In the great Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges – whose master work is that literary revolution, The Garden of Forking Paths – we can see the value of weariness, exhaustion and the path/worlds they reveal.

This short story, on the surface, is about a Chinese spy. But in his attempt to show his German masters that a non-white man can give them something they want, Borges shows us the value of weariness and how weariness is created and used by others to create the world that they want. And how weariness, too, can be liberation.

I am reminded of a small moment on television recently. A little Guatemalan boy is sitting alone on an airport bench. A woman comes up to him, and the reporter who is filming the moment whispers to us, the viewers, that the woman is the child’s mother. She had been seeking asylum in the US, the reporter explains to us, and her son had been taken from her. She then went to court to sue for his return and she won.

The little boy sits quietly. He is weary. She walks up to him, her back to the camera. She kneels before him and hugs him. He is a rigid for a few seconds. She whispers in his ear and then he slowly rests his head on her shoulder. Gradually his little body begins to relax as he allows his mother to slowly rock him, talking in his ear all of the while.

The camera moves away, leaving mother and son to themselves.

It was easy to think of the weariness of that child, weariness from fear and anxiety and worry and of having to conform to the wishes of powerful strangers. Of having to make their world his world.

Which we all must do from time to time, even as adults. Freud calls that ‘civilisation’. And the weariness from that effort to be civilised, to form the rational out of the irrational, makes us weary. And leaves us open to manipulation and exploitation, too. To creating myth and then living and dying by it. Sometimes to our own detriment.

Recently, in the midst of making a documentary about great opera singers, I listened again to Pavarotti sing Nessun Dorma. Now there is something corny about doing that. Something even crass about listening to him sing that in his declining years, the crowds demanding those high Cs and not hearing what he does with bel canto. Or how he can make that voice do things that such a big, tall body should not be able to make happen. You can hear the weariness.

He had all of it: a meticulously-built career; travel back and forth to all of the great opera houses of the world – freedom of movement writ glorious and large. In the 1980s the only two recording artists bigger than he was were Elton John and Madonna. He was bigger than Michael Jackson and Prince.

He took to flaunting a white handkerchief to wipe his brow, much like James Brown, who was nicknamed ‘the hardest working man in showbusiness’. Pavarotti died at what would now be considered not old at all, perhaps worn out by the world created not only by him but for him and through him.

In Borges’ short story, the protagonist sees another world, many other worlds; The Garden of Forking Paths, visible though his weariness.

He can see how this very weariness, if he is aware of it, can create choice for him, a way to literally exist in the world that he chooses. Quantum physics tells us that this is possible, but who can take advantage of it?

The little boy at the airport, reunited with his mother, may take a long time to understand that the shock he endured at his separation, his retreat into the weariness evident on his face, create the reunion with his mother.

Or he could see the airport as a dream, as something he cannot believe. Or see his mother as his enemy, the life-force who left him behind and slowly, somewhere in himself, plot his revenge against her; or he could go to the place that he went to where he could comfort himself.

Borges’ short story tells us that all of those ‘forking paths’ and more are available. Most of us just don’t pay attention. But what happens when those who know the ‘forking path’, even unconsciously or sub-rationally, use it for their own purposes?

Donald Trump has quite simply exhausted much of the world with his unhinged tantrums and rants. All of this is housed in the ageing, comb-over head of an ageing plutocrat, from Queens, New York. He is the very epitome of the bad side of the ‘Bridge And Tunnel people’ – those from the outer boroughs of New York City who yearn to live and be on Manhattan Island but for one reason or another cannot make that happen.

Trump knows that this yearning for respect from the Elites is really the deep dream of what’s known as ‘Flyover America’ – the Midwest and the South, the regions of the nation that Elites jet across on their way from coast to coast.

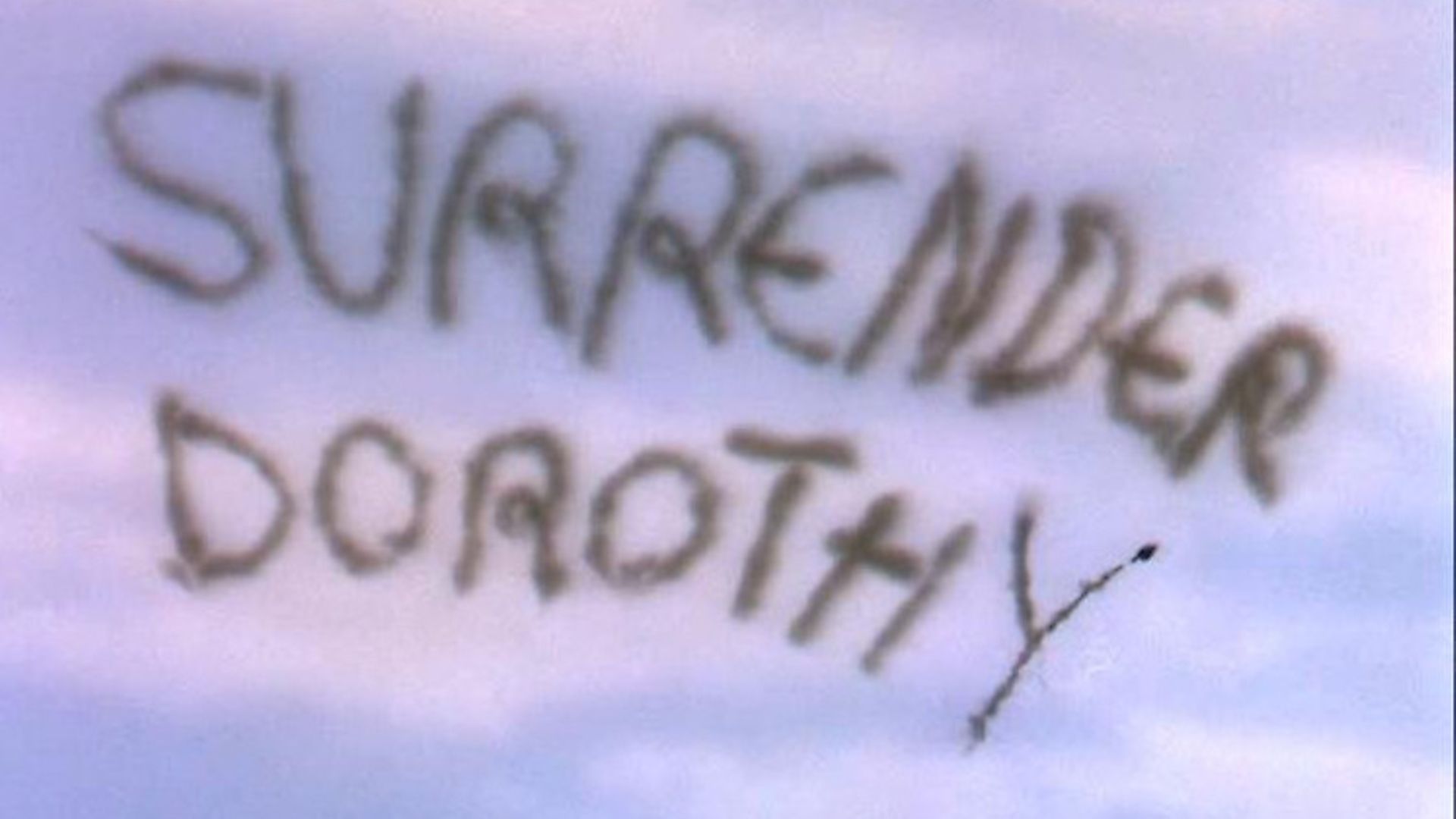

Trump hammers and bludgeons, lies and bullies, fashioning his world through the weariness of us condemned to listen. It’s the Wicked Witch’s ‘Surrender Dorothy’ writ large in our consciousness, and many do. Maybe most. From the weariness, the exhaustion. Summoning up, as a result: his world. His vision. Because it is there, available, real. As Borges points out. As a quantum physicist points put.

An MP stumbles out of the House Of Commons chamber after the ‘Meaningful Vote’ debate mumbling to a reporter that she/he (the name was not given) had no idea what just happened, in there. But the exhaustion of Brexit, the never-ending sheer absurdity of it had exhausted this parliamentarian, rendered numb and silent someone who should be shouting. But the Brexit reality was descending, even against all sense.

I tried, the other day, to pitch a television programme about Remain based on my hashtag #OrdinaryPeopleRemain, which allows ‘People’, not ‘the Elite’ to tell their stories.

There are stories there of being the children of dads who stood alongside the road every morning looking for work; of mothers who were dinner ladies; of 86-year-old grandfathers who voted Remain; of Northerners bucking against the myth that it was the North that drove Leave.

I told the producer all of this, and while she admitted that the majority of her colleagues were Remain and desperate to make a programme about it, it was the belief by Higher-Ups that Remain was too London-centric; metropolitan. That when the journalists travelled ‘outside’ there was a different story.

When Brexit was mentioned, the audience faded, many saying that they were weary of it, they could not understand what was going on. They just wanted everyone to ‘get on with it’, not sure what it actually was. But their exhaustion had created another world in which, somehow everything was going to be fine. Somehow. Even when Nigel Farage admits that he never promised that Brexit would be a success. But this alternative world, born out of weariness, still exists for many who choose Leave.

Donald Trump and a host of strong men all over the world are taking advantage of our literal and existential weariness. They are creating this garden of forking paths. They are making the realities that they want belong to us. And their credo of ‘we the people’ is what Borges writes at the beginning: ‘En la tierra y el mar, y todo lo que realmente pasa me pasa a mí.’

‘On land and sea, everything that really happens happens to me.’