Jean-Pierre Melville’s recent work oozes sophistication and turns 50, JAMES OLIVER offers a retrospective.

There were those who said Jean-Pierre Melville’s films were all style over substance. Astonishingly, they seemed to mean it as criticism.

Few directors have ever controlled the presentation of their films so carefully, erasing the extraneous and obsessively refining what remained to build mood and attitude. When the style is this good, who needs ‘substance’?

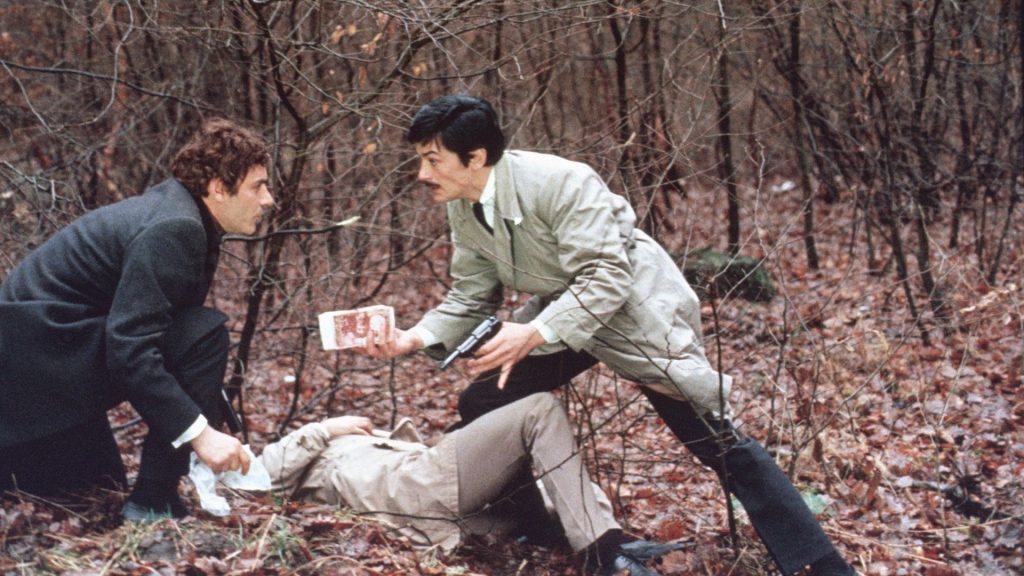

Le Cercle Rouge is one of the better examples of this. It turns 50 this year, hardly one of the major anniversaries of 2020 but one being celebrated with a fresh restoration and a new release that allows us to glimpse Melville at close to his considerable best.

It’s a long film – near enough two and a half hours – but the time rushes by, a blur of fedoras, trench coats and grim-faced men.

A plot that might have made for a routine policier in the hands of a lesser talent becomes something more epic thanks to Melville’s singular execution, a fatalistic dance of death.

There’s something else that needs to be stressed about Melville: his films were formed by his own compulsive movie habit.

He was the first of the great cinephile directors, whose work reflects (and reflects upon) cinema more than it does reality. Others would follow, some of them more passionate even than he. But, as we shall see, Melville exerted his own powerful influence on pretty much all of them

Born in 1917, he’d been a film fanatic since he was a tot, spending as much time in the cinema as he could, and watching things on a domestic projector when he was at home. He was called Jean-Pierre Grumbach then.

‘Melville’ was a nom de guerre, adopted as a tribute to the American author Herman Melville; Grumbach fought with the French army in 1940, was evacuated from Dunkirk and then returned to France to serve with the Resistance. Inevitably, it informed his own work both directly (he made three films about the occupation) and obliquely: the archetypal Melville character is a poker-faced loner possessed of the same self-sufficiency as those Maquis fighters who wanted to stay alive.

With the war won, he decided to follow his heart. But even national heroes weren’t going to get the red carpet rolled out for them by the hierarchical French film industry; if he wanted to direct, then he would have to possess his soul in patience and gradually work his way up through the ranks.

Well, screw that. After making a short film, he began making his first feature film in defiance of union rules (in those days, French directors needed to have a permit before they were allowed to say “action!”).

For his subject, Melville planned an adaption of a book for his debut, Le Silence de Mer by ‘Vercors’.

This was one of the major novels of the occupation, the story of a Francophile German officer billeted with a French family who decline to speak to him, the only resistance they could offer.

Filming it, however, faced at least one major problem: Melville didn’t have the rights. ‘Vercors’ – another nom de guerre by the way; he was really Jean Bruller – wasn’t about to gift his bestseller to a beginner with no money. So Melville

went ahead anyway.

Melville would make greater films but the mere existence of Le Silence de Mer (1949) is something of a triumph, a testament to Melville’s determination and focus.

Vercors recognised as much when he was presented with the finished film and finally gave the young man his blessing. The critics were just as impressed, noting how much Melville had accomplished with so little. It was even a decent-sized hit; certainly it earned Melville enough to pay the fine slapped on him for making a film without permission.

It would take a few films before Melville found his groove; he worked with the great Jean Cocteau, directing an adaption of the latter’s Les Enfants Terrible (1950) – by no means a bad film but one that owes more to its writer than its director – and undertook a solid, commercial project as a director for hire (Quand tu liras cette lettre [1953]) to prove to the film industry he wasn’t ‘an amateur’. It wasn’t until 1955 that he found his true metier.

Bob le flambeur (released in 1956) was Melville’s first excursion into the underworld. Bob is a gambler (a ‘high roller’, per some translations of the title), an ex-thief who still has an eye for a big score.

When he learns of the riches to be found in the safe of a Deauville casino, he decides to roll the dice once more.

It was undoubtedly influenced by Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), an earlier French gangster classic about a super-cool older criminal, even if it was conceived on a less expensive scale – where Touchez pas… boasted Jean Gabin, the epitome of French masculinity, Melville had to make do with Roger Duchesne, a former matinee idol (and Mike Pence lookalike) who had disgraced himself in the war. But the real star was Melville himself, finally coming into his own.

Heavily influenced by American crime flicks (as, indeed, are his characters…), Melville marshalled his limited resources brilliantly. So what if the budget was only one-tenth of the average French film of this time? He’d sacrifice sets and film in the streets, giving it an aesthetic halfway between Hollywood and realism.

This would prove tremendously influential on at least one group of viewers who recognised it as a liberation, a creative choice that brought new opportunities for movies, opportunities they were desperate to explore for themselves.

Flash forward four years, and Jean-Pierre Melville would have a cameo in a film made by one of them. This was A bout de souffle (‘Breathless’), directed by Jean-Luc Godard; it is, amongst many other things, a crime thriller that owes not a little to the styles pioneered in Bob le Flambeur. And that was hardly the only debt that Godard owed to Melville.

Like his friend François Truffaut (who’d made his own debut with Le Quatre Cent Coups the year before), Godard was able to start directing without a long apprenticeship, largely because Melville had already barged that door down.

He’d also shown that great films could be made inexpensively, as long as you didn’t mind leaving the comforts of a studio. Finally, there was the cinephilia: Godard, Truffaut and their buddies – collectively, they’d become known as ‘the French New Wave’ – were as passionate about movies as Melville. He’d shown them they didn’t have to hide it. They could draw attention to it on screen with homages and more. They could even make cinema their subject.

Melville was never of the New Wave – quite apart from anything else, he was always drawn to more commercial subjects than its directors were – but was happy to take credit as its John the Baptist.

He paid Godard the compliment of casting Jean-Paul Belmondo, star of A bout de souffle, in a number of films, firstly as a priest in Léon Morin, Pretre (1961) – another story of the occupation – and then, more memorably, as an ambiguous gangster in Le Doulos (1962), a career high for both men.

Le Doulos is taken from a crime novel of the same name (by Pierre Lesou) and boasts the best plotting of any Melville film, with a couple of sharp left turns that transform everything. But unlike many movies with a twist, it easily survives repeat viewings.

In fact it becomes, if anything, even greater once you know where it’s heading, with Melville’s stylisation seemingly commenting on the action, highlighting the inevitability that generic convention demands.

And that style was becoming ever more impressive. Although set (and shot) in Paris, the hoods and gangsters of Le Doulos drive big American cars, while the cops work out of an office patterned after one in an American movie (specifically City Streets [1931]). All the villains wear the trench coats and fedoras made famous by Humphrey Bogart as they would in subsequent Melville movies, more a dress code than practical necessity. The whole effect is utterly, ineffably cool.

Melville would refine all this yet further with Le Samouraï (1967), undoubtedly his finest crime film. Having fallen out with Belmondo, here he was working with Alain Delon, an even better fit for his preferred subdued approach.

Delon is allowed to do little in the way of emoting; he’s simply another element – like the colour palette, like the camera moves, like the editing – to be controlled by the director.

Delon is Jef Costello, a hitman. We see him prepare and execute – pun intended – another job, at a nightclub but we’re not the only witnesses. The club’s pianist (Cathy Rosier) got a good look at him too. But although given every opportunity, she declines to grass him up to les flics. The question of why she chose to shield him will decide Jef’s face.

It is a film about ritual, both the procedures that Jef follows before each kill – as precise and formalised as any Japanese samurai before battle – and the codes of genre that Melville feels obliged to observe. The film ends the only way it can – the way we knew it would – but it is still a surprise when it comes, and an oddly poignant one at that.

Melville’s next film would dial back the movie references. L’armée des ombres is – in every sense – his ultimate statement about the Resistance. It is also his masterpiece and amongst the greatest of all films, even if it has taken time for its merits to be fully appreciated.

When it was in first released in 1969, France was still processing the student uprisings of May ’68; a film about the heroism of the by-then conservative wartime generation was always going to attract youthful opprobrium and, sure enough, it was duly denounced as ‘Gaullist’ cinema.

Such criticism, however, reveals more about the political aftershocks of 1968 than it does the film, which is far from being any kind of triumphalist celebration of the resistance. The cell featured here – led by the very great Lino Ventura – fail in almost everything they undertake (they are far more efficient at killing their own than ever they are the invaders); acts of absurd bravery lead only to the Gestapo’s torture chambers while the ending… well, that would be telling but it’s not exactly calculated to get you bouncing Tigger-like out of the cinema.

It was a commercial disappointment at the time, which Melville blamed upon the more radical critics. Perhaps, though, he should instead have taken pride in attracting as many people as he did to such a bleak reminder of France’s humiliation.

Restored and re-released in 2005, it was finally recognised as his greatest achievement, most especially in America where uncomfortable parallels were drawn with what was then going on in Iraq.

The relative failure of L’armée des ombres sent him back to crime, first Le Cercle Rouge and then Un Flic (1973). The last is a troublesome film; Delon plays a tough, troubled, cop and Melville himself wrestles with a new modernity – criminals smuggle drugs rather than steal diamonds.

It contains some of his finest moments, most especially an opening robbery in a wintery Atlantic coastal town. But it is marred by its central heist sequence that invites derision with both its ostentation (a helicopter is involved) and the lamentable model-work (that helicopter really ain’t convincing).

Melville died soon after its release, from an aneurysm, aged only 55, with many more films still to make. But he his legacy endures. Appropriately for such a devout cineaste, he has become a touchstone for other directors; John Woo, Walter Hill, Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese have all tipped their fedoras to the maestro and that’s before you get to his indirect influence via the French New Wave.

Few filmmakers have ever distilled cinema so perfectly to its essence. You don’t need to be a film buff to dig these movies: Melville’s best work remains compulsively watchable, every aspect perfectly weighted to keep your eyes on the screen. Fashions may change but true style is timeless.

Le Cercle Rouge is released on blu-ray and UHD by Studio Canal.