Bayern Munich now seem all-conquering. But for much of the bavarian giant’s history – particularly under the Nazis – it was a very different story. NEIL FREDRIK JENSEN reports

If ever a club should be labelled as part of the football establishment then Bayern Munich would certainly fit the bill. FC Bayern, as they are known, not only represent a prosperous and stylish city, they also carry the flag for Bavaria and the German nation.

The club has an assured – some say arrogant – swagger about it, and a record that explains why. The team has won the last seven Bundesliga titles (29 in total) and until the coronavirus intervened, looked poised to add to that tally. They have also lifted the European Cup or Champions League five times, equal to Barcelona and behind only Liverpool, AC Milan and Real Madrid in terms of total triumphs.

Behind the scenes, they are the epitome of modern European corporate football, their revenue streams and wage bill dwarfing most other clubs. They also have some of the biggest names in German industry among their shareholders, Adidas, Allianz and Audi, to name just a few.

Bayern, then, represent the very embodiment of German dominance and might. But this was not always the case. Indeed, while they might now be the biggest club in the country, for much of their history they were not even the biggest club in their own city. Bayern’s ascent to its current, dominant position has meant navigating the dark and complex history of Germany’s 20th century. Their route to establishment pre-eminence has been far from straightforward.

The club was founded in the then decidedly bohemian Munich suburb of Schwabing after a meeting in a restaurant in February 1900, hosted by a Berlin photographer called Franz John. He had successfully recruited a group of men from another local sports club, Münchner TurnVerein 1879 (MTV) – including, incidentally, the German-born British sculptor Benno Elkan, who designed the Tottenham cockerel that stood atop the old White Hart Lane ground – who were disillusioned with that organisation’s lack of enthusiasm for the relatively new sport of football.

The early years were precarious. To solve financial problems and find a secure venue, Bayern joined with the Münchner Sport-Club in 1906. They retained their independence, but as a concession ditched their black colours in favour of MSC’s red and white – which are still the colours worn today.

The following year, Bayern moved to a new ground on Leopoldstraße. The first game saw them thrash local rivals FC Wacker 8-1. It was a small step towards local dominance, but many more were to come. They first had to progress through the often confusing German football pyramid, slaloming their way through various Bavarian leagues.

In 1910, they became Eastern District champions (they held the title for the following year) and saw their first player capped for Germany, Max Gablonsky. Of greater significance, though, was the emergence, in this period of the man who would later be credited with laying the foundations for Bayern’s subsequent ascent.

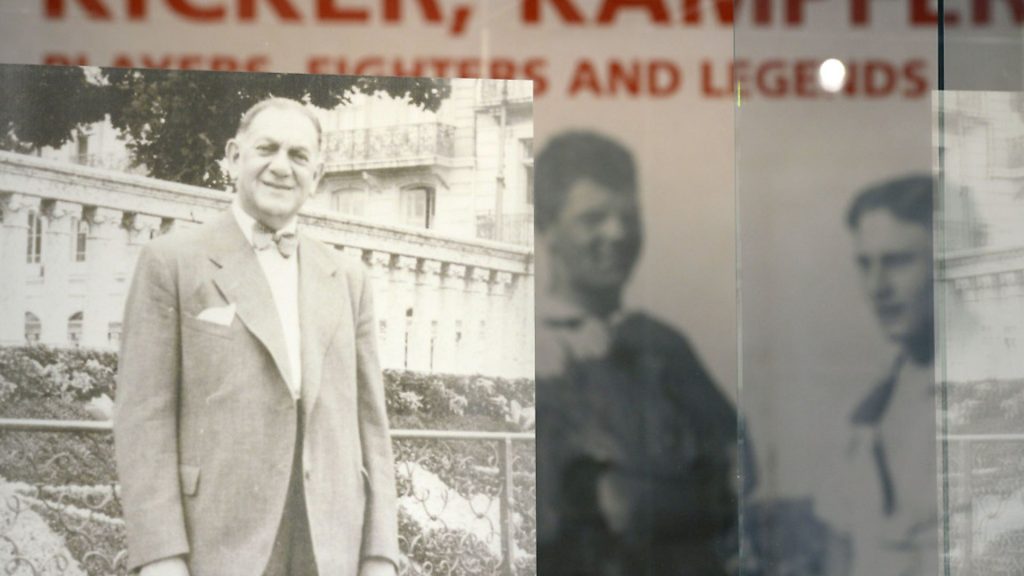

Kurt Landauer, a Jewish accountant with a background in advertising, had been a player for the club and saw an opportunity to build it up to challenge Bavaria’s biggest two sides, both from Franconia, in the north of the state, 1. FC Nürnberg and SpVgg Fürth. Landauer became Bayern president in 1913, after his popular predecessor Angelo Knorr was arrested for homosexuality. One of the new man’s first acts in charge was to poach English coach William Townley from SpVgg Fürth, which at the time had the most advanced facilities in Germany and was quickly becoming the country’s largest club.

Townley and Landauer did not have long to realise their vision for Bayern before their two countries were at war with one another. All football was suspended and two thirds of Bayern’s members and players joined the German military, with no fewer than 60 members losing their lives during the First World War. Landauer himself became a decorated officer and survived the conflict.

Bavaria at the end of the war was a spectacularly volatile place – until its bloody overthrow it was even the home of a short-lived Soviet Republic – but Bayern were soon back on their feet. Landauer returned, as did Townley, who coached there until 1921, helping the club earn local and regional titles.

Bayern’s progress continued through the 1920s and with crowds growing, this necessitated a move to share local rival’s TSV 1860’s Grünwalder Stadion, in 1926. The same year, Bayern won the southern German championship, but failed to shine in the national play-offs, by which Germany’s overall champion was decided.

Six years later, they finally won the national prize, beating an Eintracht Frankfurt team that had pipped them to the south German title. Some Bayern fans even cycled the 100 miles to Nuremberg to watch the final.

Bayern’s team that day included some illustrious names from the club’s history, including full-back and captain Conrad Heidkamp, centre half Ludwig Goldbrunner, Josef Bergmaier, Franz Krumm, and the much-travelled, and some said mercenary, centre forward Oskar Rohr, one of the first players to venture abroad. This was Germany’s last title before the Nazis came to power – having been incubated in Bayern’s own Bavarian backyard – and there is a certain irony that it was contested between two clubs both considered to be ‘Jewish sides’, Bayern due to the involvement of Landauer and manager Richard Kohn, and Eintracht, owing to the religion of their three main shareholders.

When the Nazis took over in 1933, Landauer and Kohn were forced to leave, along with Otto Beer, the youth coach, and others. Despite the purges, Bayern did not lose their reputation as a ‘Judenklub’ and were unfavoured by the new regime.

The Nazis simply didn’t trust Bayern as they had a habit of appointing presidents who rarely toed the party line. They had more affinity with cross-city rivals TSV 1860, which was more representative of Munich’s working class. Indeed, despite Munich’s position as an epicentre of the Nazi movement, the party never made much inroads into Bayern. The only Nazi to become president was Josef Sauter, and that was not until 1943.

The Nazi regime did its best to make life hard for Bayern and club membership and player availability all declined as a result. From the high point of their first title in 1932, Bayern stalled and they never competed for the highest honours under the Nazis.

This did not mean they did not have talented footballers. Goldbrunner was one of two Bayern players who represented Germany in the 1936 Olympics, along with an emerging forward named Wilhelm Simetsreiter, who scored three goals in the tournament and is said to have made it a point to have his picture taken with Jesse Owens, the African American athlete who exasperated the Nazis by winning four gold medals at the games. The host nation disappointed, however, going out to Norway 2-0 in the quarter-finals, in front of Goebbels, Göring, Hess and Hitler. The Führer, who had never seen a football match before, and had originally planned to watch the rowing, left early in a huff.

When the war came, it hit Bayern particularly badly. There was a theory the club had more members sent to the frontline than any of their rivals. Around 60 members fell on the battlefield and others went missing in action. Goldbrunner’s teammates from that 1932 final, close friends Josef Bergmaier and Franz Krumm – one of the scorers that day – both died within days of each other in March 1943, on the Eastern Front near to the Russian city of Oryol.

That same year, the club staged a small act of defiance against the Nazis, during a game against a Swiss Select XI in Zurich. In the crowd that day was Landauer, who had fled to Switzerland after a spell in Dachau concentration camp during the 1930s. The Bayern players spotted him in the stands and went to applaud him, much to the frustration of the accompanying Nazis.

Incidentally, the Bayern player who had the most eventful war was Oskar – Ossi – Rohr, who had scored the other goal in the 1932 final. His ambitions – much criticised in Germany at the time – had seen him move abroad in the 1930s to play in Switzerland and France, where he was living when the conflict broke out. He fled to the southern, unoccupied area of France and was declared persona non grata by the Nazis. Exactly what he got up to during this period is unconfirmed, although some reports describe him joining the French Foreign Legion. What is clear is that he was arrested in 1942 in Marseille and, after serving a sentence in Strasbourg Citadel, was handed over to German authorities. He was interned in a concentration camp at Karlsruhe-Kieslau before being sent to the Eastern Front, where he was permitted to join an army football team. Shortly before the end of the war, a German pilot recognised him from his footballing days and offered him a flight back to Germany, away from the advancing Russians.

Back in Munich, the main stand and terracing at the Grünwalder Stadion had been destroyed during the war and the pitch was covered in bomb craters. The club’s trophies, however, were safe, having been kept out of the hands of both the Nazis and the Allies. In 1940, the government had appealed for the donation of metals, to contribute to the war effort. While other teams had handed over their cups and medals in response, Bayern had held on to theirs. In 1942, with the city coming under heavy aerial bombardment, Conrad Heidkamp – another star of the 1932 triumph and later a wartime Bayern manager – and his wife crated up the silverware and drove it out to a farm outside Munich where she had stayed as a child, for safekeeping. As US forces advanced on Bavaria in 1945, the couple, fearing the items could be looted, returned to the farm to bury them.

Once peace finally arrived, football – as after the First World War – followed quickly in its wake. The Americans who took control of the region were reluctant to allow club activities and mass gatherings, but Bayern were playing again just six weeks after the surrender of Germany. In 1947 Landauer – many of whose relatives had been murdered in the Holocaust – returned from exile for his third stint as club president.

To recover from not only the war but the doldrums of the Nazi era was a significant challenge for Bayern, though, and progress was faltering. A total of 13 coaches were hired and fired between 1945 and 1963 and the club struggled on and off the pitch. They was relegated from the southern league in 1955 – before being promoted the following season – and were on the verge of bankruptcy towards the end of the decade.

Financial stability came with the election of local industrialist Roland Endler as president in 1958 – not the first or last time that the club had benefited from its close relationship to Munich’s powerful captains of industry. Stability on the pitch followed, with the club’s best years in the southern league coming under Endler’s stewardship. This meant that what was to follow was particularly controversial.

A new nationwide professional league was to be launched in 1963. The constitution of the Bundesliga, as it was called, was to be determined using a number of criteria, including form over the past decade, economic stability… and geography.

The authorities wanted only one club per city in their new league and, despite Bayern’s recent form, it was TSV 1860 who got the nod. Bayern considered the decision an outrageous injustice, but it may have proved to be a blessing in disguise. The club were still not ready to compete at the top, on a financial basis, and their promising young talent – among them, names such as Franz Beckenbauer, Sepp Maier and Gerd Müller – might not have been given the time and opportunity to flourish with such a rapid acceleration.

President Wilhelm Neudecker, an uncompromising building contractor, disgusted at the decision to exclude his club, instigated a period of restructuring and professionalisation that saw the team promoted to the Bundesliga two years later, alongside a team that would develop a strong rivalry with them in the 1970s, Borussia Mönchengladbach.

Neudecker, a larger-than-life character and a very successful businessman, had promised he would walk around Lake Tegernsee, in the Bavarian Alps, with 500 fans if Bayern won promotion. He very much enjoyed the 13-mile hike.

Progress was now rapid. Bayern soon made an impact in the Bundesliga, finishing third in their first campaign, two places below rivals and champions TSV 1860 who were going through a golden period of their own. Bayern also won the DFB Pokal – Germany’s main cup tournament – and, the following season, lifted their first European prize, the Cup Winners’ Cup, beating Glasgow Rangers 1-0 in, of all places, Nuremberg.

Bayern’s first Bundesliga title arrived in 1969, eight points separating them from second-placed Aachen. It was the moment they finally eclipsed cross-city rivals TSV 1860, who would be relegated the following year and go on to endure long spells out of the top flight, where they have never been serious challengers since.

The change of fortunes reflected broader social trends in Bavaria. The forces that had helped power 1860 – with its once mighty working class fanbase – declined, as the city’s manufacturing sector waned; while for Bayern – boosted by its long-established links to now-booming local corporations – greatness beckoned.

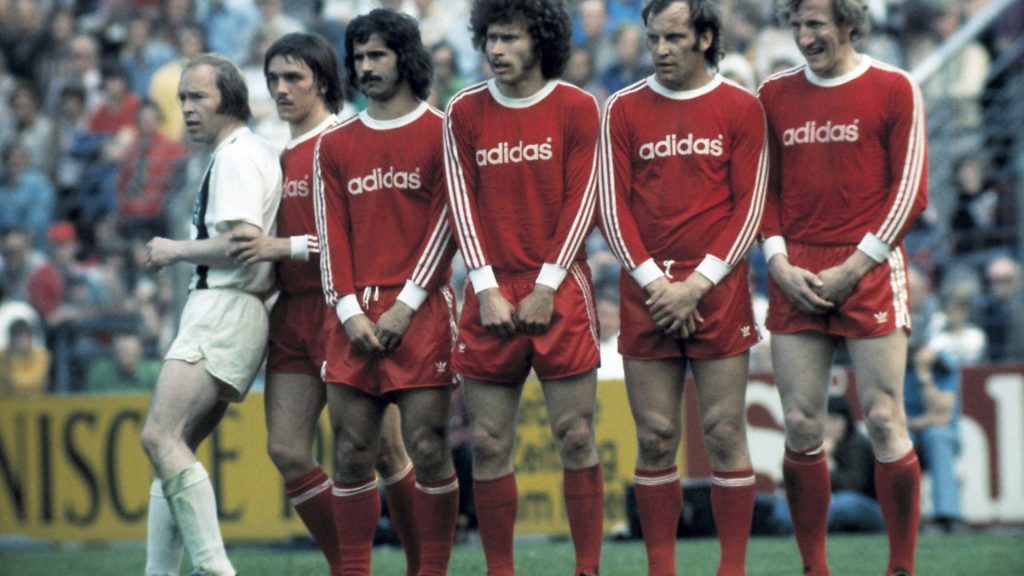

The club was now on the brink of becoming a major European power and added two more promising youngsters – Paul Breitner and Uli Hoeneß – to their outstanding home-grown players. Bayern’s success was based on an extremely high level of fitness as well as progressive techniques such as zonal marking and ‘pressing’, which has a far longer history than most people realise.

Bayern’s battle with Mönchengladbach defined German football in the 1970s, the former considered obsessively efficient and boring, the latter reputed to be bohemian and cavalier. The truth was far removed from the comparisons made by the media and supporters alike. There was no more bohemian character than Bayern’s Breitner, a wealthy Bavarian with an afro haircut who claimed to be a Maoist, and for every Günter Netzer, the long-haired, disco-owning playboy, Gladbach had a conservative stabiliser like Berti Vogts.

Bayern won three consecutive European Cups between 1974 and 1976, each time showing determination, patience and ruthlessness in wearing-down their opponents. Even today, the fans of Atlético Madrid, Leeds United and Saint-Etienne will claim they were denied glory by Bayern’s resolve and rapier-like finishing. The 1970s really did belong to Bayern and the city of Munich: the 1972 Olympics, the 1974 World Cup; and FC Bayern, the club of ‘Der Kaiser’ Franz Beckenbauer and Gerd ‘Der bomber’ Müller.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Bayern continued to attract star names, good and bad headlines and intense media attention. Their constant tabloid presence earned them the nickname ’FC Hollywood’, but it was not until 2001 that they won the Champions League again, beating Valencia in the final in Milan. They won it again in 2013, overcoming their newly-established Bundesliga rivals Borussia Dortmund at Wembley.

The current era has seen Bayern not only completely dominate German football, but also consolidate their position as one of the most financially powerful clubs in the world, playing at the wonderfully aesthetic Allianz Arena.

Since arriving in the Bundesliga in 1965, Bayern have never been relegated and only finished outside the top five on six occasions – and not once for 25 years.

Bayern are not only very astute commercially, they have also developed a strategy of buying players from chief rivals, using the club’s reputation and wealth to entice them away. This not only strengthens Bayern’s squad, it also weakens the opposition.

They have also hired some of the world’s most coveted coaches, including Pep Guardiola, Carlo Ancelotti and Louis van Gaal. Everyone has some form of success at the club, but sometimes, success is not enough. Even Guardiola came in for criticism during three trophy-laden years at Bayern, largely because he failed to win the Champions League. They want to win and win big and their legendary indomitable spirit continues to frustrate so many of the club’s opponents.

It took the club a long time to reach this commanding position. They don’t want to relinquish it any time soon.