Avant-Garde Artist Natalia Goncharova was an Exponent of ‘everythingism’, producing work that spanned techniques and styles. Claudia Pritchard reports on an exhibition that reflects her dazzling varied output.

“I am by no means European,” declared the Russia-born artist Natalia Goncharova as she pursued her studies in Moscow at the beginning of the 20th century, just as the eyes of the art world, and importantly for artists, of the collectors, was on France. Cézanne, Gauguin, Picasso – these were the names on everyone’s lips.

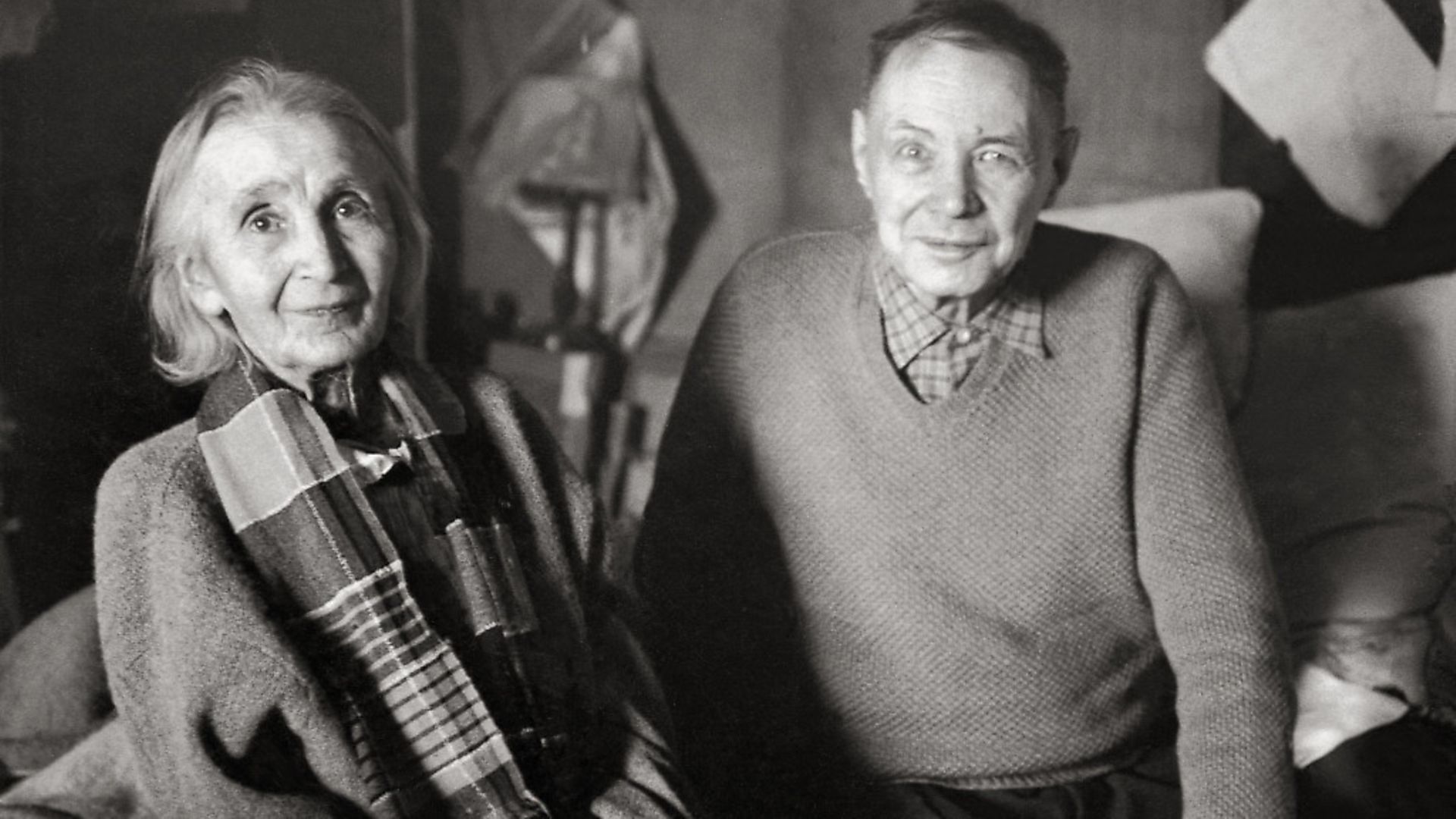

Goncharova’s precocious work, too, was being viewed with interest. But at the moment when she could have done as so many other rising artists did and set out for Paris, to learn and to be noticed, in 1903 she headed instead with her life partner Mikhail Larionov for the Crimean peninsula, absorbing the local decorative arts, archaeology and culture.

Traditional Russia crafts and rural practices were to appear in her early work, as a new exhibition, Natalia Goncharova, at Tate Modern illustrates.

Washing textiles, picking fruit… these are the everyday subjects in her early painting. Like a novice author advised to write about what they know, she was depicting familiar subjects.

Natalia Goncharova was born in the western Russian province of Tula in 1881, the same year as Larionov, Picasso and Fernand Léger. Her family, initially wealthy through their textile business, moved to Moscow as their fortune dwindled, and the country girl quickly became a young woman of the city, while lamenting her detachment from the natural world. Irrepressible flower motifs would often creep into her work, however industrial its subject.

Prolific and totally free-range in her choice of subjects, in 1913 she was the subject of a massive monographic exhibition in Moscow. Bright still-lifes, dour street scenes and sombre portraits were among the 800 works on show, alongside attractive theatre, textile and fashion designs and religious works which combined traditional elements with modern motifs, and which, in accordance with respectful practice, were shown in a room of their own.

A few weeks before the opening, Goncharova and other artists paraded through the city streets with hieroglyphic patterns painted on their faces. Journalists had been tipped off in advance, so the streets were lined with curious crowds and photographers keen to find out more.

The publicity stunt worked. Thirty-one works were sold, the catalogue was reprinted twice, and the six rooms stacked high with artworks at the Mikhailova Art Salon were viewed by 12,000 people in five weeks.

Goncharova might protest that she was not European, and would incorporate Russian traditions secular and sacred into her work for decades, but in fact European influences were strong.

She and Larionov were particularly influenced by the Italian Futurist movement, with its emphasis on a new order, its startling manifesto rejecting the past, and its dynamic depictions of movement in both painting and sculpture.

Together they forged a new style, rayonism, that broke figurative images into shards of light. And it was her embrace of so many mediums and movements and her enthusiasm for other art forms that prompted a new art term to describe her style: vsechestvo, or ‘everythingism’.

At the time of her huge 1913 Moscow show, Goncharova had sped through several styles, reached her own futurist vision, with restless machinery whirring and grinding in perpetual motion in Loom + Woman (The Weaver, 1912-13) and Dynamo Machine (1913).

But for all her earlier protestations of a non-European stance, by 1914 Goncharova could no longer resist the lure of Paris, and after a first visit to work on a commission, she moved there with Larionov in 1916, settling permanently in 1919 in an apartment on the Rive Gauche, on the corner of rue Jacques-Callot and the rue de Seine.

Here she lived with Larionov, whom she eventually married in 1955, until her death at home in 1962. The marriage, after more than 50 years together, was prompted by concerns over the future of each artist’s legacy. In 1950 Larionov had had a stroke in London, where Goncharova had built up a considerable following, notably through her designs for ballet.

It was the pivotal 1913 Moscow show, which is re-created in part at Tate Modern, that began a lasting relationship with the world of dance. The impresario Sergei Diaghilev immediately asked her to design the backdrop and costume for a new version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera-ballet Le Coq d’Or.

Drawing on traditional Russian folk art and costume, she created elaborate and opulent designs that confirmed western expectations of Russian exoticism, and the commission led to many others.

Touring with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes to Bilbao, Burgos, Seville, Avila and Madrid in 1916, and creating new designs and costumes for Spanish-themed ballets, Goncharova developed a passion for Spain, and especially for painting Spanish women. In these works she combines solemn portraiture with her interests in fashion and in the challenge of depicting movement.

In 1921 she contributed 46 works to the Russian Arts Exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, most of them theatrical designs, and in 1926 Stravinsky’s The Firebird with her set and costumes was given its London premiere at the Lyceum Theatre, to great acclaim. Nearly 30 years later the designs were revived for London and Edinburgh, introducing Goncharova to a whole new generation.

But despite her long tenure in fine art and design, the artist is only now receiving her first major British show. Many of the 160 or so loans rarely travel, including those from Russian’s State Tretyakov Gallery, which has the largest holding in the world of Goncharova’s work, and which led the way by buying three works from the 1913 exhibition.

From the start of her career, he work was spotted and bought by private collectors. After the October Revolution of 1917, many of such collections became state property. From 1919, the new Museum of Painterly Culture (MPC), charged with encouraging contemporary art and with Wassily Kandinsky in charge, bought seven pieces by Goncharova.

By 1924, the MPC was subsumed into the Tretyakov. While Goncharova’s work was appreciated in the aftermath of the revolution, in the Stalinist era, a move towards the ‘unification’ of art favoured pure realism. Purchasing for the state more radical art, especially by artists now living abroad, was banned.

Britain’s own collection is relatively small: Tate’s own Linen (1913), which shows the household laundry in a dynamic and futurist way, is joined by the The Forest from the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and Loom + Woman from the National Museum of Wales.

Counterweight to Goncharova’s forays into the performing world is her religious art, painted before the Soviet era, in some ways no less theatrical in its sumptuousness, but powerful and dignified. Her four Evangelists, solemn-faced saints with long scrolls, were considered by some the best work in the 1913 show. She had enormous respect and affection for the inexpensive prints called luboks that decorated homes at little cost, and produced her own series on both religious and secular subjects.

Equally at home with avant-garde writers, composers and fashion designers, as a book illustrator she was in her element with the ‘transrational’ poetry of Aleksei Kruchyonykh and Velimir Khlebnikov, which is intoned in one room of the Tate show.

Goncharova used collage to illustrate their poetry book Mirkontsa, the title of which translates as ‘world backwards’. And Goncharova, too, went back on her earlier declaration. In 1938 she was granted French citizenship, becoming, after all, European.

Natalia Goncharova runs at Tate Modern (tate.org.uk) until September 8; then at the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Florence (palazzostrozzi.org) from September 28 to January 12, 2020; Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki (ateneum.fi) February 26 to May 24, 2020