For good or bad, most of the parallels drawn with the Labour leader have been with Tony Blair. But, says PETER KERR, perhaps he is most like the man Blair defeated.

Back in April, George Galloway quipped that Keir Starmer is ‘Tony Blair without the laughs’. Putting aside the dig at Starmer’s humourless persona, the comparison between the current Labour leader and the party’s most successful former PM is one we’re likely to hear more often.

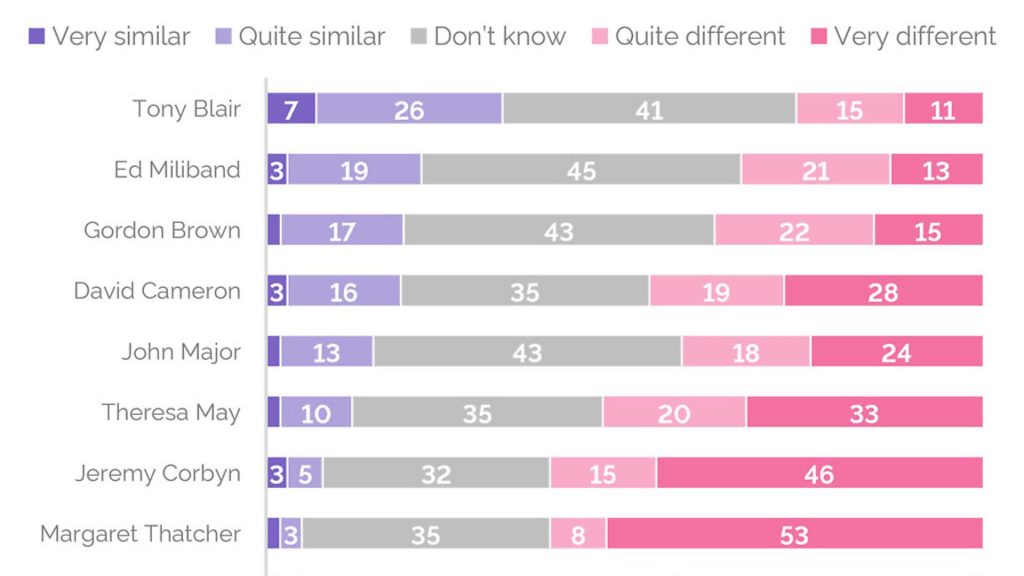

Indeed, a recent YouGov poll, taken 100 days into Starmer’s time as Labour leader, showed that a third of UK voters compare Starmer to Tony Blair.

An earlier poll, conducted in June, showed that Starmer is, in fact, the most popular Labour leader since Blair, putting the current leader’s approval ratings on a par with Blair’s in December 1994, shortly after he became leader of the opposition.

These comparisons will undoubtedly strike a chord with both sides of the Labour party.

For the moderates, it will ignite their faith that Starmer can emulate Blair’s achievements in pulling the party out of its electoral wilderness and, indeed, the clutches of the left.

For the Corbyn loyalists, it will undoubtedly fuel their suspicions that Starmer’s aim is to purge the legacy of the Corbyn project and take the party back to its Blairite past.

But is the comparison between Starmer and Blair a valid one?

Certainly, there are some obvious parallels. Like Starmer, Blair’s main task was to restore the electability of the party after a long period in opposition.

And, as we’re starting to see with Starmer, Blair approached this challenge by signalling to the electorate, the media and business interests that he was pulling the party towards the centre ground of politics and wrestling control from the trade unions and the left.

‘Socialism distancing’ as one social media meme recently put it. In this respect, Starmer perhaps faces a bigger challenge, as much of Blair’s work had already been done for him by his predecessors Neil Kinnock and John Smith.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that Starmer’s generally amiable persona as a sensible and moderate centrist places him much closer to being a Blair-like figure than a committed ‘Bennite’, like his predecessor, Corbyn.

Yet, in these early days at least, this is where the comparisons potentially end.

For it would be a mistake to misremember the younger Tony Blair of the mid-1990s as a being merely a ‘sensible’ or ‘dry’ centrist – labels which could easily be applied to Starmer. In fact, Blair’s major success was in projecting himself as a charismatic leader offering something distinctly ‘new’ to British politics.

This sense of newness was encapsulated by his ‘modernisation’ rhetoric – a rhetoric which allowed him to claim that he was not just in the business of modernising his party, but also the wider UK government and economy.

All of which allowed him to project himself as someone who harkened more to Labour’s future than to its past.

Of course, there’s a huge extent to which this projection of ‘newness’ and futurity from Blair was largely smoke and mirrors, given the extent to which the former Labour leader ended up following a path laid out by his predecessor Margaret Thatcher.

Yet love him or loathe him, much of Blair’s early electoral success lay precisely in his ability to convince voters that he was offering something fresh and distinct from both his Labour and Conservative predecessors.

Starmer can credibly claim to be offering something different to Corbyn. He has also been widely lauded for offering a contrasting style to Boris Johnson. His more serious persona and forensic eye for detail both help make him look like the adult in the room when the two go head to head.

Yet are these qualities enough to convince voters that Starmer is offering something substantively new?

What Blair brought was a distinctly new political lexicon; a language built around notions of modernisation, third way ideas, stakeholder capitalism, and the need to overcome social exclusion, embrace globalisation and create joined-up systems of governance.

These discourses of newness, transformation and future vision were powerfully employed through a range of innovative marketing techniques.

The result was the emergence of New Labour as a ‘project’ built around the personality of its leader, and one which promised to have the transformative potential of its predecessor project, ‘Thatcherism’. In those respects at least, it is Corbyn rather than Starmer who begins to look a bit more like Blair.

There are, of course, endless criticisms that can, and have been, made of Blair’s time in government – not least that his main legacy was a loss of up to five million Labour voters following the fall-out from the Iraq War.

There is a strong argument to be made, even from a centrist position, that Starmer would be wise to avoid any such comparisons with Blair.

Yet, there are nevertheless key lessons that the current Labour leader might want to take from Blair. Foremost is the need for Starmer to forge a broader ‘vision’.

Where does his own claim to ‘newness’ lie, other than the fact that he’s a grown up? What languages and slogans might we identify as Starmer-esque?

And where, as Galloway pointed out, are the laughs? Where is the charisma and the carefully fashioned ‘brand’ that Starmer wants to project?

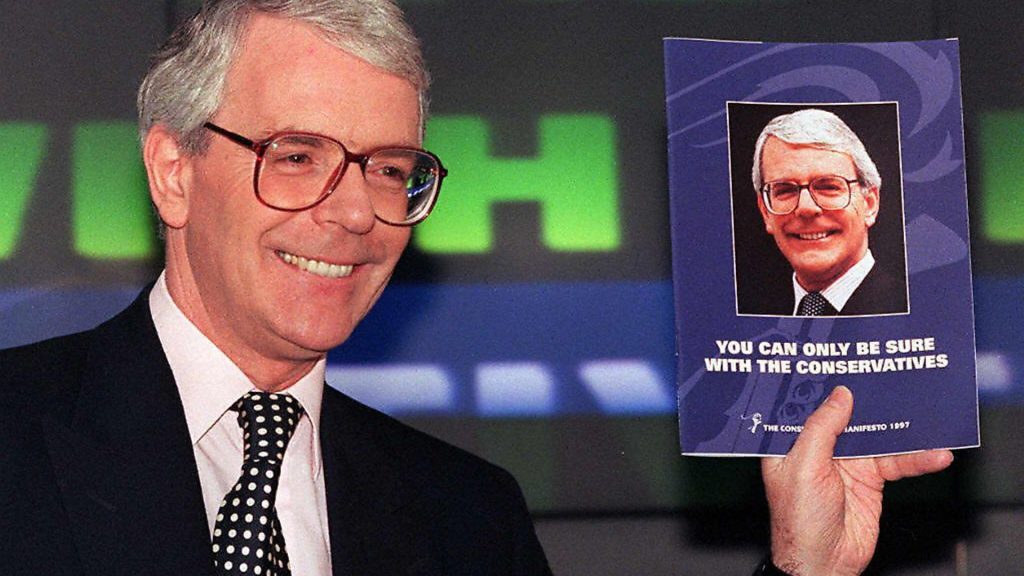

Interestingly, these are the same types of questions that were aimed at Blair’s predecessor, John Major, the epitome of the ‘sensible centrist’.

One word that came to epitomise the Major years was ‘grey’ – not only to characterise his rather lacklustre personality, but also his broader lack of a distinctive agenda or vision for the country. ‘Thatcherism with a grey face’, as some commentators had it.

What made life so difficult for Major was the circumstances he faced at the time; circumstances that are strikingly similar to those currently faced by Starmer.

A deeply divided party, a worsening economic recession and a series of political crises – including a major one over Europe – all hampered his ability to carve out a distinct and coherent vision for his party and government.

And, even though Major managed to confound his critics with an unexpected electoral victory in 1992, his overall lack of a definable agenda, combined with wider perceptions that he was dull and boring, made it ultimately impossible for him to compete with the much more charismatic Tony Blair.

It is still very early days for the new Labour leader. And the context that he has found himself in during the first four months of his leadership has hardly been conducive to forging a wider political project.

Yet, if he wants to emulate Blair’s success in making Labour an electoral force again, he might be advised to look further back in time to the Major years and recognise that being ‘sensible’ isn’t always enough of a platform for electoral success and political longevity.

Vision, charisma, branding, and perhaps even a slice of populism, have all become staple ingredients in an increasingly personalised and presidentialised political environment. And, in the UK context, we might attribute much of that environment to the legacy of Blair.

Peter Kerr is a senior lecturer in politics at the University of Birmingham; this article was first published by UK in a Changing Europe