ALASTAIR SMART on an exhibition which cleverly pairs John B. Yeats, overdue a favourable reappraisal while Lucian Freud, is perhaps facing future reputational damage.

In October 1953, a benefit dinner was held at Jammets restaurant in Dublin for the octogenarian Irish painter, Jack B. Yeats. He’d fallen on hard times, and funds were being raised to buy him a new set of teeth. One of the contributors (although not there in person) was a 30-year-old Lucian Freud.

The relationship between the two artists is explored in a new exhibition called Life above Everything at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA). It features 33 paintings by Freud, 24 by Yeats, as well as numerous works on paper.

The pair never actually met. Freud first saw Yeats’ work on a visit to Ireland with his lover, Anne Dunn, after the Second World War (and got to know it better when the Irishman had a show at Tate gallery in 1948).

According to Life above Everything’s co-curator, David Dawson, “Lucian often spoke of how great he thought Yeats was. He admired his spirit, his originality, and the remarkable energy in his work”.

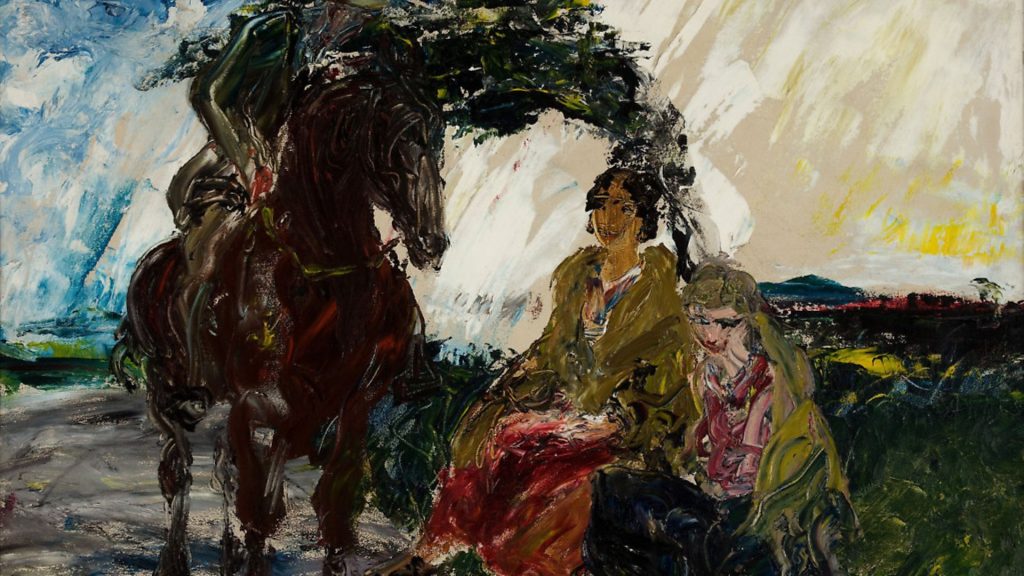

PLEASE NOTE: This image is protected by artist’s copyright which needs to be cleared by you. If you require assistance in clearing permission we will be pleased to help you. In addition, we work with the owner of the image to clear permission. If you wish to reproduce this image, please inform us so we can clear permission for you. – Credit: www.bridgemanimages.com

Given how scathing Freud could be about other artists, this was praise indeed. (He dubbed Leonardo da Vinci “an absolutely dreadful painter” and the work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, co-founder of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, “the nearest that painting gets to bad breath”.)

Having worked as Freud’s assistant from 1991 until his death in 2011, Dawson is now director of the Lucian Freud Archive. The IMMA exhibition was his idea and includes an early drawing by Yeats called The Dancing Stevedores, depicting a pair of dockers larking about on a gangplank before a large crowd.

Freud bought this work in the 1980s and hung it by his bed for the rest of his life. He was also known to recommend – and advise on – Yeats’ art to collector-friends of his.

The fact remains, though, that of all the artists one might have imagined being shown side-by-side with Freud, the Irishman comes pretty low on the list – if he makes the list at all. Francis Bacon would have been the most obvious candidate; then perhaps Frank Auerbach (like Freud, a Jewish refugee who escaped Nazi Germany for London as a child).

PLEASE NOTE: This image is protected by artist’s copyright which needs to be cleared by you. If you require assistance in clearing permission we will be pleased to help you. In addition, we work with the owner of the image to clear permission. If you wish to reproduce this image, please inform us so we can clear permission for you. – Credit: www.bridgemanimages.com

All of which makes the IMMA show so intriguing. Who even was Jack B. Yeats and what connected him to Freud? The first of those two questions is easier to answer. Born in 1871, Yeats was the younger brother of the poet, W.B. Yeats.

He spent his early life between Ireland and London, settling permanently in the former in his late thirties.

He found fame with romantic portrayals of everyday Irish life (such as A Lift on the Long Car).

His big stylistic breakthrough came in the 1920s, when he began to adopt loose, expressive brushstrokes and diffuse compositions. Samuel Beckett was one among many devotees, saying “Yeats is with the great of our time, because he brings light, as only the great dare to bring light”.

The artist died in 1957 and has, by and large, been forgotten in the decades since. Yes, work has done periodically well at auction (The Wild Ones became his first painting to reach seven figures, when it fetched £1.23 million at the Irish art sale at Sotheby’s in 1999). However, outside his homeland, Yeats is anything but a household name.

For Christina Kennedy, co-curator of the IMMA show alongside Dawson, “the exhibition is aimed at restoring his name… Specifically, in the sense of showing he was more than just an Irish painter. Yeats travelled widely in Europe – and we want to stress his place as an artist in an international context”.

Hanging his work beside that of one of the world’s most feted painters of recent times seems a smart way of doing this. Double portraits by both men appear, as do images of horses. But beyond similarities in their choice of genre or subject matter, the artists are united by what Kennedy calls “a sense of common purpose. Both were very individual painters, who resisted being part of any movement or school”.

Life above Everything isn’t the only major Freud exhibition of 2019: in October, the Royal Academy of Arts in London will stage the largest ever show of his self-portraits. Earlier this year, Phaidon also published a vast, two-volume monograph spanning the artist’s whole career – yours for the small matter of £395.

Talking of prices, the market for Freud’s work has been considerably strong for a while now. The record for a work of his at auction was set at Christie’s in New York in 2015, when Benefits Supervisor Resting, a naked portrait of the Jobcentre clerk, Sue Tilley, sold for $56.2m (£35.8m).

All of which is to say the artist’s star continues to rise. For his penetrating portraiture, he has even been compared by some critics to Rembrandt.

The interesting thing is, though, that for a large chunk of Freud’s career – from roughly the mid-1950s to the late-1970s, when figurative painting was deemed infra dig – he was as unfashionable as Yeats is now.

As late as 1987, there wasn’t a single museum in New York interested in hosting a British Council-organised retrospective that toured London, Paris and Berlin.

Reputations in the art world come and go, of course; they’re made and unmade. And one wonders if 21st century mores will soon catch up with Freud. Sittings for his portraits could be intense affairs – one subject, the painter Celia Paul, said she found it “an excruciating experience” and “cried most of the time”.

Right into old age, Freud had a voracious sexual appetite, too, seducing a host of female models, some of them as young as 16.

In Breakfast with Lucian, his tell-all book from 2013, Geordie Greig went into great detail about the artist’s sadistic streak with lovers. One of them was quoted as saying Freud “became quite vicious, he really hurt breasts and things”.

In the #MeToo era, can his reputation possibly survive intact? Only time will tell – though Freud’s champions will cite the fact that males, as well as females, were on the receiving end of his forensic scrutiny as a portraitist.

He didn’t spare himself in this regard either, as the 50 self-portraits at the Royal Academy this autumn will attest.

For the time being, there’s a fine show at IMMA to visit. What becomes clear from looking at the two men’s work together is that both enjoyed the sheer materiality of paint – yet the speed at which they applied it was very different.

“Yeats gives the impression of having painted in a flash, in one go,” says Dawson, “where Lucian worked very slowly, building up an image bit by bit. He loved the speed of Yeats’s brush, knowing full well he himself couldn’t paint like that.”

It’s as if Freud approached Yeats, then, as a fan much more than as a rival. The hope at IMMA is that the Irishman will have many more fans by the time their exhibition ends.

Life above Everything: Lucian Freud & Jack B. Yeats is on at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, until January 19, 2020