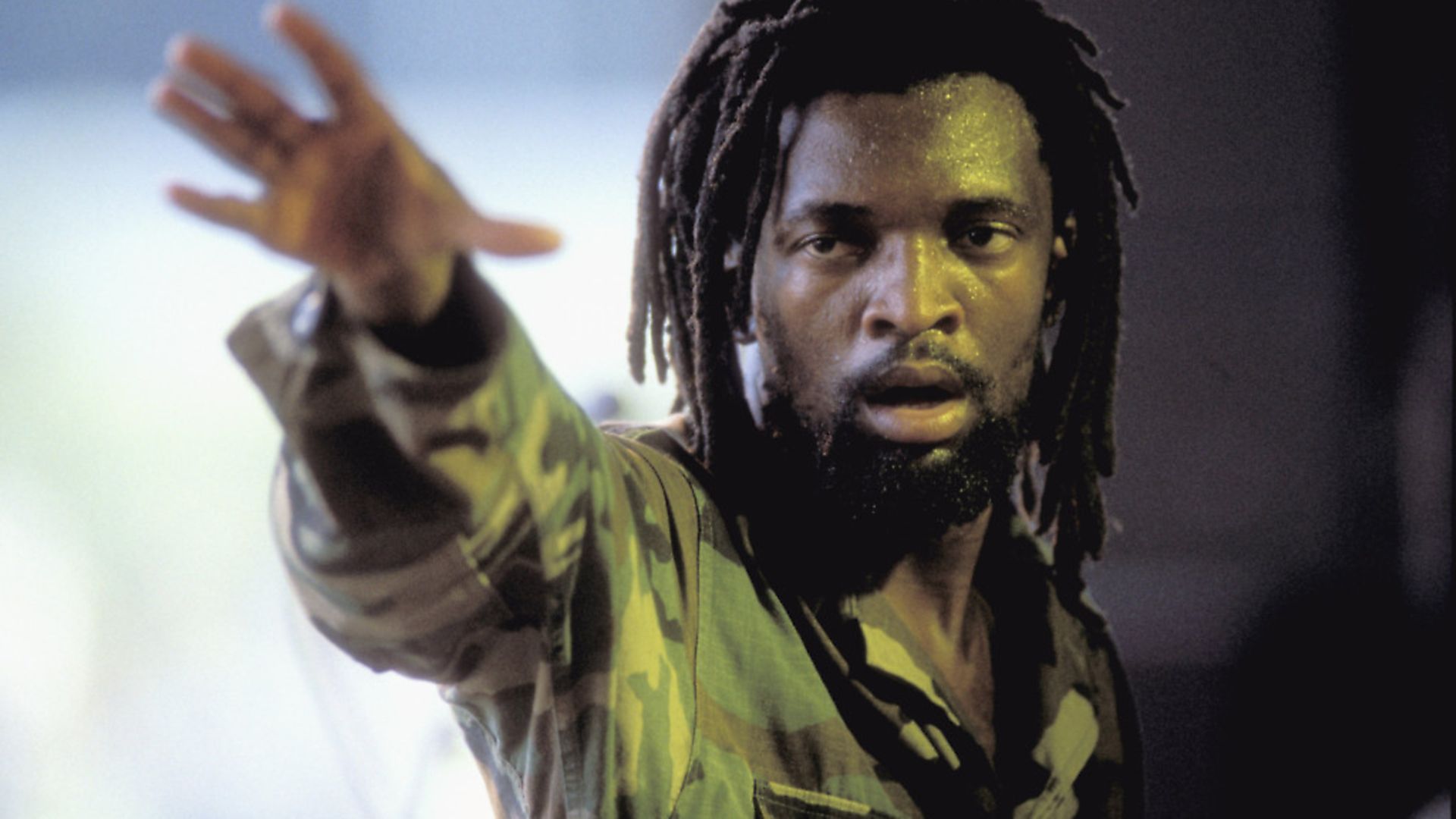

SOPHIA DEBOICK on Lucky Dube, the South African reggae star who made his life a mission, until it was cut tragically short

It was just one murder among thousands. The shooting of a 43-year-old man in a botched carjacking in a Johannesburg suburb in October 2007 was barely worthy of note given that 18,487 killings were recorded by the South African Police Service that year, a figure that itself represented huge under-reporting.

This was ‘a country at war with itself’, as the title of Antony Altbeker’s book of the same year put it, and in an atmosphere of rampant violence the man who had been shot twice and crashed into a tree in his desperation to escape could have been just another faceless victim.

But this was a death which sparked a massive outpouring of grief. The man who had died at the wheel was pioneer of South African reggae Lucky Dube, whose breakthrough album Think About the Children was released 35 years ago this year.

Twenty years after the violent murder at his Jamaican home of Peter Tosh – the man who Dube modelled himself on, with his socially-conscious yet life-affirming roots reggae, beguiling voice and energetic stage presence – history had repeated itself and, like Tosh, Dube’s death was devastating not just as a loss to music but for all he had stood for.

With his politically-charged lyrics, Dube had been a chronicler of the ills of South African society – substance abuse, family breakdown, violence and poverty – and an interpreter of the journey to a post-apartheid South Africa. And his death came at a time when feelings of national pride in this wounded country were running high – when the Springboks won the Rugby World Cup just two days after the killing, president Thabo Mbeki proclaimed that the national team’s win ‘must be a tribute to Lucky Dube.’

Dube was a man it was easy to admire. Spending almost a quarter of a century extolling unity and brotherhood in his lyrics, he also preached self-respect, rejecting drink and drugs entirely, and he did not accept religious dogma, instead fostering a personal spirituality which blended Rastafarianism with Zulu Shembe and the Zion Christian Church.

A father of seven who was more comfortable on his farm in the Kwazulu-Natal than on tour, his strong family values came from having an absent father and being raised by his grandmother in grinding poverty in the country’s rural east when his mother left to find work in Johannesburg, and Lucky Dube’s childhood could be mapped over the history of apartheid South Africa.

Nelson Mandela had just been sentenced to life imprisonment when Dube was born in August 1964, and South Africa had become a pariah state, banned from that summer’s Tokyo Olympics for fielding segregated teams. Dube’s younger years would encompass the assassination of prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd in 1966, the forcible resettlement of three million black South Africans to the ‘homelands’ in 1970, and the hundreds of deaths of the 1976 Soweto Uprising.

Dube had by then already been working as a gardener and groundskeeper for whites for many years and had had his own experiences of violence that never left him. An incident in which white youths set their dogs on him as a boy was frequently recalled by Dube in interview, standing as a symbol for the millions of individual incidences of white-on-black violence of the apartheid era. The year Dube’s breakthrough Think About the Children appeared, 1985, was the year the balance began to tip against apartheid, but South Africa was still a country on fire.

In March, 35 people were killed by police during a commemoration of the 25th anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre that had also seen police fire on demonstrators. In July, the government reacted to township uprisings by declaring a state of emergency and arresting the leaders of the anti-apartheid United Democratic Front.

This was a ripe environment for the messages about South African society Dube began to explore on Think About the Children, its title track a heartfelt plea for parental responsibility, but it was the more radio-friendly tracks like opener How Will I Know?, a sophisticated reggae ballad showcasing Dube’s impressive vocal abilities, which saw the album go platinum in South Africa and began to make a star of him.

In fact the success of Think About the Children hadn’t come from nowhere. Although still only 21, Dube already had seven records under his belt.

His first musical forays were in the Zulu-language mbaqanga style – the upbeat sound of the townships that had grown out of a marriage of American jazz and gospel to the local music in the 1950s and 1960s. Dube and his cousin Richard Siluma had taken inspiration from mbaqanga stars the Soul Brothers and formed the Love Brothers in the late 1970s and Siluma’s job at Teal Records, which later became part of South African recording giant Gallo, got them a foot in the door.

The two cousins released an album as ‘Lucky Dube and the Supersoul’ and Dube abandoned plans to study medicine to release five more mbaqanga albums between 1981 and 1987.

The covers showed a fresh-faced, enthusiastic Dube who was the very antithesis of his later serious reggae man image.

When Dube’s conversion to socially-conscious reggae came, it was not without consequences. Bob Marley’s 1980 concert in Harare celebrating Zimbabwean independence had been the alpha point for the arrival of reggae in Africa, and on the closer of 1984 EP Rastas Never Die, Reggae Man, Dube proclaimed: ‘Right inside of me/Deep down/At the bottom of my heart/Lies my secret/’Cause am a reggae man.’

Although there was nothing overtly political on the record, the South African radio censors were keenly aware of the dangers of reggae’s calls to freedom to their hegemony (the Moi regime in Kenya had just cracked down on reggae, after all), and barred the record from the playlists. Dube’s record company too were unamused – the EP sold only a fraction of what his mbaqanga records shifted.

But Dube felt he had a mission, and he had deliberately adopted reggae as it was an international language. He later commented ‘I wanted to reach the world. With mbaqanga I would have been seen as a tourist musician’. He went into the studio the following year and recorded Think About the Children without his label’s approval.

With this album Dube proved the domestic commercial potential of a uniquely South African reggae – one that incorporated African drums and the organ sounds characteristic of mbaqanga – before the follow-up, 1987’s Slave, showed it could also sell abroad. With a French release in 1988 and distribution deal with a US label, Slave sold half a million copies worldwide.

The changing face of South Africa over the next 20 years can be traced through Dube’s records. The title track of 1988’s Together As One was one of his greatest calls for unity and the following year’s million-selling Prisoner contained War and Crime, which pleaded ‘Why don’t we/ Bury down apartheid/Fight down war and crime’.

But Prisoner’s title track was devastating, lamenting ‘Somebody told me about it/When I was still a little boy/ He said to me, crime does not pay/He said to me, education is the key’, before offering the counterpoint: ‘The policeman said to me, son/They won’t build no schools anymore/All they’ll build will be prisons, prisons.’

Dube’s smooth reggae grooves often jarred with the bleakness of his lyrics which reflected a depressing reality.

But as apartheid was slowly dismantled, Dube remained a realist, if not quite a cynic. While House of Exile (1991), appearing the year after Mandela was freed, included Group Areas Act, which celebrated the repeal of the urban segregation law, the track Mickey Mouse Freedom reflected on how post-independence African states still suffered ‘corruption’ and ‘starvation’ – would post-apartheid South Africa go the same way?

Album track Crazy World reflected on the continuing violence, and Dube was not in a much more hopeful mood 10 years and five albums later, the Soul Taker LP finding him saying ‘The world knows your people as/The most violent in the world’, asking Is This Freedom? in light of continuing inequalities, and dealing with the AIDS crisis on Sins of the Flesh.

But for all its rootedness in the black South African experience, Dube’s music was making an increasing impression abroad throughout this period, attracting roots reggae purists at a time when dancehall was taking over.

In 1991 he was the first South African artist to play Jamaica’s Sunsplash festival. Dube silenced critics who saw African reggae as inherently inauthentic, impressing the crowd at this iconic event at the home of reggae so much that he played a lengthy encore and was back the following year in a headline slot.

Dube opened for Peter Gabriel on his Secret World tour in the summer of 1993 and in 1995 he became the first South African to be handled by Motown, the label putting out his Trinity LP. The same year he performed at the Albert Hall in The African Prom, and the release of the British label the World Music Network’s Rough Guide compilation of his work in 2002 was confirmation that he had cracked the West.

But Dube would also reach some of the most remote parts of the world. When he did a short Australian tour in 2005 he found he was already an icon to many indigenous Australians who identified with his lyrics about racial oppression, and he had already influenced the Aboriginal desert reggae of the likes of the Tjupi Band and Spin.FX. His Alice Springs concert came to be remembered as legendary in those communities, and an appearance at the Live 8 concert in Johannesburg in July also made 2005 a special year.

But Dube’s intention to write ‘music that reflects our daily experiences [in South Africa]’ but ‘talks to people of the world’ meant he always returned to the concerns of his homeland, and he said of Monster from his final album Respect (2006): ‘Even though in the past we had that apartheid monster that died… we didn’t change the peoples’ minds. So now that is the next thing that we have to deal with: the people’s minds now.’ His mission was far from over when his life was cut short on that suburban street.

Dube’s legacy runs deep. While inevitable comparisons have been drawn between him and figures like Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, his contribution to reggae was unique. While his lyrical outspokenness and vocals were indeed modelled on Tosh, he had his own ideals. Tosh sang Legalize It (1976), while Dube was stridently anti-marijuana. Tosh toted a guitar shaped like an M16 assault rifle and emphasised justice over peace, but Dube was all about reconciliation.

While Marley’s lyrics drew on the all-encompassing salvific worldview of Rastafarianism, Dube wrote without dogma and on the less exalted plain of personal experience. And that was the point. In plucking the political intent of Jamaican reggae by the roots and planting it in the soil of apartheid South Africa, Dube disrupted the idiom.

As scholar of the African diaspora Louis Chude-Sokei has shown, reggae had idealised Africa as a utopia – the paradisiacal motherland of Zion from where ancestors had been torn by enslavement – but Dube was rooted in the reality, highlighting the suffering in a part of the continent where ‘Mama Africa’ was livid with distress and where the oppressive white society of ‘Babylon’ of Rastafarian belief was found in its starkest, most appalling form.

Marley and Tosh may have sung in support of the liberation of African states, but it was not from a position of first-hand experience. Dube sang it because he had lived it and he gave roots reggae a new life in the process.

As the three carjackers convicted for Dube’s murder serve their life sentences, his music lives on, not least through the music of his daughter Nkulee, who was with her father when he was attacked and is the spit of him. As Dube put it in his song Reggae Strong (1989), one performed by his Slaves backing band at his memorial service: ‘They tried to kill it many years ago/Killing the prophets of reggae/But nobody can stop reggae/’Cause reggae’s strong.’