Under Corbyn, the Labour movement is shattering, with many struggling to stay on board. NATHAN LLOYD explores the party’s history to find where its essence is really found.

Contrary to popular belief, it was the late Tony Benn – not Tony Blair – who was brave enough to identify that ‘the Labour Party has never been a socialist party’. While he was quick to emphasise that there had always been a minority of doctrinaire socialists amongst his progressive comrades, it was an honest observation about the basic truth of that coalition. The Labour Party has always been a social democratic party in practice and passionately socialistic in principle.

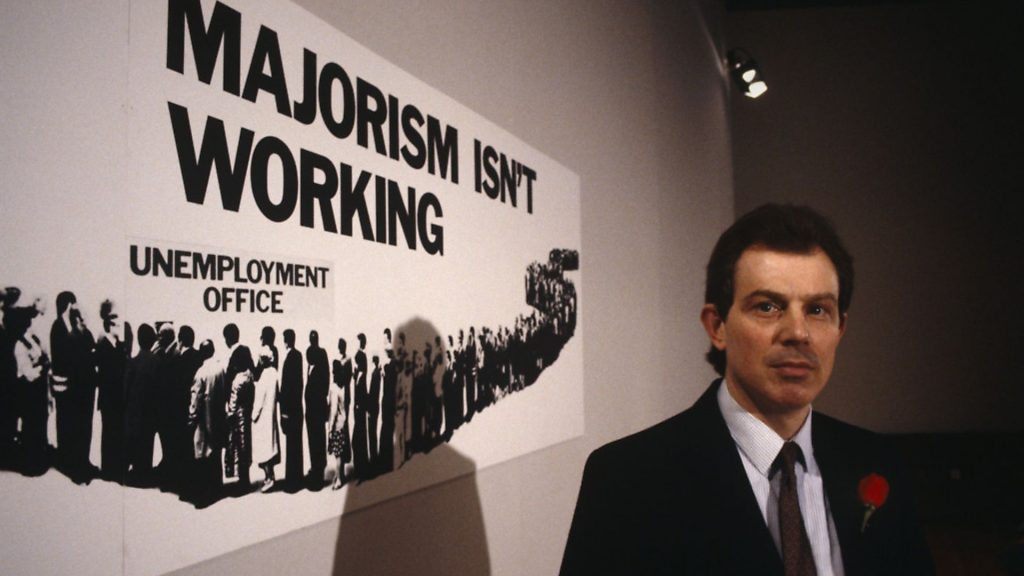

It’s a bizarre development, therefore, that moderate social democrats who best reflect Labour’s founding aims now feel alienated from the party’s brand. But perhaps the greatest irony of all is that a mythology in which Blairites are traitors and Attlee’s New Jerusalem is misrepresented as a Marxist construction has its roots in the spin which once proved to be so advantageous. In the end, it all comes down to the lie that New Labour wasn’t Old Labour.

When Jon Lansman, the founder of Momentum, makes the ridiculous claim that Tony Blair was never in the right party and that there will be no return to his politics in Labour, one wonders what his problem is with the ethical socialism of Clement Attlee.

It’s more worrying when former comrade Chuka Umunna irresponsibly suggests that Labour’s only period of successive victories may have been ‘exceptional’ or even an ‘aberration’ in the party’s history, that the last few years of chaos and misdirection represents the past reasserting itself after a decade of deviation.

That couldn’t be further from the truth. While it’s undeniable that thousands flocked to join the party because they recognised change in Jeremy Corbyn, his leadership has not only been a decisive break with that of Blair and Brown, but with every other leader who has ever taken Labour into government.

It’s understandable why, at first glance, many perceive Blair and not Corbyn to be the aberration. He was Labour’s first prime minister after a period in which the country had spent nearly two decades supporting a wholesale transformation of the economy.

It’s difficult to relay the necessity for centre-left parties to adapt to a changed political and economic context when the loudest – often most privileged – voices are usually more comfortable with being the principled opposition to a society with the wrong principles.

Blair accepted the fundamental reality, which Callaghan had understood decades before, that Keynesian orthodoxy as it once existed was dead. He regarded the trade union reforms, which Wilson had previously struggled in vain to implement, as being the sad necessity which Attlee had warned that they one day could be.

Ultimately, though, it is Blair’s removal of Clause IV which for many has been immortalised as the surest proof that he never belonged to a party which bore it on every membership card for a lifetime. But even when Clause IV committed the party to full public ownership, it was more of a contradiction than the defining feature it’s misremembered as.

Labour has, first and foremost, always been dedicated to parliamentary representation as a means to advance the labour movement (a movement, incidentally, which is distinct from socialism, even though the two are historically aligned).

It was Keir Hardie who was the first to see the inherent dangers in a constitution which placed dogma above the principal aim of governance. There were several unsuccessful attempts to whittle down Labour’s progressivism to a single objective, and on the fifth attempt – at the 1907 party conference – Hardie gave perhaps the most damning assessment of the role such a clause would have: ‘Suppose this amendment were carried. What followed would be that only men who were socialists could be members of the party in the House of Commons. Did the movers of the amendment want to bring about such a result?’

For Hardie – and the trade unions similarly opposed to the move – the party’s status as a broad church dedicated to winning power was a vital component to its success. It was the Lib-Lab pact and a parliamentary alliance with social liberals that was just as critical in those early decades as the relationship with the trade unions.

In that same year, Labour also made the decisive step of finally cutting ties with the party’s Marxist faction, which had always been an impediment to Hardie’s goal of a movement prioritising ethics over simple economics.

While Labour would eventually adopt Clause IV a few years after Hardie’s death, any strategy about how it would ever be implemented remained obscure.

Labour’s own concept of socialism – once described by Harold Wilson as owing more to Methodism than to Marx – developed from Christian values, a commitment to the empowerment of the vulnerable and the case against the only form of capitalism which then existed: no welfare state, minimal workers’ rights and ruthlessly laissez-faire.

While public ownership was then viewed as the most efficient means to bring about greater social justice, those goals never meaningfully translated to the overthrow of the capitalist system or the abolition of private property. It’s Labourism – not traditional socialism – which has always provided the pragmatic core of the party’s ideology and, while Clause IV may have provided spiritual sustenance for party members, it increasingly became an impediment to Labour’s long-term electoral prospects.

When Hugh Gaitskell attempted to remove Clause IV, in an earlier attempt at modernisation, he was typically characterised as a closet Tory. It was Attlee, who previously supported the party moving away from what he called ‘futile left-wingism’, who later came to his defence after that failed attempt to return Labour’s constitution to its original state.

Reflecting on the criticism of Gaitskell, he stated: ‘It was an error to regard him as in any way a right-wing reactionary. Nor was he a cold-blooded reactionary. In so much as these terms have any validity, I should regard him as left of centre.’ In Attlee’s experience, the centre-left was precisely where a successful party leader needed to be.

Attlee’s newfound status as a hero of the far-left is not only bizarre, but it’s entirely retrospective and certainly wasn’t shared in his own era. This was a man who believed in private education, took pride in his hereditary peerage and coined the phrase ‘the enemy within’ to describe ideologues using the trade unions to call wildcat strikes. While sharing the idealistic radicalism of every Labour leader before gaining power, he believed in precisely what he implemented – Beveridge and Keynes, rather than Marx and Engels.

He was instrumental in creating Nato, gave Britain its nuclear deterrent and was a world leader in the fight against communism, which he recognised as antithetical to freedom. Reading the far-left criticism in the decades before the urgent clamour to claim his legacy, it’s hard not to look at the accusations that Attlee was a ‘New Liberal’ in disguise or the condemnation of his ‘imperialist’ military interventions without seeing parallels with the wholly false caricature of Blair as a neo-liberal warmonger.

Meanwhile, the modern far-left’s celebration of Attlee’s nationalisation agenda is as divorced from context as its condemnation of Blair’s post-Thatcher policies. This was an era in which there was an appetite across the political spectrum for greater state control of industry and institutions. These weren’t mere ideological aspirations; they were fresh and largely untested economic alternatives in the centre ground of politics.

Future Tory prime minister, Harold Macmillan, was calling for a programme not all that dissimilar to Labour’s and Viscount Astor was insisting on nationalisation of the land. Nationalising a fifth of the economy – almost exclusively industries already failing in private hands – and decisively ending that programme to preserve a mixed economy, led to accusations that Attlee had betrayed socialism rather than having corrected many of the injustices which inspired Labour’s founders in the first place.

Subsequent manifestos in the 1950s made pledges to enterprise that wouldn’t be out of place in 1997. Emphasising the importance of a competitive private sector and introducing the concept of tenants buying their own council houses – which was later pinched and rebranded as a Tory innovation – were all commitments made at elections in what came to be known as the Golden Age of Capitalism.

None of that undermines the radical credentials of the Attlee government, but they are facts which are often buried when it comes to judging the extent of Labour’s supposed ideological evolution. The myth that the last Labour government was indistinguishable to Thatcherism or was neo-liberalism by stealth isn’t one that I recognised growing up on a council estate. From the vantage point of those of us who not only wanted but desperately needed Labour in power, it was still the same party.

And it was the most redistributive government since the 1960s. It tripled spending on the NHS, with more than 44,000 more doctors, free prescriptions for cancer patients and free eye tests for the over-60s marking the single biggest investment in the health service since its creation.

There was an increased state pension, while the Winter Fuel Allowance, Pension Credits, free television licences and bus passes for the elderly helped lift 900,000 pensioners out of poverty. The government doubled spending on education as well as the number of apprenticeships, introduced Sure Start centres, Tax Credits and paternity leave, increased child benefit, hired 42,000 extra teachers, brought in free entry to art galleries and museums as well as Education Maintenance Allowances for sixth formers and took 600,000 children out of poverty. That war on want extended globally too, with the overseas aid budget doubled and the world’s poorest countries having 100% of their national debt written off. That resulted in three million people being lifted out of poverty each year.

Tuition fees, while understandably controversial, ultimately had a progressive effect. I was a beneficiary. There were university places available for everyone in my comprehensive if they had the inclination to attend. Whereas before, university would have been almost unthinkable for someone like me, there were record numbers of working-class people in further education because the places were there. Even the much maligned PFI at least had egalitarian intentions.

There were schools and hospitals built rapidly after decades of neglect and an understandable reluctance to finance them through the old tax-and-spend mantra which would have undoubtedly cost an election. Food banks, which are now a weekly reality for my neighbours, were totally unknown to me as a concept despite recent Tory attempts to claim otherwise.

It wasn’t bland centrism preserving the status quo. It was the most radical government since the Attlee years. Not only in terms of the constitutional reforms, but in honouring age-old priorities. The national minimum wage and ridding the Lords of hereditary peers had been goals of the original Fabians, which had gone unfulfilled by successive Labour prime ministers.

Homelessness decreased, violent crime was down and Britain was leading the fight against climate change. The Climate Change Act made us a global leader in cutting carbon emissions, beating all projected targets. We became the country with the greatest offshore wind capacity in the world at a time when other nations didn’t recognise the necessity of investing in renewable energy.

We were placed at the heart of the European Union, which far from being a neo-liberal club was built and developed as a social democratic project, with its single market and the rights it affords crafted by socialist Jacques Delors as much as it was by Margaret Thatcher. It was the Social Chapter which had life-long Eurosceptics like Michael Foot and Barbara Castle converting to pro-Europeanism in the 1990s. It’s the genuine neo-liberals, steadily recognising the threat those safeguards posed to free-market fundamentalism, who have made Brexit their eternal ambition. It’s through EU membership and that progressive coalition on the continent that many of those once unwinnable battles have been won.

But perhaps the most baffling aspect of New Labour’s – Labour’s – legacy is that it still isn’t commonly recognised as the ethical socialist revolution it ultimately was. It’s easy to forget, in a period when ‘progressive’ Tories appear to be the rule rather than the exception, that rights for minorities and the basic freedoms we take for granted were once battles that hadn’t been won. David Cameron and Theresa May both supported retaining Section 28. Ann Widdecombe could have easily been the home secretary who defined the morals of a new millennium.

When the Tories returned after three successive defeats, they legalised same-sex marriage and accepted a socially liberal consensus that was by no means inevitable. It was a victory attributable to more than a decade of Labour hegemony and moving the public conscience leftwards enough to make social conservatism all but extinct.

We are one of the few countries in the developed world where such a revolution has taken place and it should never be overlooked or taken for granted how historic that was. Unlike the rest of Europe and America, what Blair once called ‘prejudice wrapped in a coat of reason’ has been utterly decimated as a coherent political movement.

There’s no equally radical promise in Corbyn’s Labour. And that’s the main point of divergence with past victories. It is not radical enough. Every successful incarnation of the party has achieved lasting change through pragmatism and an understanding of contemporary priorities. It’s not a desire to renationalise utilities that keeps me and my neighbours awake at night, but the same unresolved issues which led to Brexit in the first place. Fear that jobs won’t be available tomorrow in a world demanding skills that are currently unobtainable.

Strained public services and limited housing for which immigration was scapegoated rather than a lack of investment and reform. Unaffordable transport, which traps us in our towns and cities as stationary observers of decline, is in desperate need of innovative solutions rather than being reduced to a political football.

And it’s vital that the leader of the Labour Party champions a patriotic and internationalist vision of Britain as a progressive leader in Europe, rather than the indifference which allowed for that relationship to be distorted in the interests of the few. Grocery prices soar whenever Theresa May stutters through a speech and the pound stumbles. There are Leave voters – Labour voters – whose aspirations are reliant on a leader sharing difficult truths, which the party has never shied away from in the interests of the working-class.

Ultimately, Tony Benn was wrong to say that Labour isn’t a socialist party and Tony Blair was right to maintain ‘democratic socialist’ in the revised constitution. But what ‘socialist’ means in the context of the Labour Party doesn’t have a single definition and it certainly isn’t a dogmatically economic one.

Labourism is a much broader form of progressivism, which adapts to each era for the sole purpose of securing long-term power and making society fairer, equalising opportunity and improving the social conditions of the country for the most vulnerable.

That has always relied on building coalitions both inside the party and, more importantly, outside in the wider country. It’s not treacherous to stay true to that aim, but rather the greatest loyalty to the past and the future. Disregarding that reality for any other purpose – whether ideological or personal – is the real betrayal.

• Nathan Lloyd is a freelance writer from Liverpool and a member of the Labour Party