Ray Kershaw travels to a city which has been through many reincarnations over the centuries, but none so dramatic or violent as its most recent

Early morning sunshine is unveiling one of Europe’s most beautiful squares. The cobbles bare of traffic, the scene would fit in any of the city’s many centuries; the handful of pedestrians perhaps direct descendants of the European peoples who lived, worked and died here, sometimes together, sometimes singly, during its first thousand years.

Yet all is not quite what it seems. And few, if any, of its present day inhabitants can trace their local lineage any farther back than 1945.

The square’s gloriously hotchpotch 15th-century town hall seems the ideal spot to solve a civic riddle: what do Vratislava, Wrotizla, Vraclaw, Wretslaw, Prezlav, Presslaw, Breslau and Wroclaw have in common? Polish historians may not agree but any schoolchild here can tell you: they’re all the same place.

Since its mysterious beginnings, the city has been always the capital of Silesia but its motherlands and fatherlands have come and gone like fickle parents, often changing its languages, always changing its name.

With its central European composite character, a cocktail pedigree of fluid nationalities, it’s been called a living microcosm of European history and candidate for the continent’s most European city.

Today it’s hard to imagine that the medieval market place of Europe’s Capital of Culture 2016 was once the devastated epicentre of one of Europe’s last but most seismic battles of the Second World War. Little remained of the 600,000 inhabitant city but a depopulated rubble field. German Breslau’s smoking ruins also had a new language, a new nationality and a new government. Its name was now Wroclaw.

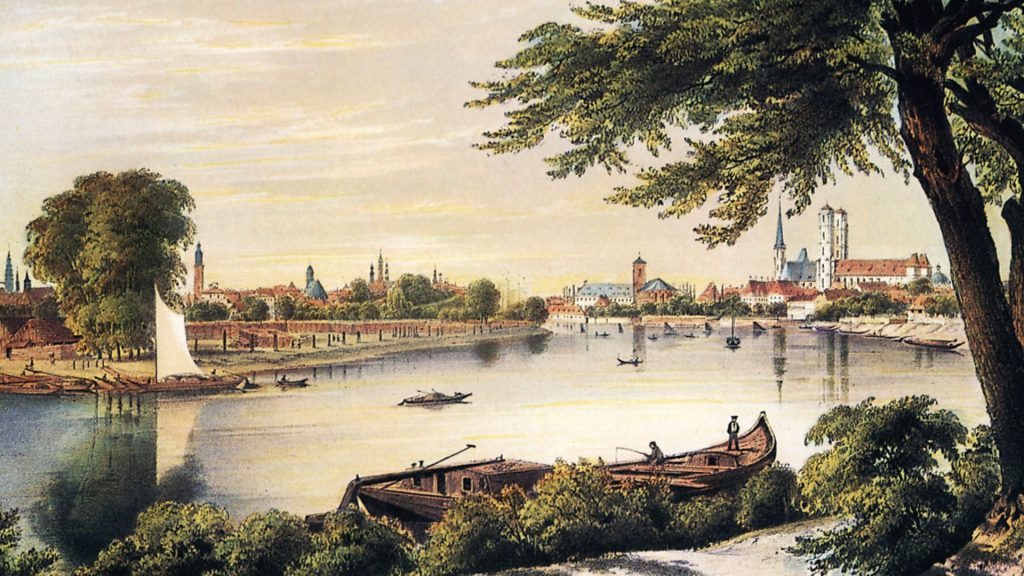

To understand its tangled history, you must start at Óstrow Tumski, Cathedral Island, a goal for pilgrims and tourists and a shrine for Polish nationalists.

The island may have been settled in the early eighth century by a mysterious tribe whose language may or may not have been something like Polish. At some later misty juncture it became, with all Silesia, a Bohemian (Czech) dukedom.

The earliest rulers of anywhere today recognisable as Poland were of the Piast ducal dynasty which emerged from Slavic tribes during the ninth century. In 990 Duke Mieszko proclaimed himself king, adopted Christianity and dutifully snatched Silesia from Bohemia. The booty included the island city in the Oder, called Vratislava after its evicted namesake ducal owner. His successor, King Boleus, built its first cathedral in 1163. After a century’s oscillation between Bohemia and Poland, Silesia’s island capital flourished again as an independent duchy. Sacked by Mongols in 1241, it was reconstructed Mongol-proof opposite the island on the Oder’s southern bank. Embraced by two wide moats and fortified walls, it would remain unconquered for 700 years.

At the junction of the Amber Road between the Baltic and Italy and the Via Regia linking North Sea Hanseatic states with Russia and beyond, the city’s good times rolled. Immigrants flooded from every direction. German merchants predominant, its language was German. Breslau’s golden age would last until the Second World War – though in various incarnations.

In 1355 it was reabsorbed (again) into the Kingdom of Bohemia which, 200 years later, was inherited by the Holy Roman Empire of the Austrian Habsburgs. In 1741, Frederik the Great nicked Silesia from Austria and Breslau became Prussian, becoming Germany’s third city when the German state was born 1871. Throughout its fluctuating sovereignties, Breslau had pragmatically got on with being itself. Then in 1945, almost overnight, every German was gone.

Today, Polish Wroclaw resembles one of those German picture book cities that have organically blossomed from medieval roots and later liberally adorned themselves with the 19th century keystones of Prussian cultural life.

Two structures are deemed emblematic: one supremely Polish, the other as German as German can get. The Raclawice Panorama, a circular canvas as long as two football pitches and high as two houses, is a paean to Polish national aspirations depicting a victorious 1794 anti-Russian uprising. Painted 1894 in Ukraine, it survived two world wars before Wroclaw created the picture’s big top-sized rotunda in 1985. The patriotic Polish Mecca has attracted to date ten million paying devotees.

The Centennial Hall is a worthy UNESCO World Heritage site. Imaginative and bold, awesomely gargantuan, it could only be Prussian. Designed by Max Berg, Breslau’s city architect, his 1913 Pantheon-like masterpiece marked the hundredth anniversary of Prussia drubbing Bonaparte. Beneath its luminous dome, Hitler ranted in the 1930s; here, in 1997, Pope John Paul II kindled wild dreams in his compatriot flock.

Until 1945 it was called the Jahrhunderts Halle (Centennial Hall). The communists renamed it Hala Ludwa (The People’s Hall) but Wroclaw’s post-communist council restored bravely in Polish its original German name: Hala Stulecia = Jahrhunderts Halle = Centennial Hall.

Breslau’s structural legacies, reset in their era, now seem assimilated as Wroclaw’s only historical inheritance. Its botanical gardens, shady promenades along the riversides and moat, maintained like a homage, are treasured as Wroclaw’s own. The Polish population’s nostalgic pride in an illustrious past with which it has no common ancestry seems not so much a wonder as a European miracle.

Breslau had taken to the Nazis with exemplary fervour. The Red Baron’s birth town was Hitler’s pride and joy. Hosting giant book burnings, the country’s second biggest synagogue blazed on Kristallnacht. The city’s 30,000 Jews had Breslau roots eight centuries old. Most perished in the camps. When the German armies overran Poland, nowhere had cheered more.

For most of the war, Breslau led a charmed existence. Far to the east, its great industries booming, it enjoyed the envied soubriquet ‘Germany’s air raid shelter’. The population soared to more than one million.

By New Year’s Day 1945 Russian tanks were within earshot. When women and children were permitted to leave, many thousands embarked on what later was called the Breslau Mothers’ Death March, joining floods of displaced Germans, eventually numbering more than twelve million, trekking hopelessly west. Today barely remembered, it remains the world’s biggest refugee catastrophe. With little food or drink, stumbling through snow, strafed sometimes by planes, temperatures frequently minus 20C, perhaps two million people died. Heart-rending pictures show roads lined with frozen corpses of grandmothers, mothers, children and babies. The women who had stayed considered themselves wise but within a few months their own fate was apparent.

By Valentine’s Day, the Red Army encircled Hitler’s Fortress Breslau. Goebbels billed the city an impregnable bastion that would never submit. For once he was almost right. Breslau resisted until four days before Germany capitulated.

Bombardments, air raids and house-to-house fighting rarely paused for three months. People secretly prayed for the Russians to come and end the daily nightmare. Few foresaw the greater nightmares the longed-for peace would bring.

On 30 April, Hitler killed himself. Breslau’s Nazi governor, Gauleiter Hanke, commanded young and old to stand and die for the fatherland and avenge the Führer’s martyrdom which Breslau, undefeated, never would betray. Two terrible days later, Hanke fled in a small plane and was never seen again. The city surrendered without another shot.

Breslau’s three month siege has been described as heroic and also as insane, but always as futile. Untold thousands had died but now came the bill. German Silesia had ceased to exist. Breslau was Wroclaw. All surviving Germans, permitted a maximum of 20 kilos possessions, were forced into columns to struggle on foot towards the bombed-out cities of their new home.

Churchill, they say, was horrified. The Yalta Conference carve-up of Europe had never envisaged millions of Germans pitched out of their homeland. It’s said he tried to intervene but Stalin was too strong, Roosevelt too weak. Some said – some still do – sow the wind, reap the whirlwind: they got what they deserved.

After the expulsion, so great was hatred for Germany that everything not easily Polish naturalised was systematically obliterated. The Russian proxy rearguard of resettled Poles repaid in hot blood the greater atrocities wreaked by Nazi armies on their ‘subhuman’ kin. Every German cemetery, seven centuries’ worth of headstones and bones, was expunged with picks and shovels from Wroclaw’s new red future, as if along with living Germans they must also expel their forefathers’ ghosts.

Wroclaw’s people today are more empathetic. The Poles and Ukrainians freighted to Breslau to repopulate the ruins were themselves refugees, evicted by Russia from annexed Eastern Poland. As thousands climbed from cattle trucks few knew where they were. Poland’s communist puppet regime dubbed Silesia initially ‘Poland’s New Territories’ but later opted euphemistically for ‘Poland’s Regained Territories’, confecting quasi-hoary annals from the spurious scholarship of nationalist historians.

In 2018, post-communist Wroclaw dusts its skeletons unflinchingly. Two world-class museums tell all there is to know. In the old royal Prussian palace, the Thousand Years of Wroclaw permanent exhibition tell Breslau’s history until its final day. The graphic portrayal of the Fortress Breslau months evinces no triumphalism, only compassion for other victims of the war. The vast History Centre picks up Wroclaw’s story from the German expulsion and the city’s resettlement through to Solidarity and communism’s fall. Instead of ‘new’ or ‘regained’ territories both museums employ the spade’s-a-spade term ‘annexed’. A young curator says, ‘Polish or German, it’s part of our history. Our little warning to the world’.

Polish children learn what their great grandads did to the Germans just as their counterparts in Germany learn what their great granddads did to the Jews and Poles. Most of them, it’s true, appear more interested in selfies. It was, after all, a long time ago. Yet in Breslau/Wroclaw it still seems extraordinary that no one (or not many, yet) on either side of the invisible border wants the price of common enmity to fade into oblivion.

Sealing their terrible shared past securely in museums seems also like an act of faith (if not a guarantee) that it will one day be for everyone reduced to ancient history.

The museums also show how Wroclaw grew from the rubble like a facsimile of its pre-war-Breslau self. Once saying ‘Breslau’ would have provoked at least a scowl. Now it passes unnoticed, often figuring in menus on as-Mutter-used-to-make-them regional dishes. In Breslau/Wroclaw’s seven century old Ratskeller – claimed as Europe’s oldest restaurant – with beer flowing freely, Poles and Germans chattering cheerfully around you, you might feel hard put to know where in Germany you were.

Today many Germans visit but only the oldest can remember Breslau life. Others wander the streets of their grandparents’ youth. They observe without rancour, regret or reproof, but with an atavistic pride in the captivating city their Breslau ancestors created.

Their university, among Germany’s best since 1670, figures today as one of Poland’s finest. Its nine Nobel Prize winners include Bunsen of the burner fame. From its famous rooftop viewpoint, medieval-Breslau time travellers would recognise immediately their old water hemmed city. The buildings around it would make their eyes pop, as do the eyes of Wroclaw emigrants, who left before its new EU golden age began.

The gleaming 2012 Sky Tower – at 212 metres, Poland’s highest building – soars above cranes erecting headquarters for companies like Apple, Amazon and Google as Wroclaw becomes a European high tech capital.

Major-chain hotels sprout around the inner ring road vying for prestigious city-centre footprints. Mammoth shopping malls, paint scarcely dry, are studded with names such as Dior, Gucci, Armani and Boss. Wroclaw is booming for similar reasons to Breslau in the Middle Ages. Germany west, Russia east, Scandinavia north, Italy and Austria south, you can almost hear the economy’s whizz. No wonder émigré citizens are hot-footing it home.

Cathedral Island’s antique lanterns were replaced by modern gas lamps in 1846. Among the pools of light and shadow, bells deepening the dusk, you need no guide book to convince you that for several different peoples this is hallowed ground. Its intact sense of separateness, still as set apart as when settlers first came, seems like an assurance that whatever else changes – names or tongues or sovereignties – some things always stay the same.

Polish, Czech and German pensioners, as nationally well-shuffled as a Brussels cocktail party, are amicably queuing for Wroclaw ice creams on the earth their forebears contested for centuries, tri-lingual conversations conducted mostly in smiles.

Vratislava/Breslau/Wroclaw’s so often reused bullet scarred bricks seem here enduring evidence that despite – or because of – Europe’s violent past and infinite diversity, still more unites it than divides.

This may not be the ethos of Poland’s current right-wing government but you can’t help thinking that the city on the Oder, cosmopolitan and confident and which has been around a bit, is revamping a worn adage into a motto for its next millennium: two wrongs – and often more – can sometimes make a right.