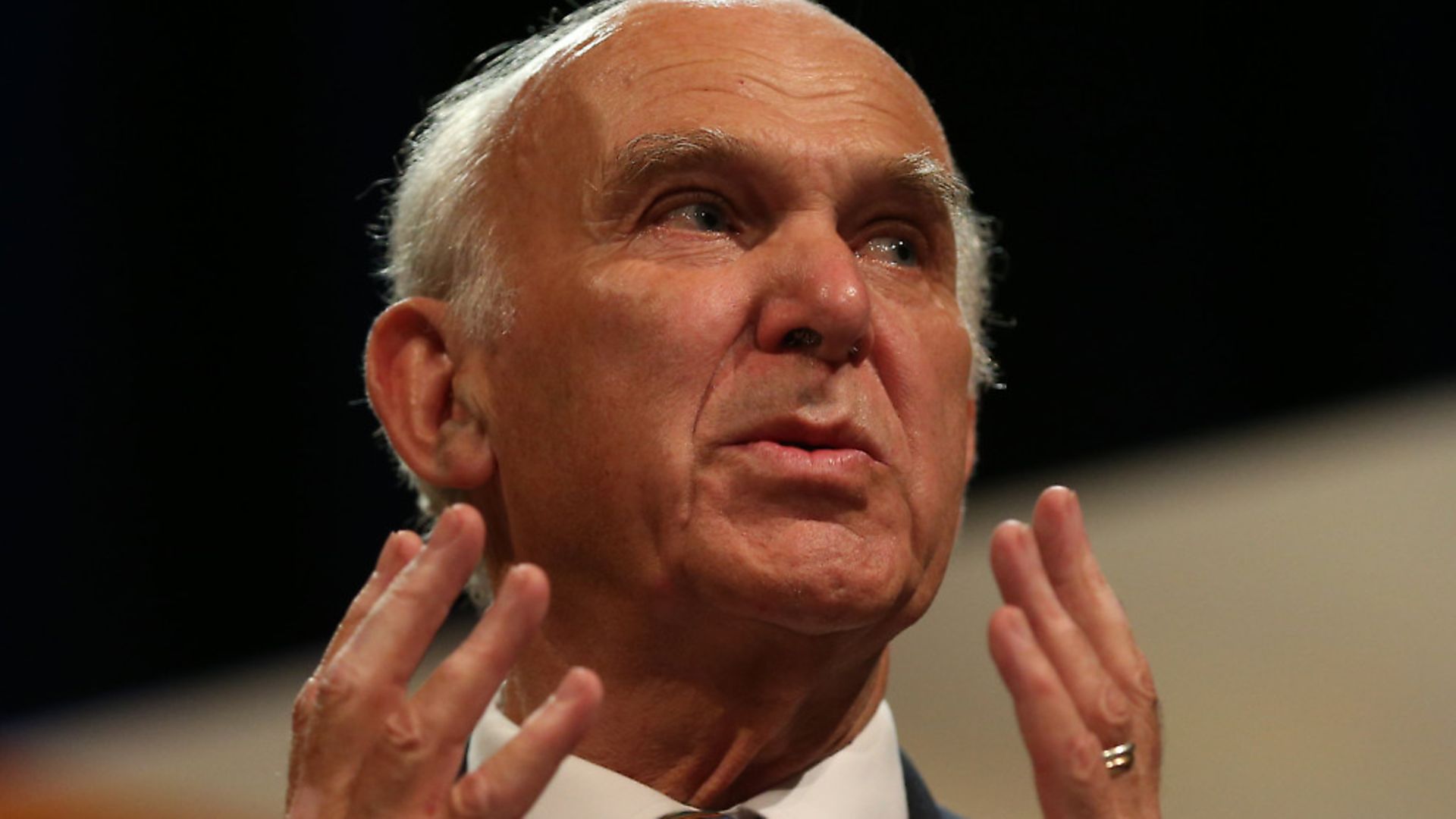

With disaster looming, Liberal Democrat leader VINCE CABLE explains how best to exit from Brexit.

Brexit has become a long, draining, war of attrition: the EU negotiating process is not due to be completed until the autumn of 2018 at the earliest.

It could drag on for years beyond that. The debates in parliament are becoming seriously repetitious even though they have barely begun, while the prolonged disruption to the normal business of government is sucking energy and precious resources out of everything else.

Eighteen months since the referendum and three months after serious negotiation and legislation began, what is happening on the battlefield? Several interim conclusions can be drawn.

UK public opinion has remained highly polarised and, mostly, entrenched, though there are some potentially significant shifts.

There has been some sign of a move to Remain, a belief that leaving the EU is a mistake, though that shift isn’t, yet, sufficiently big or sustained to challenge the fundamentals of negotiation.

The public has definitely become disillusioned with the government’s performance: the sight of ministers divided among themselves – a disunited team of one versus a united team of 27; the lack of preparation; the fiasco of the impact assessments which weren’t; the veto exercised by a Northern Ireland party which represents only 1% of British voters and only a minority of Northern Ireland referendum voters.

All this has fed disillusionment and frustration.

Realising that this is their Achilles heel, the Tory Brexiteers and their friends in the press have taken to presenting even the most trivial accomplishments – like the launching of the ‘blue’ passport – as a triumph of national will and negotiating brilliance over dastardly foreigners in the face of Herculean odds.

Despite these antics, or perhaps because of them, there is now a clear and growing majority in favour of giving the public a vote on the results of the negotiation, according to Survation.

British public opinion may be responding also to the underlying dynamic of the negotiation: that Britain has very little bargaining power and is largely responding to, and accepting, the conditions set out by the EU 27.

The central proposition is that a departing country cannot continue to enjoy market access (to the single market) on the same basis as existing members unless it commits in full to the acquis (all the rules and obligations, without ‘cherry picking’: that is, the ‘four freedoms’ plus the payments to the EU budget and restraints imposed on state aids, government procurement and competition policy in the interests of ‘level playing fields’).

We have yet to see the way trade negotiations will play out. But the financial settlement gives us a flavour of what is in store.

The financial settlement essentially is based on a formula close to what the EU Commission proposed originally and is a long way from telling the EU to ‘go whistle’.

A UKIP leaflet delivered to my home over the Christmas period tells me what hard core Brexiteers think about the settlement: a ‘betrayal… she hasn’t got anything in return’.

Indeed, the government, unconditionally, without so far achieving any agreement on market access, will pay around £50 billion in the form of outstanding (net) obligations and the equivalent of over five years’ contributions, with potentially more to come.

The key issue for the next stage of negotiations will be about how much market access can be achieved for British exporters beyond that available to a country with no preferential arrangements with the EU (like the US or Brazil) or very limited preferences mainly related to tariffs (as with Canada and Japan).

Either approach would represent a substantial degree of disengagement from the EU because 30 years of close integration have essentially been about regulatory convergence.

We have been promised that there will be ‘pluses’ to add to a Canada-type deal but in practice these will relate to matters like defence and intelligence cooperation and will, very probably, exclude anything of real value for the services sector (which is 80% of the UK economy) and financial services in particular.

The UK could, of course, ask for Norwegian-style single market association but the government is quite adamant that it will not, since that entails a commitment to free movement. It could also choose to remain in the customs union which would be of great value to our supply chain industries and avert a confrontation over the Irish border. But it says it will not go there either.

The most likely outcome is that the government will end up with a very weak agreement which would have been rejected out of hand as a ‘bad deal’ a few months ago.

Great efforts will be made by the Brexiteers and their allies in the media to spin it out as a triumph (which for them it is: Brexit is an end in itself).

The EU may play along with this narrative to get rid of the Brexit problem and to avert a confrontational ‘no deal’.

Parliament will find it difficult to exercise a scrutiny function since there will be little to scrutinise beyond a ‘heads of agreement’ leading to a period of transition. And any vote on the final deal in parliament will be decided largely on tribal lines rather than on the merits of the issue.

The Labour Party leadership will go through the motions of criticising but, as we have seen already, they have little interest in resisting Brexit as opposed to reaping the party political benefits of failure.

Brexit as currently envisaged is potentially a disaster for the country and not at all what a majority of the electorate voted for in the referendum.

So, what is the way forward (or out?)

Whatever reservations many of us have about referendums as a way of making big decisions on complex national issues, it is the only satisfactory way to proceed.

The public seem to think so, too. That is why I and my party will double down on the principle of letting the people decide on the eventual deal with the choice of adopting that deal or making an ‘exit from Brexit’.