Distracted by grief and anger following his brother’s terrible accident, Bottechhia overcame more struggles than war to become a cycling legend. CHARLIE CONNELLY reports.

Ottavio Bottecchia was up early on June 15, 1927. There were pinkish ribs of pre-dawn light on the horizon over the Veneto landscape as he swung his leg over the bike. It promised to be a hot one, a good day for a long, hard training ride.

At 33 it felt as if the hills were getting steeper and the sprints more gruelling. The Tour de France was challenging enough for a much younger man and, as he’d learned to his cost the previous year, there was nowhere to hide in the world’s toughest race. He needed to be at his peak physically and mentally if he was to reclaim the title he’d won in 1924 and 1925 but relinquished the previous summer.

He felt the cool morning air on his skin as he picked up pace, settled into his rhythm and went over the previous year’s Tour again. Had he become complacent? He didn’t think so: he’d prepared as meticulously as ever and was in peak condition.

Yet something went badly wrong. In the first nine stages he placed in the top 10 only three times. The tenth stage, Bayonne to Luchon, was the one he’d dominated most during his back-to-back wins, surely he would recover his race there and challenge again. As torrential rain reduced road surfaces to muddy torrents and the temperature plummeted to near freezing, Bottecchia had been horrified to find he had nothing left. His legs were heavy, his breathing raspy and laboured. Close to the summit of the climb he had stopped, dismounted from his bike, leaned it against a wall and sank to the ground in tears. He had been one of more than 20 riders to end their tour prematurely that day, but none hurt as much as the man who’d seen his dream of a third successive title vanish in the icy rain.

He was finding the 1927 season hard too, not just in terms of cycling. A crash at the Milan-San Remo race set his plans back and partly explained why he’d been unable to finish the 600km Bordeaux-Paris race the previous month.

Then there was Giovanni, the reason why he was back in Italy rather than at his French base in Clermont-Ferrand. It was still impossible to believe his brother was gone, killed by a car on a training ride. The driver was a wealthy industrialist and local government official, a fascist and a friend of Mussolini, who thought he could make the problem go away with 100,000 lire. Bottechhia pedalled harder as he felt the anger rise again in his chest. Fascists were abhorrent enough, without this.

What he needed that morning, he thought, was some company on the road, someone to distract his grief and anger. He called on a local rider, Riccardo Zille, but he was busy with admin for his business and when he arrived at the house of another friend, Luigi Maniago, he was up a ladder with a pot of paint, whitewashing the brickwork.

Still, being alone wasn’t such a bad thing. He could find his own pace and rhythm, set his own targets. It did leave him with just his thoughts for company though, and when he wasn’t thinking about Giovanni those inexplicable dips in form nagged at him.

He was conscious that, having come to cycling late, his career would be shorter than most. His opportunity to secure a financial future would last only as long as his legs kept pumping. And what about his lungs? He didn’t think he’d suffered any long-term effects from his wartime gassing, but who could be sure? He listened to his breathing for a while and pedalled on.

If it hadn’t been for the war he might never have taken up cycling in the first place. Bottecchia was 20 when he and Giovanni volunteered in the spring of 1915 and if anything it was a relief from the unbridled poverty defining their lives. His first name came from his position as the eighth child of a poor family, born in a tiny hamlet 50 miles north of Venice. His schooling lasted just two winters before he was sent out to earn a living. At 12 he was apprenticed to a shoemaker, then he became a builder’s labourer, hauling huge lumps of stone around in the heat and dust of high summer.

In the army he and Giovanni were assigned to the Bersaglieri, a unit of sharpshooters who carried a foldable bicycle with their backpacks to reach vantage points more quickly. Bottecchia proved so adept at fast hill climbs he was selected for dangerous missions delivering messages, often behind enemy lines, and he narrowly avoided capture several times through his nimbleness on two wheels. After the Battle of Caporetto in November 1917 he was caught up in a gas attack while providing covering fire for retreating troops. Incapacitated, he was captured but managed to escape from a march to a prison camp and return to his unit.

Demobbed at 24 he returned home and commenced work repairing and rebuilding a nation devastated by the war. He joined a cycling club and took up racing at weekends on an old bicycle. He was immediately successful in local races and by 1921 had created enough of a stir in the saddle to be offered a professional contract. Twenty seven was a little old to be a prodigy, but he became such an exciting prospect in a nation desperate for heroes that in 1922 La Gazzetta dello Sport set up a fund in his name, asking readers to contribute one lira each. Some 60,000 people did, including Mussolini. The fund combined with his race winnings to give Bottecchia a life of which he could barely have dreamed. He bought the substantial house close to his home village that he’d left that morning, telling his wife to draw him a bath ready for his return around three that afternoon, and became only the second person in the district to own a car.

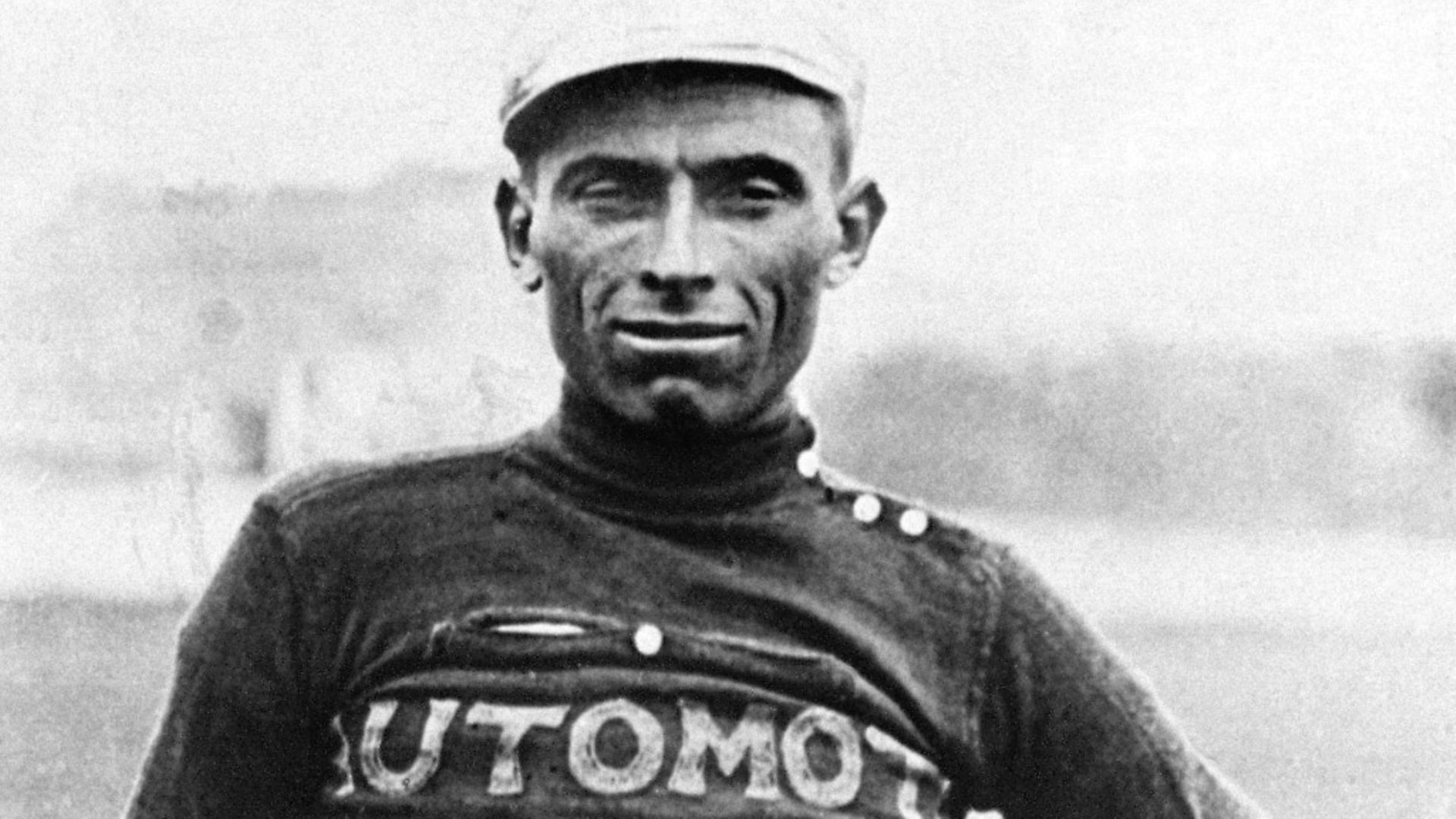

He was also able to establish his training base among the hill climbs of France, where he arrived with just enough French to say, ‘No bananas, much coffee, thank you’. A French cycling journalist described his arrival, ‘skin tanned like an old leather saddle and lines in his face deep enough to be scars. His clothes were ragged and his shoes so old they had lost their shape’.

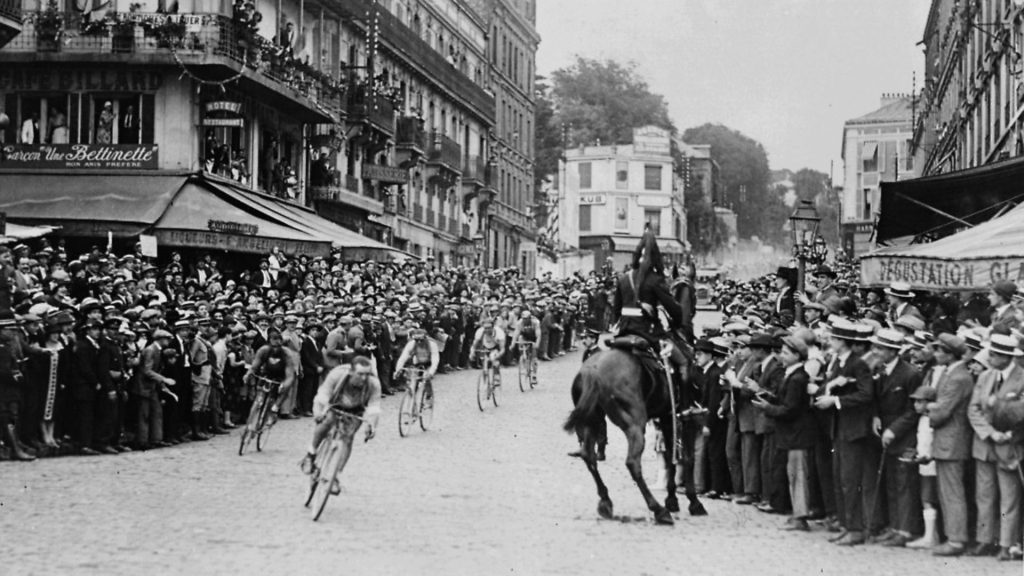

He finished second at his first Tour de France in 1923, and the following year he was supposed to be a support rider for the defending champion and Automoto teammate Henri Pélissier. With the champion slow to find his rhythm Bottecchia scorched ahead, winning stage after stage and breaking records for hill climbs. When he crossed the finish line in Paris to become the Tour’s first Italian winner he was 35 minutes ahead of his nearest challenger. The following year he increased his margin of victory to just shy of an hour.

It was midday now, the hottest part of the day. It had been a good ride so he stopped for a cold beer at the village of Cornino before pressing on north. He enjoyed the cooler air riding alongside the wide, stately Tagliamento river then picked up speed and made for the village of Peonis, feeling good, feeling fresh, noting the vines of young grapes stretching away from the road and wondering if they might become wine with which he would toast another Tour victory. The thought invigorated him and he hunkered down further over the handlebars, the wind roaring in his ears, his mind filled with the face of his late brother smiling his approval.

A farmer found him first, then other locals gathered. He lay motionless in the road, his bicycle nearby. Dark blood seeped from his nose and ears: he was alive, but only just. They carried him to an inn, laid him on a table and gave him the last rites. He was transferred to hospital where he died 12 days later having barely regained consciousness.

The cause of his death was never established. One theory was that he was ambushed by fascist thugs. He had always been open about his socialism and anti-fascism and with the connection of a leading fascist to his brother’s death less than a fortnight earlier he might have been silenced. Many years later a Sardinian docker dying of stab wounds on a New York quayside reportedly confessed to killing Bottecchia as a hit man for a betting syndicate. Another rumour had the farmer making a deathbed confession of catching Bottecchia stealing fruit from his trees and throwing a rock at him.

Whether foul play was involved or the heat and the beer and the advancing years had combined to make him fall and hit his head, the short, improbable and glorious career of Ottavio Bottecchia created one of cycling’s greatest legends, his death one of sport’s great unsolved mysteries.