Music in Iran provides a challenge not just to the authorities but to our perceptions of the country, says Sophia Deboick.

Iran’s musical inheritance runs deep. It is the place where complex musical instruments first appear in the archaeological record (representations of lyres, harps and lutes dating to the third millennium BC survive), and the inherently rhythmic nature of Farsi, the centrality of the poetry of Hafez, Rumi and others to the cultural DNA, and the ubiquitous sound of traditional instruments like the santur (hammered dulcimer) and setar (Persian lute) have colluded to produce a deeply musical culture.

Yet, music has been the canary in the coalmine for freedom, as the country has gone through multiple cycles of censorship and clampdown which have sometimes resulted in wholesale bans. Over the years, Iranian music and musicians have become a focal point for the imposition of religious conservatism, the culture war against western influence, and the conflict between the generations (half of the Iranian population is under 25).

In the four decades since the 1979 revolution, music has been a channel both for resistance and officially-sanctioned values, and the capital, Tehran, is where that tension has been played out. A city with a similar population to London but less than half its size, Tehran is the beating heart of the country and a place of ceaseless activity and musical vibrance.

The story of Iranian pop began in the days of the Shahs. One of Iran’s most celebrated female singers, Qamar-ol-Moluk Vaziri, debuted at the Grand Hotel in Tehran’s own Roaring Twenties, sensationally appearing without a veil.

A radio star throughout the 1940s and 1950s, her mastery of the modal vocal repertoire of Persian music meant her work was highly valued by a culture with a sophisticated appreciation of the human voice as instrument.

By the time of Qamar’s death in 1959 Iran was experiencing its own rock ‘n’ roll revolution. A teenage Vigen Derderian, the ‘Iranian Elvis’, had moved to Tehran in the early 1950s where he was discovered by national radio. His debut, Mahtab (Moonlight), a western-style ballad sung in Farsi, ushered in a golden age of Iranian pop and signalled a break away from the traditional music of the past.

Vigen was well-placed to benefit from the reforms of the Shah’s White Revolution, from 1963 onwards, which saw an embrace of westernism, but in this ‘golden age of pop’ the traditional and the new existed cheek by jowl. Mohammad Reza Shajarian, master of the Persian traditional classical repertoire known as the Radif, emerged in the 1960s to become a national institution.

A popular performer and recording star, for three decades, his breathtakingly powerful Rabbana (Our Lord) – sections of the Quran sung to traditional Persian melodies – was aired on Iranian state media during Ramadan to mark the beginning of Iftar (the post-fast evening meal).

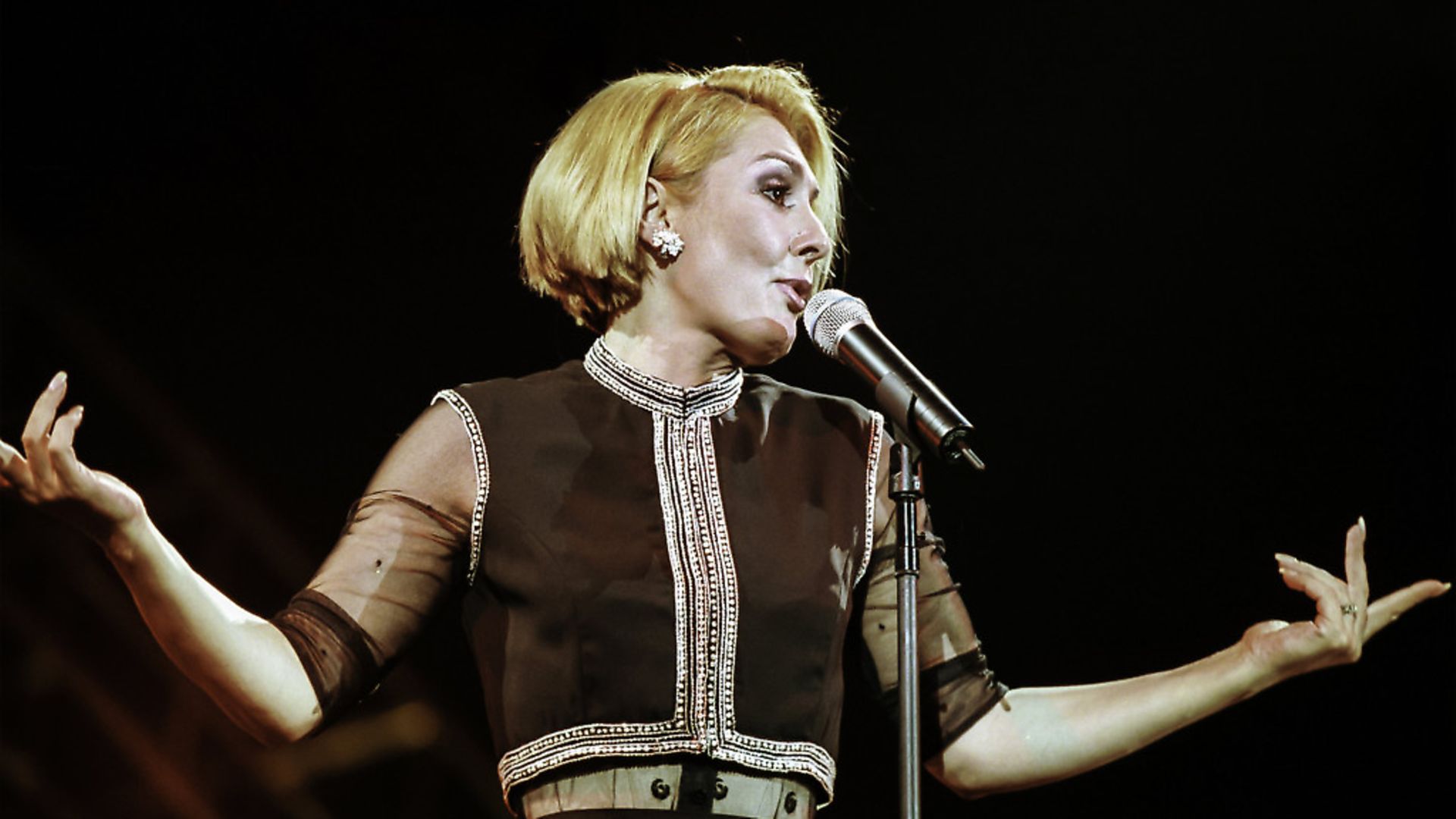

But this traditionalist shared the popular stage with pop starlets in the western mould. Born in a backstreet of the Karaj suburb of Tehran in 1950, Faegheh Atashin, known as Googoosh, released her debut album, Do Panjareh (Two Windows), in 1970, and her lush ballads and upbeat pop songs enjoyed huge popularity. She became the ultimate Iranian trend-setting celebrity.

When the 1979 revolution came, Googoosh was arrested and her records banned. Under the Ayatollah Khomeini, all concerts were prohibited, along with the broadcasting of music, and women were forbidden to sing as soloists in front of mixed audiences.

Seyyed Mohammad Javad Zabihi – a reciter of the Quran with a truly ethereal voice who was referred to as ‘the Shah’s singer’ – was dragged out of his house and murdered due to his links with the old regime.

Vigen’s wildly popular songs were banned and he died in exile in California a quarter of a century later. Many musicians fled and, out of the reach of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, known as Ershad – created in Tehran in 1984 to bring music under an official vetting system – Iranian pop flourished elsewhere, notably in LA.

Andy Madadian, known simply as Andy, and Kouros Shahmiri, both Tehran born and bred, recorded their chuck-away pop debut LP Khastegary (1985) in the US, before going on to successful solo careers there. The thousands of years-old story of Iranian music seemed to be over within its own borders.

While there was some relaxation of censorship under the presidency of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997), with Elton John, Chris de Burgh, the Gypsy Kings and Queen inexplicably among the officially permitted western artists, home-grown music remained constrained.

At the annual 10-day Fajr International Music Festival and Vahdat Hall, the city’s premiere concert venue and home to the Tehran Symphony Orchestra and Iranian National Ballet, the traditional and the classical have been officially privileged.

Emerging in the late 1990s, artists like the Tehrani, Alireza Ghorbani, an Iran National Orchestra vocalist and prolific recorder of albums of traditional Persian music, and Arian, a mixed-sex nine-piece pedalling slushy ballads and high energy Europop (the ‘Iranian Steps’ seems a fair description) have been uncontroversial, but appetites for a broader range of music have long fed a huge black market in pirated tapes.

Today, the impact of that illicit music is fully emerging, as a generation of musicians have taken those influences and, spurred on by the rise of the internet and the advent of Mohammad Khatami’s reformist administration in 1997, have created an underground music scene in Tehran of unsurpassed diversity and daring.

Rock band O-Hum, emerging in 1999 with their album Nahal-e Heyrat (1999), were early pioneers of Iranian alternative music. Blending disparate genres of western rock with traditional music, they couldn’t get Ershad approval, but a blind eye was turned to their concerts staged in Tehran’s orthodox churches as they tried to evade the system.

When Mahmoud Ahmadinejad declared a complete ban on western music just a few months into his presidency in late 2005, it was a sign of a new era of ultra-conservatism. But emergent Iranian hip-hop rose to the challenge. Tehran-born rapper Hichkas’ debut album Jangale Asfalt, produced by hip-hop visionary Mahdyar Aghajani, featured traditional Persian vocals and instruments along with lyrics that combined introspection and social commentary (“Ultimate jihad is against yourself, not other people”, as London-based rapper of Iranian descent, Reveal, puts it on Hichkas’ Dideh va Del).

Arrested for selling his CDs on the streets of Tehran without Ershad approval, Hichkas has since become another exile in London.

Tehran’s post-punk scene, brought to the fore in Bahman Ghobadi’s acclaimed film No One Knows About Persian Cats (2009), has also been riven by exile.

The pioneering The Yellow Dogs went to the US in 2009, and Hypernova, a four-piece formed in Tehran in the early 2000s, had already shipped out to the US by then.

Strongly Joy Division-influenced, their song Sinners was a stark comment on religious bigotry (“Burn you sinners, one by one/ You filthy, non-believing scum”).

Over the last six years, under the Rouhani presidency, the Tehran music scene has flourished, hosting a huge diversity of music, from the brutal experimental techno of Ata Ebtekar, known as Sote, to death metal band AtriA (probably the only band in Iran with a female drummer) and the Judas Priest-meets-Rumi stylings of Farshid A’rabi (his 2004 album Penhan (Hidden) was the first Ershad-sanctioned Farsi-language heavy metal album).

The north of the city hosts Café Paradiso, Tehran’s own rock bar, the self-explanatory Blues Café, and the Beethoven Music Shop, stocking CDs and vintage vinyl by both native and western artists.

But while much has changed in Iran – and the country’s first female MC, Salome, who emerged from the same Tehran hip-hop scene as Hichkas, says flatly on her Price of Freedom, from her ground-breaking 2013 album, I Officially Exist, “I do not have a rejection letter from Ershad/ I say no to any kind of supervision system” – Ershad does indeed still exist, even if permits are now easier to come by, and the government’s musical taste remains overwhelmingly conservative.

Yet, musical traditionalists and innovators have shown their differences mean little when it comes to defending their fellow Iranians. The violent crackdown on protestors in the wake of the disputed 2009 election that reinstalled Ahmadinejad saw the supporters of the Green Movement fill the streets of Tehran, the capital’s universities put on shutdown, and the Evin and Kahrizak prisons, on the city’s northern and southern outskirts, respectively, fill with prisoners. Between 36 and 72 people were killed.

Googoosh, her career revived after leaving Iran in 2000, protested at the UN, while Mohammad Reza Shajarian released Zaban-e Atash (The Language of Fire), entreating the Revolutionary Guard to “Lay down your guns” – his Rabbana was subsequently pulled from Ramadan broadcasts and hasn’t been used since. Other artists also responded through song, with MC Salome’s Don’t Muddy the Waters asking “If I stay silent, If I stay still/ Who is going to make it right?”, while Andy released a version of Leiber and Stoller’s Stand by Me with Jon Bon Jovi, sung in both English and Farsi.

But Iranian music has proved it doesn’t need to be political to be powerful. In the last 100 years, that music has been forged in adversity because that has been the story of Iran in the 20th century and, as Ata Ebtekar has remarked, whether it’s battling political oppression or Tehran’s infamous traffic, “Iranians are all about improvisation”.

Whether Iranian musicians have looked inwards and backwards, or outwards and forwards, as they improvise in order to create, all have started from the foundation of a rich cultural inheritance whose power is indestructible.