The life of ballet legend Rudolf Nureyev reads like a novel. As JASON SOLOMONS reports, every amazing chapter is captured in a new documentary film.

Rudolf Nureyev wasn’t just Lord of the Dance. He was an icon and a symbol on which the political and the cultural collided spectacularly. As the Cold War escalated, the Russians knew they couldn’t lay claim to the best refrigerators or cars, but they did have the best ballet, in the Kirov and the Bolshoi. In 1961, they of course claimed the first victory in the space race, too, with Yuri Gagarin’s orbit making him a Russian hero and a world figure.

Two months later, however, the West got a lucky break. While on a propaganda tour to Paris to promote Russia’s ballet supremacy, Nureyev defected. Retold with mounting excitement in a new documentary – Nureyev – his refusal to get on the Aeroflot jet back to Moscow and instead leap into the arms of the gendarmes at Le Bourget airport was seen as a crushing PR disaster for the Soviets, a blow to morale and a national betrayal.

Naturally, the West trumpeted it as a huge victory, immediately seeing the value of having this brilliant artist dancing on their side. Perhaps it should be no surprise, one of those facts of history that makes blinding sense in hindsight, that barely two months later, the Berlin Wall was erected overnight.

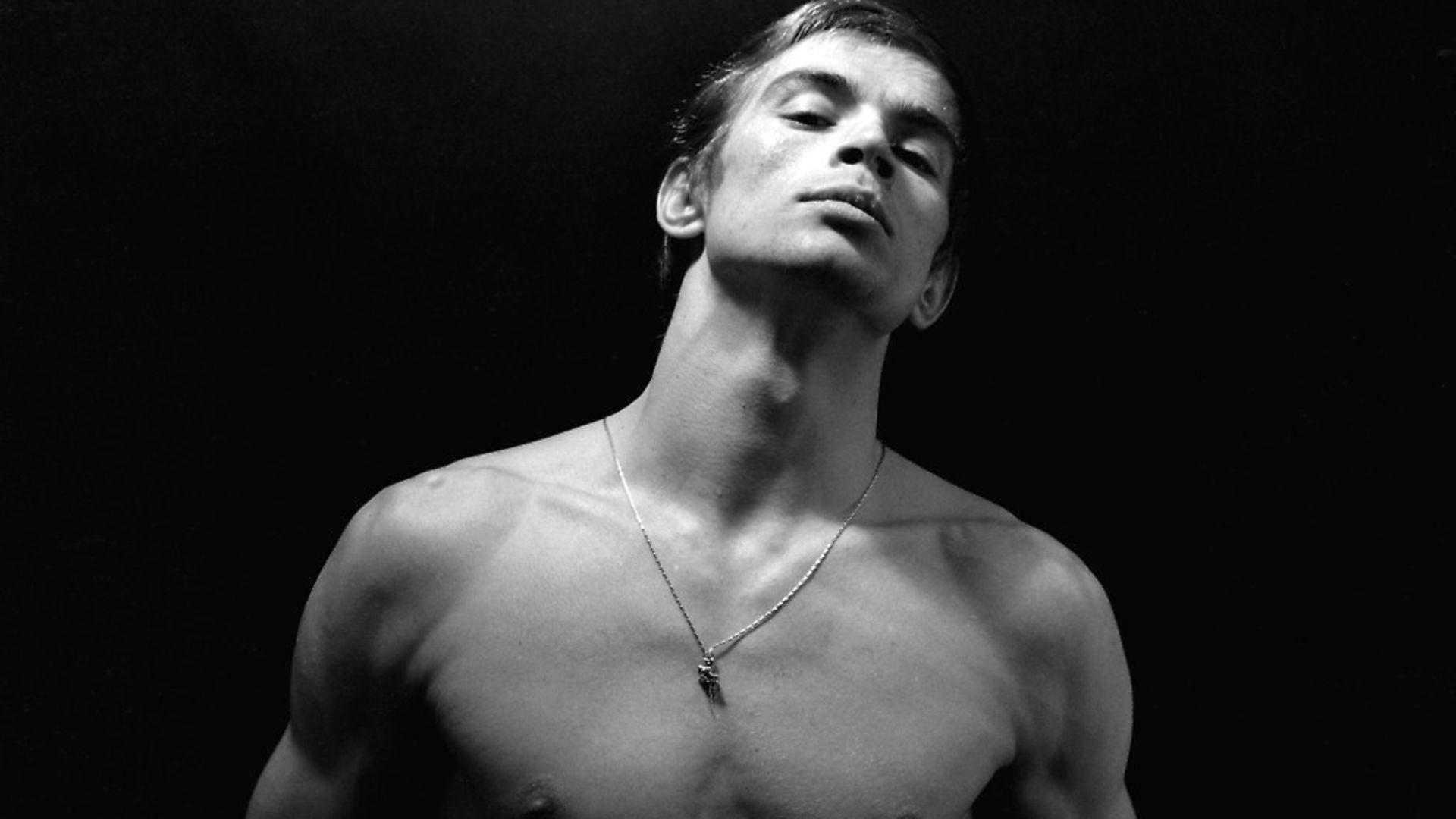

According to the film makers behind Nureyev, the dancer would probably have been able to leap even over that. ‘He was an unstoppable force,’ says co-director Jacqui Morris. ‘His eyes were a full laser beam of charisma and determination. Everyone we spoke to would refer to him as a ‘panther’ or ‘feral’ or a ‘beast’ or like something out of this world, like a ‘comet’. It was as if he was uncontainable.’

Her brother and co-director David Morris adds: ‘He was no respecter of national borders. Rules, barriers, conventions simply didn’t apply to him. He wasn’t exactly a rebel, just that if he saw something was in his way, he knew he could overcome it, conquer it.’

In his own words in the film (narrated by Dame Sian Phillips from his memoirs), Nureyev recalls he was trapped like a bird, ‘and a bird must fly’, which he certainly did, practically straight into Swan Lake in London with Dame Margot Fonteyn, a performance and a chemistry that became a classic of the arts.

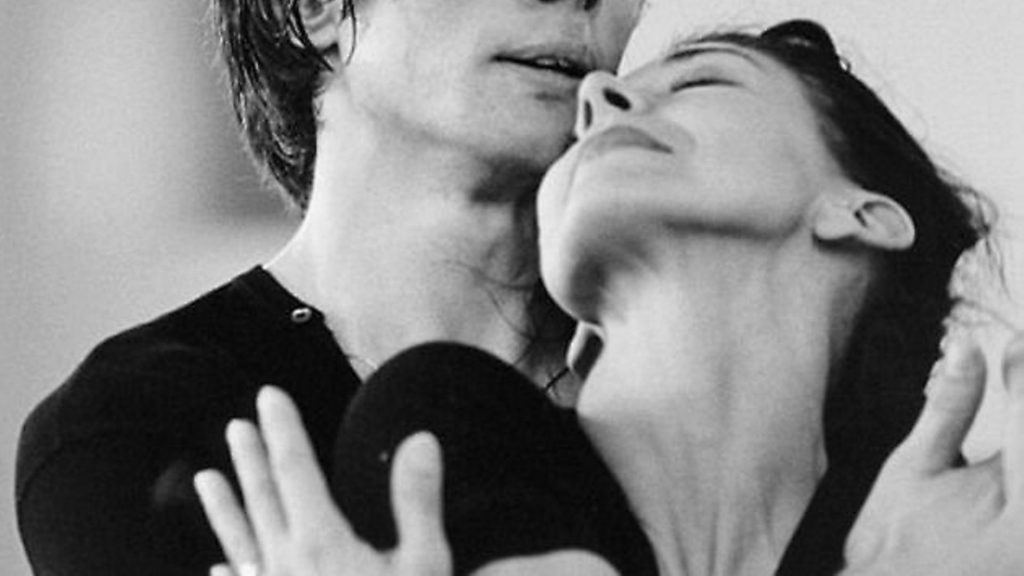

It was an unlikely partnership, this smouldering 22-year-old ball of controversy and a national pariah (‘an enemy of the people’ is the resonant phrase they used to call him) in his homeland, with a British grande dame and national treasure already approaching what was considered past her prime at 40. ‘She was the most beautiful little bird, exquisite,’ says Leslie Caron of Dame Margot.

I admit I wasn’t that familiar with the story of Nureyev, and this graceful yet fabulously entertaining new documentary filled in many gaps, but the legend of Nureyev and Fonteyn is part of 20th century cultural lore. I never saw them dance, of course, but hundreds of thousands of people did, huge crowds flocking to the Royal Ballet in Covent Garden.

‘To use a comparison to a contemporary phenomenon, he was as big as the Beatles, and that’s not over the top as a comparison,’ says David Morris. ‘It may not even be enough to describe it. There were screaming fans and rapturous receptions every night. People who’d never been near a ballet turned out in droves. It was suddenly a pop event – not Beatlemania, but Balletmania.’

Jacqui adds: ‘There were tales of as many as 40 curtain calls and encores every night. The musicians’ union began to complain because their members couldn’t get home and the overtime was proving very costly for the theatres.’

There’s a lovely bit of archive news footage in the film, showing the tiny post room at the Royal Opera House and dutiful clerks emptying huge sacks of yet more Nureyev fan mail until the letters pile up all over the floor. Like ballet itself, Fonteyn got an injection of new life as soon as she danced with Nureyev, as soon as he turned his full affection on to her. ‘Her elegance turned him from a lion into a panther,’ recalls the dance critic Clement Crisp in interviewed voiceover, ‘and she succumbed to this animalistic person before her.’

The clips of them dancing together are truly wonderful. Even a non-ballet fan can really see what all the fuss was about, so expressive, so sexy, so dramatic yet so sculpted and in harmony, their movement and expression the perfect reflection of the music, the embodiment of it, even. You can hear Nureyev’s own famous description: ‘We became one body, one soul, moving in one way; there were no divides, no gaps in age; we became the part.’

It must have been quite something to see them and the sheer number of performances they gave was staggering, not just in their base at the Royal Ballet in London, but touring like a rock band, to Milan, Paris, Denmark, Sweden, Zurich, the Netherlands, Israel, Australia and, finally, to New York and San Francisco.

Nigel Gosling was friend and landlord at the South Kensington house where Nureyev lived in the basement. In the film he recalls quite a bit of controversy that this Russian had just leapt to the front of the queue and swept Fonteyn away. ‘He had a devastating effect on the local population,’ quips Gosling. ‘Like the Great War, he wiped out a whole generation of British dancers.’ All anyone wanted to see was Nureyev.

The film would be nothing if it couldn’t show Nureyev and Fonteyn in motion, and thankfully there are some of their performances preserved. ‘But dance is ephemeral,’ says director David Morris. ‘It exists in one moment, then fades. Unlike a Picasso which you can see again, or Elvis whom you can hear on record, Nureyev really had to be witnessed in the moment, but thankfully we did discover plenty of film of him in action in order to convey the sheer electricity of watching the phenomenon dance. It was like an archaeological dig finding it though.’

Although prolifically gay, Nureyev was much sought after by illustrious and wealthy women, constantly invited to high society dinners in London, swanning in after those curtain calls and holding court. ‘He was quite the socialite, bit of a party animal and loved a drink. In turn, he’d invite these ladies to rehearsals and backstage and often allowed them to film him,’ says Jacqui Morris. ‘So we found lots of footage of him, sometimes a bit scratchy and often on the very end of VHS tapes, but very intimate, very lovingly capturing him in motion.’

Swan Lake is there, as is Giselle, Le Corsaire, a gorgeous Romeo and Juliet, both the balcony scene and, finally, the tremendously beautiful death scene, which accompanies the story of Fonteyn’s own decline, which left Nureyev heartbroken.

He went on to live in New York, in the Dakota Building no less, frequenting Studio 54 and – less known – the burgeoning gay ‘bathhouse’ scene. He danced with Martha Graham’s experimental modern company, and was there to welcome Mikhail Baryshnikov when he defected in 1974. They danced together at the White House, as if to rub Russian noses in it even further.

As the documentary shows, the trajectory of politics never leaves Nureyev. The thaw of Glasnost and a return to Russia; the arrival of AIDS; the lovers; the stint as director of the Paris Opera which saw him in charge and unleashing his temper and talent to almost single-handedly – well, with both feet – lift that venerable institution out of a slump and practically re-invigorate a whole city.

I love the chat-show appearances on Parkinson in the UK and The Dick Cavett Show in the US wearing the campest and most flamboyant outfits; and I loved the most glamorous mug shots ever, when Nureyev and Fonteyn were arrested in San Francisco in 1967, she in her fur coat, he glaring at the police camera. The pair had been caught up in a police raid targeting drug-taking ‘hippies’ in the Haight-Ashbury district. All charges against them were dropped.

Nureyev’s is a fascinating, short life – he died at just 54, having lived with AIDS for almost a decade while working in Paris – although it feels jam-packed. One interviewee recalls she can’t ever remember him sleeping.

‘You know when you discover your subject is born on the Trans-Siberian Express that you’ve got a good story, like the beginning of a great novel,’ says David Morris. They fill in the story of Nureyev’s first 20 years in Russia where no archive film exists by using some rather effective new dance tableaux scenes, choreographed by the award-winning dancer Russell Maliphant, both illustrating his harsh childhood in the peasant town of Ufa and his later student life in Leningrad, after he made the unlikely leap away from his soldier father, a man not very keen on learning that his son wanted to be a dancer.

Some of his friends, students and dancers from that period are also interviewed, and there’s a brilliant moment of one reunion that will have you in tears when Gorbachev eventually relents and allows this former ‘enemy of the people’, by now already one of the most famous Russian names in history, back home briefly in 1989.

‘He was like a little Napoleon,’ says David Morris. ‘He believed he could conquer anything, and he lived his life like a triumph of the will. He could be a monster to people he worked with, had a terrible temper which he attributed to his hot Tartar blood, and he had tragedies in his life – for example, he always missed his mother after leaving Russia. But he gave himself to dance. That was where he lived and breathed, where he was at home.’

For a feature doc about a ballet dancer, Nureyev is getting an impressive Europe-wide release, playing at 600 cinemas before appearing on DVD. Jacqui Morris says: ‘It’s because with all the dynamic dance footage, it’s a very cinematic experience, but also it’s because even in a short life, Nureyev seems to have touched everyone all over the world. Everywhere has memories of him, even if he danced there once, or just visited, it was a like a royal or papal visit. He touched whole cities with his charisma and it’s clear his legend dances on.’