The release of Naomi Wolf’s latest book has been accompanied by much tumult after an error was pointed out in a radio interview. Here, she gives her account, and explains what she thinks is behind much of the vitriol.

Boris Johnson becomes Britain’s new prime minister at a time when Britain is reeling from resurgent forms of divisiveness. LGBTQ+ people, as well as other marginalised groups, are targeted by both leaders and the press in overtly hateful ways that many thought had been laid to rest.

For instance, Ann Widdecombe, the Brexit Party MEP, claimed that she believed in conversion therapy for homosexuals; her leader, Nigel Farage, rushed to her defence. News reports highlight parents protesting LGBTQ+ education in British school, and some UK newspapers showcase sustained transphobic attacks.

Is this hystericising of hatred of marginalised groups something new, or a tradition at times thoroughly well-established in British history? A recent twitterstorm, which centred on a new book of mine, brought this question concerningly to life.

My work, Outrages: Sex Censorship and the Criminalization of Love, focuses on prosecutions of men who had sex with men in 19th-century Britain, as well as on laws about censorship, crafted by the British state, at a time when it was extending its reach to suppress populations around the world.

These lessons from history – reminding us all that the British government (like the American) is never infallible, and that at any time human rights can be fatally occluded with disastrous consequences, even by respected members of parliament or of Congress – certainly have new relevance now.

My subject is a little-known hero of LGBTQ+ history, John Addington Symonds, a poet and literary critic. While working on my doctorate at Oxford, I came upon volumes of his letters. I was hooked: it was the voice of a young man caught between romantic attraction to other men, and an increasingly dangerous legal context for writers and for homosexuals.

Symonds, who was both courageous and cautious; his epistolary friendship with American poet Walt Whitman; and these restrictive British laws, are the heart of my book.

In the book, I erred in how I described two legal cases in 1859 and 1860. I misinterpreted the term ‘death recorded’ as executions, rather than as the lesser, but still serious, sentences involved. Dr Matthew Sweet pointed this out to me in an interview on his BBC Radio 3 show, Free Thinking, when I appeared on it in May. He had access to documents on a digital archive in 2017-18 that were not available when I did my own research.

Dr Sweet then asserted that “dozens” of executions I had mentioned, had not, in his view, happened. This exchange was widely picked up and reported on: “‘Several dozen executions? I don’t think you’re right about this,’ the host, Matthew Sweet, said, very politely filleting one of Wolf’s central claims” – approvingly, but erroneously, reported the New York Times Book Review, one of many UK and US news sites to cover the interview.

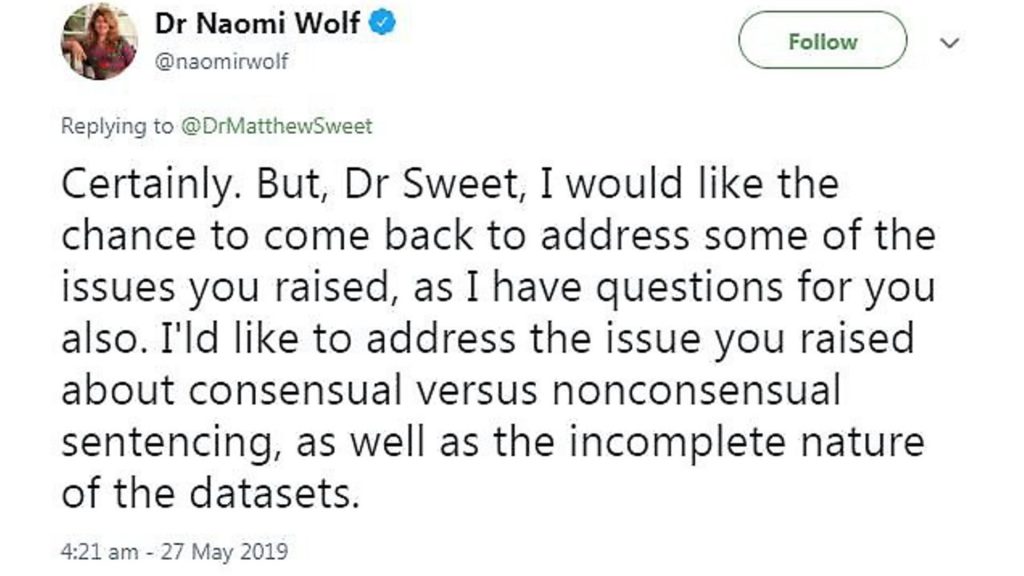

On Twitter, commentators built on this error of Dr Sweet’s – that I had erred on the reporting of “dozens”, rather than two, cases. Links to the interview were posted and people were invited to listen as I purportedly learned “on live radio” that the “historical thesis” of my book is based on a “misunderstanding of a legal term”.

The result was a Twitterstorm. A frenzied social media eruption then decided that my book was “debunked”.

The narrative that followed – that a prominent American feminist got “dozens” of executions, the “core” of my book, wrong, and was publicly chastised by a learned British man – was too delicious not to repeat. A huge initial wave, an average of 70 stories a day, often used emotive language: I was “humiliated”, “embarrassed”, even “mortified”, at being “called out” live, on “deplorable” errors.

The internet thought that all of this was hilarious; but virtually none of it was the case. Dr Sweet was right that two cases in my book had not resulted in executions. I thank him for the correction. But in other ways he was totally wrong. He insisted that ‘death recorded’ meant its “opposite” – the arrival of “a pardon”. The internet gave Dr Sweet (an expert on Victorian sensation novelist Wilkie Collins, as well as, according to IMDB, “a renowned expert on the television series Dr Who,” and not a legal historian) – full faith in his statement.

But scholars interpret this ambiguous term variously. Professor Robert Shoemaker, co-director of the Proceedings of the Old Bailey digital archive, stated that it means: “We won’t execute you if…” the prisoner serves a lesser but possibly still serious sentence.

Baroness Helena Kennedy, one of my legal readers, argued in the Independent, confirming Prof Shoemaker’s view, that ‘death recorded’ meant “a sword of Damocles” – that the prisoner could still be executed. Dr H G Cocks of the University of Nottingham, one of the most respected scholars of Victorian legal history and a specialist in the punishment of sodomitical offences, confirms, as the National Archives reveal as well, that in cases of prisoners sentenced to death for sodomy, some continued to petition for their lives.

In the Radio 3 interview, I twice issued stern warnings to Dr Sweet that his statement that I “would find” that “most” of the men sentenced for sodomitical offences in the 19th century, were child molesters or sexual predators, was not accurate.

Legal records used euphemism to describe same-sex sexual offences: as Dr Graham Robb, in Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century, Dr Charles Upchurch in Before Wilde: Sex Between Men in Britain’s Age of Reform, and Dr Cocks in Nameless Offences: Homosexual Desire in the 19th Century – all three among the most distinguished scholars in this field – confirm, the way that 19th century British laws lumped together rapists, child molesters and consenting adult lovers, is one of the ugly legacies of legalised homophobia. But my warnings about this solecism barely survive in the Free Thinking interview.

News outlets repeated Dr Sweet’s serious error suggesting that “dozens” of executions had not taken place – based on social media reports; none of the reporters had actually read the book or done their own primary research. Sadly, these executions are all too real.

Dr Upchurch confirmed British news reports of hundreds of arrests for offences involving same-sex contact; so did Dr Cocks; Dr Robb identified, as I mentioned, 55 executions before 1835. Dr Robb notes that as the death sentence for sodomy remained the law of the land until 1861, people lived, as he put it, in the shadow of the gallows.

Apart from the Guardian, I was not contacted for right of reply from any of the outlets – an omission that violates basic journalistic ethics; (the other violation of journalistic ethics is single sourcing. Let alone sourcing to a tweet).

Misreporting escalated. Emily Rutherford, a graduate student writing in PublicSeminar.org, invented from whole cloth a scene from Outrages in which I purportedly visited the London Library and claim to have rediscovered Symonds’ memoirs manuscript. This fictional scene was real enough to Rutherford that she assigns to it the cause of her throwing my book across the room. The problem is, none of this ever happened, and PublicSeminar.org had to issue a correction. But first, Dr Sweet and other reporters, including one at the New York Times, retweeted Rutherford’s essay, with its made-up scenario. Other erroneous reports came thick and fast; as did abuse from homophobic conservatives and from Nazi websites: “Jewish Feminist Lies about Fag Executions” read one white-supremacist website headline.

How did so many established news sites get so much wrong? If the ‘feminist humiliated on live radio’ story is trending (and it got up to 100% on Google Trends), then even if it’s largely wrong, algorithms will serve it up in different formats to news outlets; and editors will be more likely to sign off on versions of it, because it’s trending.

This generates more impressions, more clicks, and more money via ads. The accurate version of this story on the other hand – ‘scholar corrects scholar with a correction that is partly incorrect’ – is unlikely to have gone viral.

Vanished would have been this clickbait: alas, no humiliated feminist, no “dozens” of imagined executions, no “debunked” book, no titillating shame.

So whether the pressure is consciously felt by editors or not, news outlets have an incentive not to call the author for comment, not to look at the actual book, and not to make corrections.

These articles were not news or literary journalism, but gossip, conveyed in a tone often fuelled, I suspect, by gender bias. My errors of interpretation are not gendered and I take full responsibility for them. But the focus on my purported “humiliation” and its voyeuristic scrutiny of “how I feel” was, in my view, gendered.

I don’t believe that a 56-year-old male author of seven bestselling non-fiction books, one of which the New York Times called one of the most important books of the 20th century – who is also a former Rhodes scholar, a formal vice presidential and informal presidential campaign adviser, a recipient of Barnard and Oxford research fellowships, a former visiting professor in Victorian Studies at Stony Brook University, a former columnist for the Guardian, for George Magazine and for Project Syndicate, a reporter whose work appears in most major news outlets, a guest commentator on most networks, the CEO of a civic tech company with regular engagement from national political leaders (all of this comprising, of course, as the New York Times Book Review put it, in an equally gendered headline, “Naomi Wolf’s Career of Blunders”) – would be assigned a narrative framing involving a theatrics of emotionality.

My intention for Outrages is to give readers insight into this difficult history. I welcome public debate, especially since the wrongheaded journalistic consensus from a wrongheaded tweet about a wrongheaded early interview, has so seriously misinformed British as well as US audiences about tragic historical events.

I have asked several times to come back onto Dr Sweet’s show to question the host himself about some of the mischaracterisations in his version of history; but to no avail. Ultimately, though, none of what happens to me personally matters at all.

What matters is that the story of John Addington Symonds, which is so important to LGBTQ+ history, which is everyone’s history, gets to readers who want to know about it. And what matters is that Victorian LGBTQ+ history – and Victorian feminist history, which in my book is connected to it – not be erased.

Outrages isn’t a criminological table. It’s a love story; it’s also about how Symonds and his circle absorbed news reports of trials of men accused of same-sex intimacy, and about how these news reports generated fear. It takes few death sentences or sentences at hard labour to chill a civil society.

The ‘heart’ of my book and its thesis are intact. Unfortunately, many readers aren’t able to decide for themselves, as the US publication has been delayed, due in part, possibly, to this poorly sourced melee.

LGBTQ+ history is fraught with silencing and erasure, as are the histories of many marginalised groups. Investigations of this history should always be open to revision with new information. How many men who loved men were executed in 19th century Britain, how many were imprisoned, and for how long, should be a solemn inquiry about a painful, even bloody tragedy; not infotainment.

Symonds risked his freedom by telling his truth about love. By speaking nonetheless, Symonds helped bring about the freer future we all inherit. We should honour this early pioneer of the LGBTQ+ rights movement with rigorous debate and open inquiry; not silence him a second time, via a melee of lowbrow social-media spectacle, and lucrative misinformation.

This misrepresentation of history is especially regrettable in a time of weaponised, politicised homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of hatred, un-spooling disastrously for both of our societies, on both sides of the Atlantic.

– After this article was published the BBC provided this statement: “We’re unaware of any approach from Naomi Wolf to return to Free Thinking on BBC Radio 3, but would welcome her on should she wish to appear once the new edition is available.”

– You can listen to the radio interview here.