In the bicentenary of Frederick Douglass’ birth, the city of Newcastle is remembering the pivotal, if little-known, role it played in the life of one of America’s greatest sons.

When President Donald Trump spoke at a breakfast to launch black history month last year, he gave the impression that he thought Frederick Douglass – the most eminent African American leader of the mid-19th century – was still alive. Douglass, Trump explained, ‘has done an amazing job’.

The Frederick Douglass Foundation gently mocked the president’s gaffe, explaining how Douglass’s contemporary legacy was so immense that it was perfectly legitimate to talk about him in the present tense. The foundation had a point. Douglass’s accomplishments are legion. But the story of how his travels to northeast England led to his ultimate emancipation is less well known.

Born in Cordova, Maryland, 200 years ago, Douglass escaped slavery in 1838 and became a tireless campaigner for black emancipation and racial justice, as well as advocating equal rights for women, Native Americans and immigrants.

He was a passionate supporter of the Temperance movement, set up a crusading newspaper, The North Star, and battled to end segregation in public schooling.

After the Civil War, Douglass continued his efforts to secure equality of opportunity and constitutional protections for newly freed African Americans and even served as minister to Haiti under president Benjamin Harrison.

In 1872, without his consent, Douglass became the first African American nominated for US vice president as the running mate to Victoria Woodhull of the Equal Rights Party. He even received one vote at the Republican National Convention for the office of president in 1888.

Douglass was an inspirational orator, an elegant writer and a sophisticated, progressive social thinker. He also had a remarkable capacity for self-promotion.

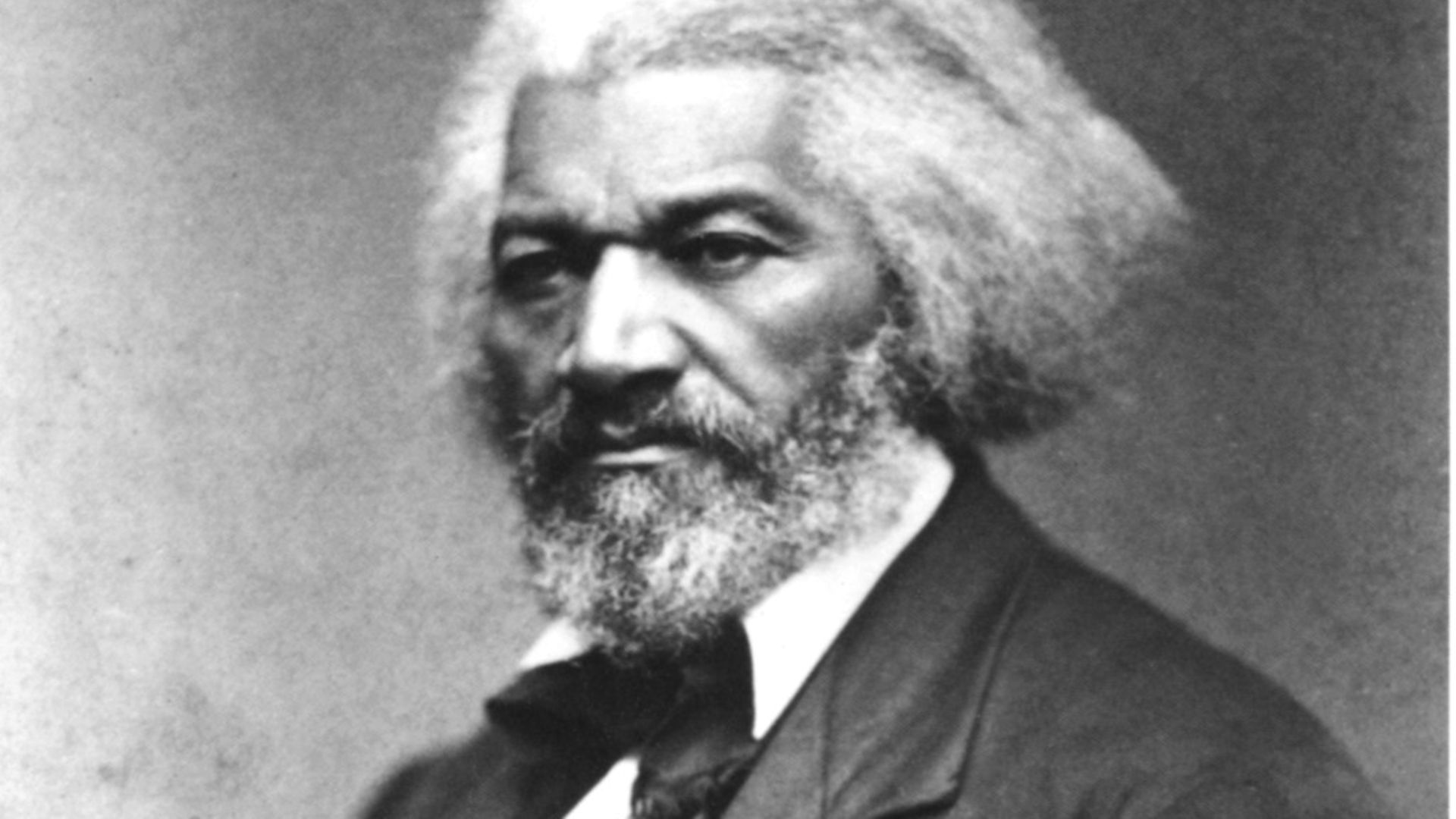

In 1841, he sat for his first photographic portrait and went on to become the most photographed American of the 19th century.

He appreciated how this new and rapidly evolving medium would allow him to create his own dignified public image and challenge crude racist stereotypes of African Americans.

The 160 images made of Douglass during his lifetime, together with a number of oil paintings, his speaking tours and the publication of several versions of his life story, kept him in the public eye. Since his death in 1895, Douglass has appeared on US postage stamps and coins. He has been portrayed – with varying degrees of fidelity to the facts of his life – in a host of novels, poems, songs, films, television series and documentaries. He features on at least 110 murals and numerous other public monuments.

Douglass’s celebrity was truly international. He visited Britain and Ireland on three separate occasions. Everywhere he went, he made an impact. In Ireland, Douglass’s commitment to Irish Home Rule is commemorated in the Solidarity Wall mural on Belfast’s Falls Road. His time in Ireland is also the inspiration for Colum McCann’s 2013 novel TransAtlantic.

Earlier this week, a plaque was unveiled in Newcastle upon Tyne, marking perhaps the most significant of all Douglass’s transatlantic connections. It celebrates a relationship that literally changed Douglass’s life.

Douglass first came to Tyneside in 1846 and, over the course of several visits, spoke in the region on at least 16 separate occasions. In Newcastle, the charismatic ex-slave met and formed a close bond with the Richardson family: Henry, his wife Anna and sister Ellen. The Richardsons were Quakers, abolitionists, and involved in peace activism and campaigns to expand the suffrage, including votes and other rights for women.

Douglass was struck by the peculiar intensity of Tyneside’s anti-slavery passions. In late December 1846, he told a cheering crowd of his pleasure at seeing ‘so large an audience assembled for so noble a cause’ and of his joy ‘that Newcastle had a heart that could feel for three millions of oppressed slaves in the United States’.

Douglass had good reason to appreciate this local support. Over the previous few months, the Richardsons had been raising money to formally purchase Douglass’s freedom. On December 12, 1846, Hugh Auld, brother of Thomas Auld, who was Douglass’s nominal US master, registered the bill of manumission that officially made Douglass a free man.

The decision to buy Douglass’s freedom was not without its critics. Some felt that the purchase legitimised the idea that any human being could ever be owned by another human being, to be bought and sold like any other item of property. Douglass himself was more pragmatic. When he visited the region for the final time in 1886, he announced that he did so primarily to meet again the ‘two ladies who were mainly instrumental in giving me the chance of devoting my life to the cause of freedom’.

He added: ‘These were Ellen and Anna Richardson, of Newcastle upon Tyne… without any suggestion from me they… bought me out of slavery, secured a bill of sale of my body, made a present of myself to myself and thus enabled me to return to the United States and resume my work for the emancipation of the slaves.’

The plaque to Douglass and the Richardsons opens up a rich, largely hidden, history of racial diversity in a place traditionally thought of as one of the whitest sections of the United Kingdom.

Douglass, like Olaudah Equiano before him and Martin Luther King and Muhammad Ali a century later, came to Tyneside and found there a remarkably warm welcome.

Of course, ugly, sometimes violent expressions of racial, ethnic and religious intolerance have occasionally punctuated the region’s history. Nevertheless, Douglass’s story and the ties he forged with the Richardsons and other local ‘people of goodwill’ reflect the region’s progressive political traditions. As Douglass put it, in a quote that adorns the Newcastle plaque:

I will unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.

Brian Ward is professor in American Studies at Northumbria University, Newcastle; this article also appears at www.theconversation.com