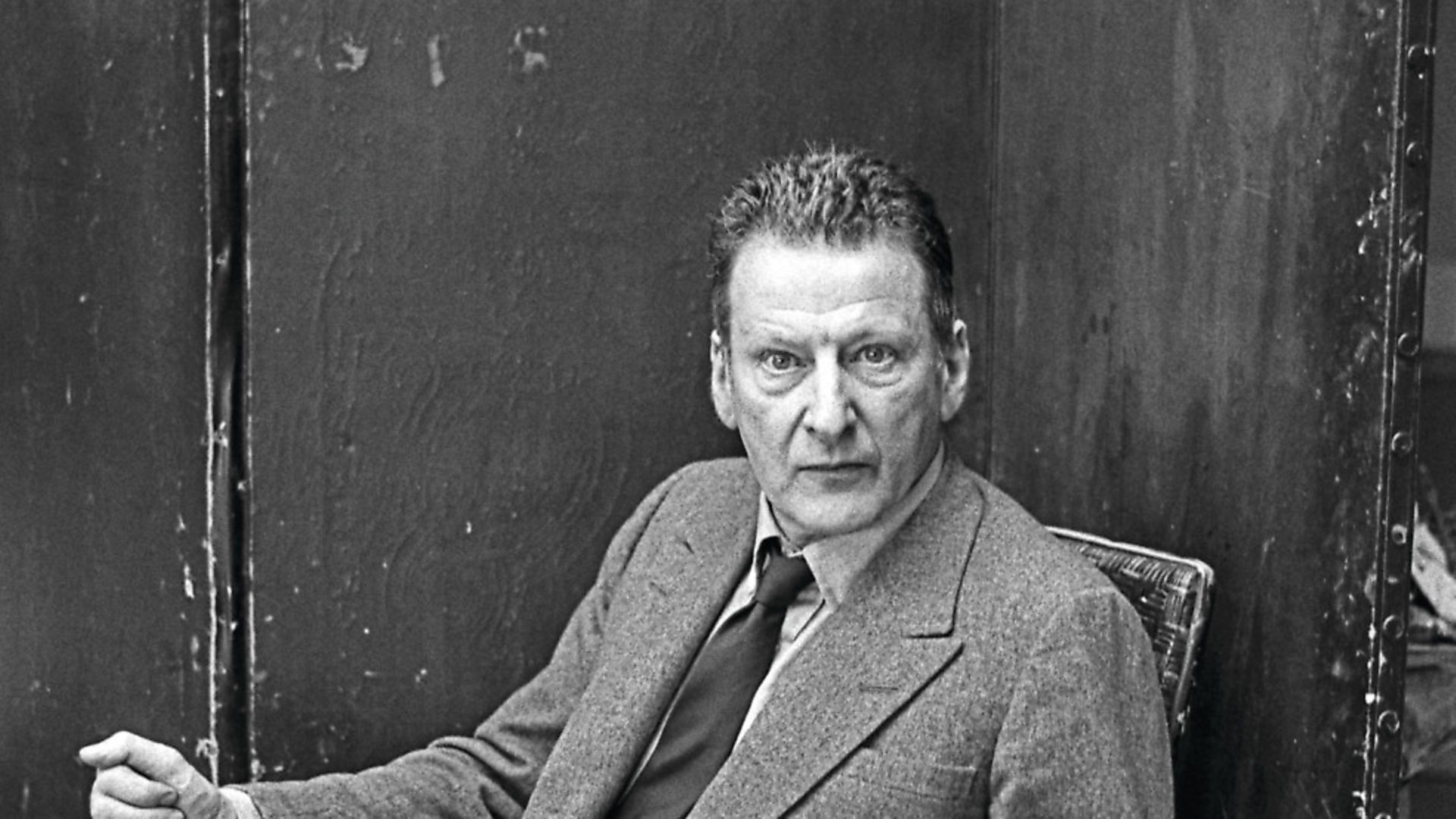

Lucian Freud was more than just one Britain’s finest ever artists. Here ADRIAN BURNHAM explores an artist that pursued his subjects like quarry

A new play by Toby Franks joins the countless efforts of writers, journalists, art critics and scholarly types who have sought to portray the man and make sense of the work of artist Lucian Freud.

I’m going to pitch in with a punchy line, one that’s arguably too personal, usually irrelevant and always unfair: yes he was a demon painter of dog fur and décor but Freud was all about the captivation of flesh.

While pursuing people – who he liked to consider as animal – the artist showed not a hint of reservation or embarrassment in his venery, that lifelong mission to capture, to ‘chase down’ – both in paint and in real life – his own but mostly other people’s bodies.

Writing two years after Freud’s death in 2011 then Evening Standard editor Geordie Greig effused: ‘His pictures sent a chill down the spine … He was fearless, even in his early eighties getting into a fight in his local supermarket in Notting Hill. He hung out with gangsters in the Sixties, borrowing money from the Krays. It was an offer he wished he had refused as they were not exactly willing to wait to get their cash back. He was occasionally on the run from the police. He had gambling debts running into the millions. And always he was on the hunt for women, to paint, to seduce, to be part of his life.’

‘A painter must think of everything he sees as being there entirely for his own use and pleasure,’ so Freud wrote in 1954.

An artist friend who, in his younger days, was similarly led by ‘a legendary libido’ once told me a tale about Freud. Keen to check my facts I texted him: ‘Pete, did Lucian Freud try to shag you or did I imagine that one?’ A response pinged back almost immediately: ‘Yes he did, but he was casual about it. Apparently he could be quite forceful sometimes. X’ So Greig’s ‘lover, fighter, gambler, monster, genius’ didn’t always take hold of his prey.

And in life, so it was with his art, Professor Sir Ernst Gombrich in Art and Illusion quoted the artist (‘One of the most original young painters in England’) on the elusive nature of Freud’s perpetual need to chase: ‘A moment of complete happiness never occurs in the creation of a work of art. The promise of it is felt in the act of creation, but disappears towards the completion of the work. For it is then that the painter realises that it is only a picture he is painting. Until then he had almost dared to hope that the picture might spring to life.’

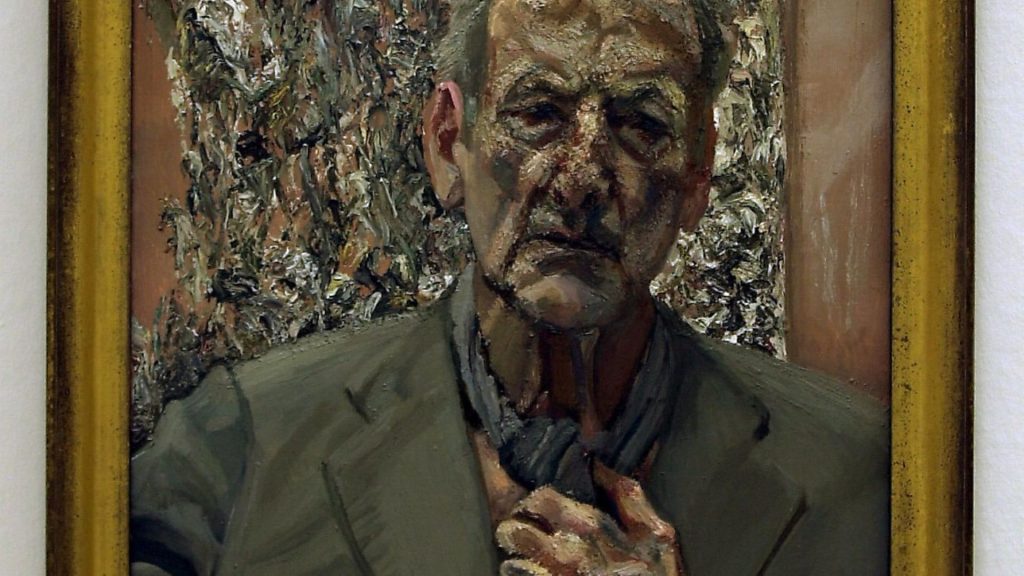

If, for the moment, we confine our interest in Freud to his art, obviously he is known first and foremost for forensically observed paintings of the figure. Up until the mid to late 1950s they featured family, friends and lovers rendered in painstaking detail, self-portraits and striking looking women with somewhat exaggerated features and sparse but significant props, they are stylized and enigmatic depictions of psychological tension.

Girl with Roses (1947-48) is typical, it’s a painting of Freud’s first wife Kitty Garman. Sitting on a rattan-backed chair against a mustard coloured wall, the arabesque of the chair arm contrasts with the sitter’s rigid pose. Resting on the folds of her charcoal skirt is a stumpy stalked rosebud and Garman’s pale white hand. Her other hand is held up in front of her chest, clutching a longer, razor thorned stem with another yellow and raw red bloom aglow against her dark sweater with moss green stripes. Garman’s expression is alert, her lips very slightly parted as she stares fixedly at something or someone off to her left. The more I look at the work, the more unsettling it becomes. There’s something oddly haunted or even funereal about it.

Another painting in the British Council collection, made more than twenty years after the portrait of Kitty Garman, is Naked Girl with Egg (1980-81). Bold, painterly mark-making in this work exemplifies the artist’s later more fluid and impasto use of paint. There’s still an unrelenting scrutiny on Freud’s part but in the late 50s a shift from sable to hog hair brushes and the choice of Krems over flake white lent Freud’s flesh a much more luminous quality. Also the compositions of his later works are more awkward, less formally staged, it’s as if we’ve happened across the naked subject in a fleeting, never altogether comfortable moment.

The young model in Naked Girl with Egg – artist Celia Paul, who Freud met when teaching at the Slade in 1978 and who later became his lover and gave birth to his son – is lying prostrate on a crumpled black coverlet. She’s supporting the weight of one her breasts while the other flattens and sags to her side. Her expression is pensive and there’s something reticent about the way she holds a hand to her reddened face. In the foreground her knees appear huge. This in part due to the fact that during his mature period Freud chose to paint standing up. The viewer is put at a vertiginous angle. The model’s lower limbs appear large because we’re leaning over them, they’re almost within touching distance. And in the immediate foreground two halves of a hardboiled egg nestle in a grey-white dish. The table or tray they’re on appears abstract, flat, almost parallel with the picture plane. The incongruous egg halves both amuse with their yellow googly eyes but at the same time bring to mind George Bataille’s characters’ lewd, sexual egg play in L’Histoire de l’oeil.

So, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the figure was Freud’s abiding inspiration but this isn’t the whole story. What Freud was excited by above all was the atmosphere created between people: himself and the object of his ravenous gaze. ‘The effect in space of two different human individuals can be as different as the effect of a candle and an electric light bulb. Therefore the painter must be concerned with the air surrounding his subject as with that subject itself. It is through observation and perception of atmosphere that he can register the feeling that he wishes his painting to give out.’

Having attended Camberwell School of Art and therefore to an extent trained in approaches and concerns associated with School of London artists I was instinctively drawn to the later works rather than Freud’s earlier, tighter, more graphic paintings. They chime better somehow with Freud’s legend: his protean desire, will to paint, that constant hunger. There’s an always searching quality to them, it’s in the innovation, variety and apparent speed of the mark-making, the precarity and peculiarity of poses, the effort to fix a ‘whole emotional attitude’, to make something so intangible into a material object using the ancient medium paint, to arrive at what critic Adrian Searle called Freud’s ‘perverse depictions of magnificent muck’.

In their time Freud’s paintings shocked and fascinated in equal measure. An argument could be made that he along with contemporaries such as Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff challenged the restrained and idealised nudes of the Academy. That the Second World War tore a rift in some aesthetic continuum demanding new modes of seeing and creating. But another story of art would see Freud’s continuing, in terms of mindset and modus operandi, and being firmly indebted to modernist painters from Paul Cezanne to Chaim Soutine.

What do the paintings mean now? It would be tempting to say, given the ludicrous sums being paid for Freud’s work – Benefits Supervisor Resting (1994) sold for more than £35m in 2015 – that the paintings’ visual presence has been overshadowed by their becoming financial assets, objects that more than anything else index and harbour wealth, investment. But that would be an overly reductive point of view.

Reviewing Breakfast with Lucian (2013) Greig’s gossipy biographical enterprise – that both offers an understanding of Freud but at the same time hawks the kind of myth-making that can stymie enquiry – Frances Spalding concludes with a quote from Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice: ‘Who shall unravel the mystery of an artist’s nature and character! And who shall explain the profound instinctual fusion of discipline and licence [dissoluteness] on which it rests!’

We’ll never know a full and final answer because, of course, there isn’t just one answer. All we as viewers can do is make an assessment of Freud the man and his work from as wide, thoughtful and informed a consideration of the ‘evidence’ as possible. I’m looking forward to Looking at Lucian, Toby Frank’s new one man play starring Henry Goodman, to see what more we can glean about Freud, a man who embodied such serious and vexing extremes.

Adrian Burnham writes on art and urban culture. He is founder and curator of www.flyingleaps.co.uk a street poster and web platform for artists. Email him at info@flyingleaps.co.uk

Looking at Lucian is at the Theatre Royal Ustinov Studio, Bath (01225 448844), to September 2