, PM Tony Blair confessed to watching the music channels while exercising, and said of the Prydz promo ‘The first time it came on, I nearly fell off my rowing machine’.)

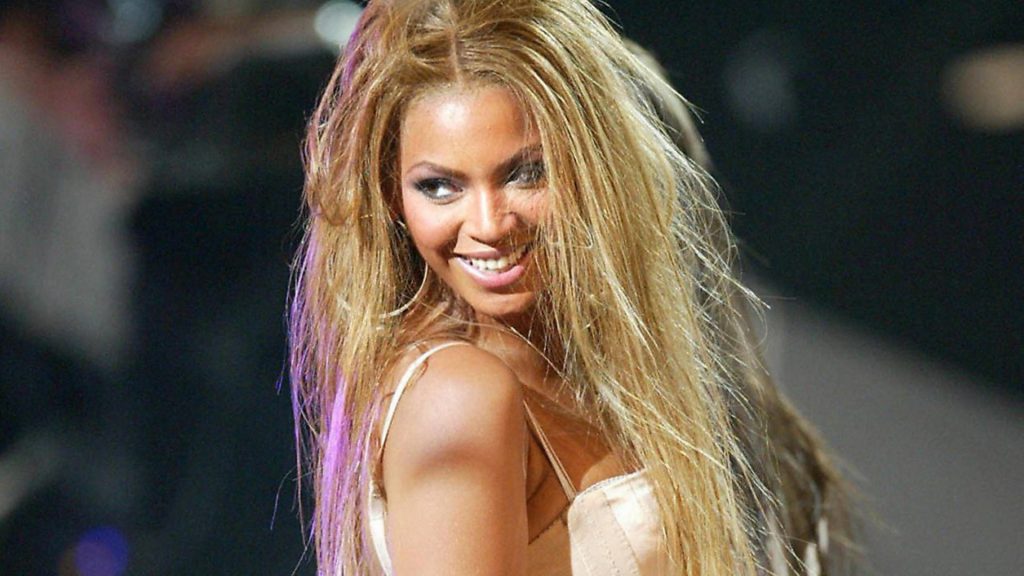

Meanwhile, the Scissor Sisters told us to Take Your Mama, The Streets said Dry Your Eyes, and Band Aid 20 asked Do They Know It’s Christmas? again. Peter Andre’s career got a shot in the arm via I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! and the televising of his burgeoning romance with Katie Price, and his Mysterious Girl topped the chart on its re-release. Two mega-stars were born, as Kanye West got universal critical acclaim for debut LP The College Dropout and, having already made a claim to individual stardom with Crazy in Love the previous year, the wrapping up of Destiny’s Child via the release of their final album marked Beyoncé’s true emergence as a solo artist. But it was also a year of notable endings amid seismic changes in the way music was consumed, as well as one of a certain British reserve.

A diverse roster of artists bowed out in 2004, whether existentially or professionally. George Michael’s LP Patience was announced as his last physical release, with future material to be available download-only for a donation to charity. This move, and the fact that the album contained the notorious skewering of the Bush-Blair relationship, Shoot the Dog, proved Michael was still the music industry’s foremost non-conformist, if not rebel.

The LP would turn out to be his final album of original material before his sudden death 12 years later. Johnny Cash’s death in late 2003 was followed by a final, posthumous release – his 89th LP, My Mother’s Hymn Book. The sparse, acoustic recordings had been made a decade before, but the focus on the southern spirituals that had echoed around the rural New Deal project home Cash grew up in, with ‘the life beyond’ their sole topic, gained incredible poignancy following his death.

Pavarotti, then pushing 70, gave his last performance in an opera in mid-March, appearing in Tosca in New York. (He would perform, later, at the opening of the 2006 Turin Winter Olympics). Meanwhile, an unplanned departure from the limelight came for David Bowie when, eight months into the triumphant A Reality Tour, he had what turned out to be a heart attack onstage in Prague, collapsing after a performance in Germany two days later. While a handful of live appearances and two genius albums followed, 2004 marked the beginning of the end.

The death of Ray Charles in June was quickly followed by the October release of the biopic that made Jamie Foxx an instant star and an Oscar-winner. Other notable demises of the year ranged from Wu-Tang Clan’s Ol’ Dirty Bastard to Sacha Distel and multi-million single-selling Mud frontman Les Gray. The composer who sound-tracked over four decades of Hollywood blockbusters, Jerry Goldsmith, and the taste-shaper of British music, John Peel, joined the list. But most dramatic was the on-stage murder of ex-Pantera guitarist Dimebag Darrell, killed along with three others by a gunman at a gig in Ohio in December.

An ending came for another icon of music that year – Our Price. After being sold to various parties in an effort to save it, all the business’s branches had been closed by April 2004, and many Brits had cause to reminisce about teenage Saturday afternoons spent stalking the racks during the brand’s heyday. Founded in 1971 as Tape Revolution, when it focussed on selling new-fangled cassettes and eight-tracks, it rebranded as Our Price Records on the eve of punk in 1976. Floated on the stock exchange in 1984 and acquired by WH Smith two years later, the 1980s were Our Price’s glory days, and it had more than 300 stores by 1993. But the launch of the UK Singles Downloads Chart on September 1, 2004 showed that the way music was bought was changing irrevocably.

The PR opportunity of being the first No.1 on the new chart saw Sugababes, Muse, Faithless, Goldie Lookin’ Chain and Snow Patrol all strategically release singles the week before, but it was Westlife, with a re-release of 1999’s Flying Without Wings, that claimed the title. While there was a certain revitalisation of the industry via downloads, with the iTunes Music Store celebrating 70 million downloads on its first anniversary in April, and launching in the UK, France, and Germany in mid-June, the digital music revolution sounded the death-knell for the record shop.

Even if one of the biggest names in British music retail was failing, British music was still riding high, with something bordering on easy listening proving wildly popular. Dido’s Life for Rent and Katie Melua’s debut LP, both released in late 2003, continued to dominate the album charts and were as far from the spectacle of Janet Jackson’s nipple and the sex-obsessed offerings emerging from the US as could be imagined.

With Coldplay on hiatus, boarding school boys Keane took up the mantle for piano-led, middle-class earnestness, seeing their debut LP, Hopes and Fears, ricochet back to the No.1 spot twice after topping the chart on its May release. Their soaring yet genteel expressions of existential angst Everybody’s Changing and Somewhere Only We Know were inescapable that year. While making claims to pop-punk spikiness, Busted and their protégés McFly in fact harked back to more innocent times of the rock ‘n’ roll boy band, and McFly’s LP Room On The 3rd Floor debuted at No.1, breaking The Beatles’ record as the youngest group ever to do so. Not all was anodyne in British music, however, and more in-your-face offerings came via Franz Ferdinand’s eponymous debut of February and top 3 single Take Me Out, Razorlight’s June debut Up All Night, and The Libertines’ self-titled second album, released in August.

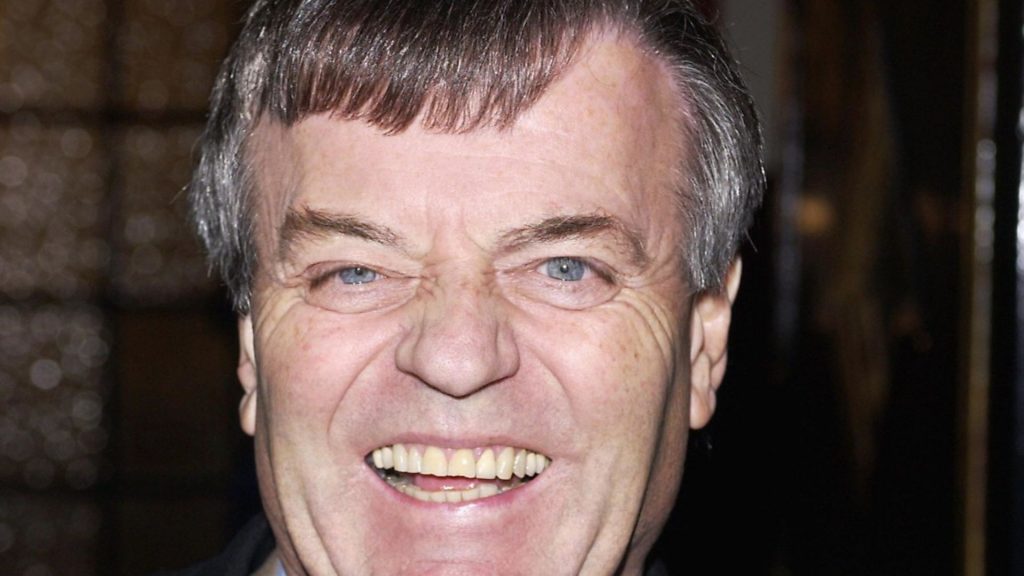

But the scandal of the year in the British music world remained an endearingly low-key one, as Tony Blackburn was suspended from his job on Classic Gold Digital’s breakfast show for playing Cliff Richard records. In a scenario straight out of Alan Partridge, live on air on the morning of Wednesday June 23, Blackburn read out an email sent to him by the head of programmes declaring that ‘we have a policy decision that he doesn’t match our brand values’, before theatrically ripping it up and defiantly playing We Don’t Talk Any More and Livin’ Doll back to back.

Blackburn’s suspension provoked an outcry, with leader of the Commons Peter Hain responding to a request for a debate about the cost of digital downloads with: ‘May I just say that I hope that Cliff Richard’s songs will feature prominently in any downloading of music from the internet? [I am] right behind Tony Blackburn in his choice of music.’ The short-lived scandal is thus forever immortalised in Hansard.

That the digital music revolution was well under way was clear as ‘podcast’ made its first appearance in print, but the debuts of the phrases ‘social media’ and ‘pay wall’, along with the launch of Facebook in February, also suggested huge changes in the way information was spread and consumed.

Facebook would later play a crucial role in issues that were still emerging in world politics in 2004. The re-election of George W Bush in November seemed the nadir for American politics, while the brutality of the Chechen conflict, including September’s Beslan school massacre, and Ukraine’s Orange Revolution were precursors to a new era of Russian aggression.

Social media, incompetent US leadership and an emboldened Russia have all come together in the disaster of today, and while the largest EU expansion to date, with the admission of 10 countries on May 1, 2004, meant the European project looked unassailable then, that has not turned out to be the case.

The Madrid train bombings, exposure of the Abu Ghraib atrocities and declassification of the US ‘Torture Memos’ made 2004 a year of global turmoil when the world felt less safe than ever. But it did not feel as unsafe as today, and while the pop juggernaut that never stops provided relief then, music feels like a rare source of salvation now.