A vanity not evident in his years on the fringe has become visible.

A retired MP whose left wing credentials are as good as those of his old friend, Jeremy Corbyn, sums up the Labour leader this way. ‘He’s a thoroughly decent human being who has led his life according to his principles. To say he’s a friend of terrorism is nonsense. He must be the most pacifist member of parliament, though he has sometimes been naïve. But I didn’t vote for him, I thought it would lead to electoral annihilation. I was proved wrong about that.’

The veteran might have added ‘so far’ because Labour is unlikely to face such an inept Conservative campaign next time. Does he agree with Corbyn when he predicts that Theresa May will be forced to call another general election within six months, one that Labour will win? Not really. The MP for Islington North since 1983 has spent most of his career ‘campaigning for faraway causes he couldn’t do much about. He took the right position on many causes 1,000 miles from home,’ the ex-MP observes.’ But the 2017 manifesto was different. It promised everything to everyone, saying someone else would pay for it. If we ever get near power this will come back to haunt us.’

Outside the much-diminished Campaign Group, many Labour politicians who served for decades at Westminster alongside serial rebel Corbyn (533 votes against the party line between 1997-2015 alone) are less gentle than that. Some who are happy to praise the leader’s personal qualities – ‘very likeable, he does not slag people off’, nor is he a cynic – do not extend much charity towards his close associates, hard-faced men (and office manager, Karie Murphy) with hard-left credentials throughout their careers.

Of John McDonnell, shadow chancellor and widely seen (together with my former Guardian colleague, Seamus Milne) as Corbyn’s political brain, the ex-MP mildly remarks: ‘McDonnell had a good campaign, he did well. But despite the affable veneer I sometimes wonder if he is drawing up lists of those to be shot.’ Ever the soft-spoken whisperer in the corner, Seamus sometimes managed to stimulate similar speculation at Guardian HQ.

Yet here is Uncle Jeremy in July 2017, 8% ahead of the dishevelled Tories in one poll, oozing new confidence in the Commons chamber where he is finally seen as a threat, rather than an opportunity. After all the abuse he has taken from colleagues as well as Conservative opponents who would not savour the triumph of watching Theresa May inviting him and other opposition MPs to ‘come forward with your own ideas’ on governing post-Brexit Britain – just weeks after she denounced him as a threat to civilisation?

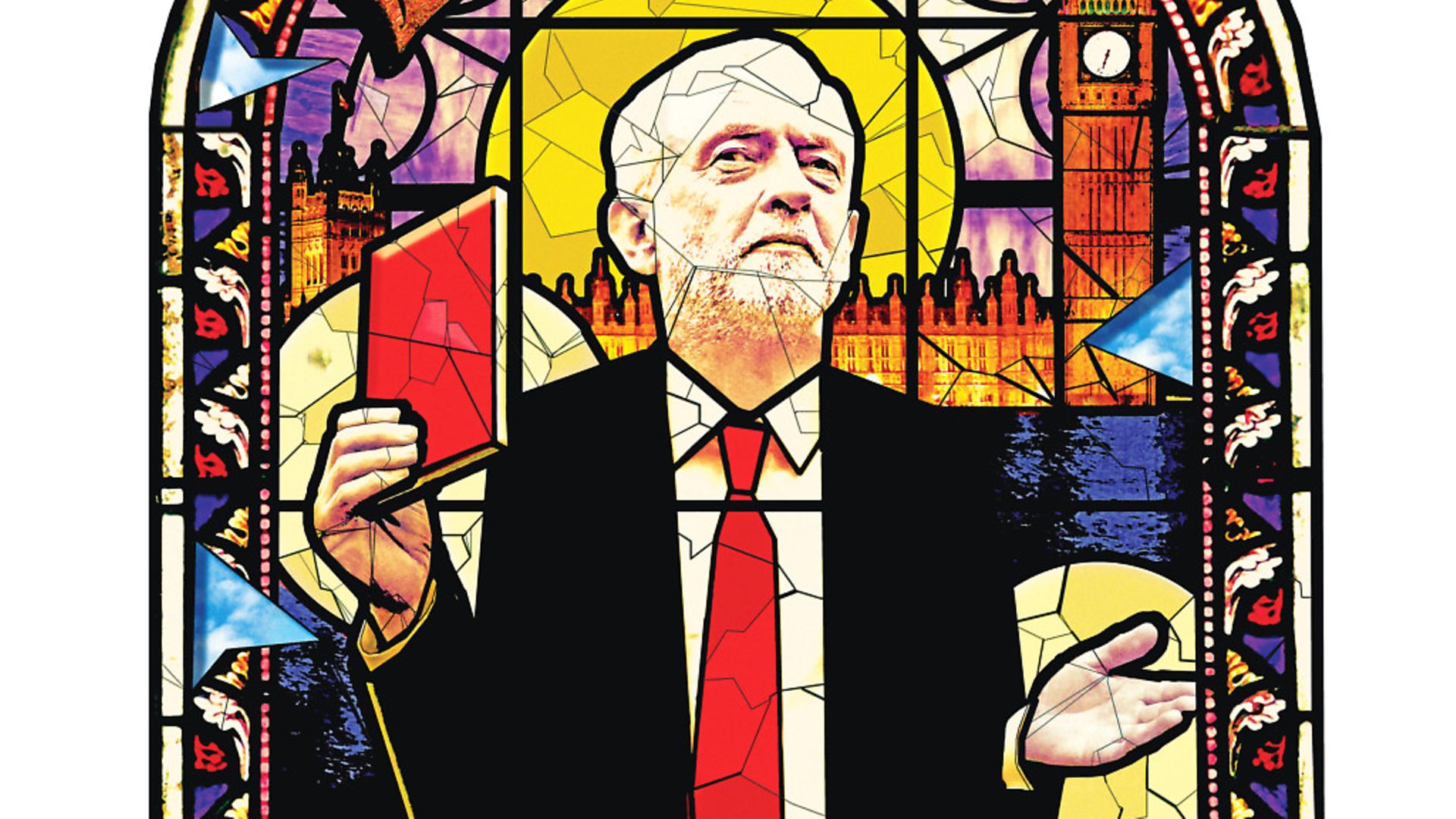

Corbyn is fresh from an election ‘victory’ tour of the Glastonbury Festival and chants of ‘Ohhh, Jeremy Corbyn’ from many thousands of mostly young, well-educated and usually well-scrubbed, middle class admirers. Critics who chuckled that the Corbyn coalition’s 40% share of the vote on June 8 was less working class than Tony Blair’s had a point: Kensington fell to Labour while Mansfield was lost. But the critics were then obliged to fume when he achieved comparable adulation at the Durham Miners’ Gala – the legendary ‘Big Meeting’ at the racecourse. In glorious sunshine many in the near record crowd of 200,000 chanted ‘Ohhh, Jeremy Corbyn’ too. Local wits promptly dubbed it ‘the working class Glastonbury’. On social media swarms of activists eagerly proclaimed that the Corbyn Nirvana is at hand while the party’s new chairman, ex-miner, Ian Lavery MP, who replaced Tom Watson, hinted at purges to come when he suggested it might be ‘too broad a church’ for its own good.

Corby-sceptics, among whom I remain enthusiastically numbered despite having voted Labour more times than Jeremy on June 8 (my own and two postal votes), must take a deep breath. They have to give the man some credit for surprising everyone – including himself – for firing up young voters in such numbers. They must ask themselves how this teetotal vegetarian managed it. Explanations range from the idealistic gullibility of heavily indebted students to the sheer incompetence of Theresa May’s Selfie campaign and strategy, not to mention the still toxic legacy of moderniser Blair’s Iraq war and the bankers’ crash wrongly blamed on Brown.

Other explanations are less negative. Chief among them is authenticity. In an age of cautiously scripted, sound bite politicians, too few able to convey passion or conviction for fearing of making a ‘gaffe’, Corbyn’s modest, uncharismatic sincerity on the leadership campaign trail in August 2015 – when I saw him address a vast crowd in Nottingham I realised he would win – was a tonic to young £3 activists newly bequeathed to politics by Ed Miliband’s reforms. But it also gave gnarled activists a glimpse of the old-time religion, all but forgotten in the transactional compromises forced on them during 13 years in power under Blair and Brown. Stephen Gilbert, author of an early biography, Jeremy Corbyn, Accidental Hero (Squint Books, £9.99), encapsulated his appeal with unintended eloquence.

‘Jeremy Corbyn had a great advantage when set against his rivals (Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall). Many of the questions of the day lend themselves to immediately comprehensible answers from his perspective. Austerity? Trident missiles? Against them. Public ownership of the utilities? Redistribution of wealth? For them. ‘End of’ as they say. These are not difficult decisions for him. They are logical, rational decisions drawn from his set of principles and values. People who glaze over when politicians weigh in on the benefits of PPI or the dangers of TTIP find Corbyn’s clears positions bracing, even when they don’t necessarily support them. We like this chap, they say. You know where you stand with him.’

In an age when Michael Gove has decried the usefulness of experts, in a week when crowds in the Strand are shouting down the medical expertise of doctors and the measured wisdom of judges on behalf of stricken baby, Charlie Gard, this is a perfect exposition of the populist case. It may not actually be right, but it feels right and that matters more. Donald Trump could not have better expressed the power of the emotional sugar rush, nor Marine le Pen, Nigel Farage or Italy’s pioneering populist, Silvio Berlusconi.

All the questions that Stephen Gilbert’s paragraph rhetorically pose are actually technically difficult to answer. So is Corbyn’s spectacular campaign suggestions that a Labour government might magic away – ‘deal with it’ – £100 billion worth of student debt, the product of a botched Coalition reform. Shadow education spokesman, Angela Rayner, admitted as much on Sunday sofa TV. ‘Jeremy’s said that’s an ambition, it’s something that he’d like to do. It’s something that we will not announce that we’re doing unless we can afford that. It’s a big abacus that I’m working on, it’s a huge amount, it’s £100 billion,’ she explained.

A Corbyn U-turn? Certainly not. The mood of the moment is ‘Down with detail, down with experts’. It is certainly ‘down with austerity’. If voters feel Corbyn is honest, as millions seem to do, they are not going to see it that way. It’s what Jeremy would like to happen, that’s enough for now. Despite the very visible failure of many of Donald Trump’s election promises – not to mention all his other problems – Trump commands the same uncritical adulation in the stricken heartlands of Middle America, as Margaret Thatcher once did in Middle England. Once the Iron Lady had acquired that reputation for steely intransigence she could flip-flop at ease. Who now remembers her surrender to the militant miners over 23 pit closures? Not even the miners do.

But that came after she’d won power and was exercising it, anxiously in private but publicly with a confidence not seen since Churchill in his prime. Thatcher’s 1979 manifesto was famously cautious (‘privatisation’ what’s that?), written by that notorious ‘wet’ Chris Patten, and designed not to hype expectations or give hostages to fortune, as Labour did on June 8. It is a widely shared belief among senior Labour politicians outside the Corbyn circle that the more expensive chunks of an otherwise reasonable 2017 manifesto were written in the confident knowledge that the party would lose. May’s serial errors almost derailed that strategic assumption.

Why was it done that way? As in the Blair-Brown years and during Ed Miliband’s five year tenure there is still scope for legitimate disagreement about how far ‘austerity is a political choice’ that can credibly be replaced by sensible levels of ‘borrowing to invest’ and boost recovery. As noted here last week, I remain conservative as to both scale and pace: there is much less room for manoeuvre than is casually claimed. Thus talk of renationalising the utilities, joyfully regarded as necessary by many activists, is a ‘distraction of time and money from other priorities’ to others. They have learned the hard way that better regulation is the way ahead for rail and power.

The key to the manifesto’s casual largesse lies in Corbyn’s – the champion of faraway causes – indifference to credible economic detail and to the greater priority his team gave to retaining ‘power within the Labour party rather than power for the Labour party’. It is not that more serious politicians like McDonnell have not been tempted in recent months by the prospect, however remote, of becoming chancellor. Until a moment of gesture politics – proposing to set an illegal budget – forced Ken Livingstone to sack him, McDonnell was regarded as a capable chair of finance at the old GLC in the 80s.

But as Camp Corbyn’s Mr Angry, his career punctuated by well-documented verbal outbursts, McDonnell must know he can never hope to succeed his cuddlier comrade as party leader. Some gossip suggests he hopes to insert a northern and left wing working class woman into the post. That currently translates as Angela Rayner or her flatmate, Rebecca Long-Bailey, though that sort of sweepstake can quickly change in the politics of a leader’s court where the wrong word out of place can mean banishment.

Some confidently assert that if May’s plan – a Commons majority of 50 to 100 – had actually worked Corbyn would have been eased out next year, as might have been the case if May had tried to stagger on until 2020. Now there is no moving him (‘completely secure’ says Tom Watson) as long as he wants to stay. ‘He had the perfect result, more Labour MPs, in part thanks to him, and no responsibility for delivering on the promises and pledges he made,’ says one veteran of many elections who insists that Corbyn would have been persuaded to hang on whatever the result. A vanity not evident in his years on the fringe has become visible. It is an understandable human weakness and at 68 he is younger than Trump (71), let alone Vince Cable (74).

In any case, as with the sagging Tories, there is no obvious replacement candidate on either wing of the party, the talent pool is as depleted as a Kentish reservoir in August. Rule changes to be agreed at Labour’s 2018 conference will make it easier for the left to nominate their own candidate without help from the right that will not be forthcoming again (a 5 or 10% nomination threshold from MPs, not the current 15%). Bennite mandatory reselection purges for ‘disloyal’ colleagues like Luciana Berger or Chris Leslie, already singled out for hairdryer treatment? Surely the current mechanism of trigger ballots should suffice. Purges will not fill the shallow talent pool and the right wing press is already building a ‘hard-left bullying’ narrative over abuse of Conservative MPs. It is a theme which averts its gaze from Viscount St David’s conviction for incitement to violence against Remain campaigner, Gina Miller, and actively incites ‘Crush the Saboteurs’ campaigns against Tory Remain MPs. Ian Lavery took pre-emptive steps on Tuesday by accusing Conservative HQ of orchestrating the media campaign.

In such angry populist times – ‘Days of Rage’ not confined to either side – nor will greater activist power on the National Executive (NEC) or even in nominating leadership candidates, do much good. Few people may remember the Bennite heyday when Labour MPs were corralled in a section of the party conference hall and treated like war criminals by many of those present. But three further election defeats were to follow. Most voters still see MPs as representatives, not as delegates of Unite or of the Daily Mail.

Tom Watson hinted as much in a tightrope walk of an Observer interview two Sundays ago. Even to entertain disruptive rule changes underlines how many activists believe that ‘one last heave’ – the oldest piety in elective politics – will surely topple the Tories next time. Up on his Observer tightrope Watson deployed the tactful language of euphemism to indicate otherwise. Wouldn’t it be wonderful, he said, if Corbyn managed to retain the enthusiastic support of young voters while ‘giving greater reassurance to our traditional working class voters, some of whom left us on issues like policing and security’.

That is putting it gently. The reality is that there were two Labour election campaigns this summer. One was built around the strange but potent cult of Corbyn (did any crowd at Lords ever chant ‘Ohhh, Clement Attlee’?) and the online ground war brilliantly fought by Momentum activists with guidance from their counterparts in Bernie Sanders insurgency against Hillary Clinton’s over-developed sense of entitlement. With their emotive films and simple slogans, they whacked the smug Tory machine.

The other campaign was fought more conventionally on the doorstep where sitting Labour MPs and candidates who picked up negative feedback over Corbyn, both as a leader of doubtful mettle and as a well-meaning peacenik, told wavering voters ‘don’t worry, he’s not going to win. You’re voting for me’. I sat next to one over a meal on Saturday night and cast my three votes in the same spirit for my hard-working local anti-Corbyn MP, whom I will not identify on safety grounds (he won and is still at large). That customised approach to voters, beloved of Lib Dem pavement politicians long before data mining was dreamed of, will be harder to repeat now that Corbyn has got a 40% vote share and is a ‘mere’ 64 seats short of a Commons majority.

The vagaries of Brexit and the divisions in the Tory party over Brexit make the future even harder to predict than the immediate past. The rising tide of political resentment across many advanced western democracies, ones with very differing problems, has latched on to the frail, improbable figure of Corbyn. During the Brexit referendum a year ago it found hope in Nigel Farage and Boris (‘most trusted’) Johnson, an even more implausible – and much more unsavoury – pair. In a single decade America has veered between George ‘Dubya’ Bush, the austere and cerebral Barack Obama and the mendacious, narcissistic populism of Donald Trump. France has hopped from hyper-active Sarkozy to messianic Macron via the lethargic Hollande, Italy from Berlusconi to Renzi and halfway back via the Five Star Movement. Germany may be solid as long as Merkel soldiers on. But we live in highly volatile times.

Is Corbyn serious about the opportunity which circumstances seem to be offering? Britain faces deep structural problems, an ageing society as well as one heading to the EU’s Exit door as economic warning lights flash with ever-increasing frequency. Political and social cohesion is under strain, as is inter-generational solidarity, too many debt-burdened students, neglected old and feral children. The extent to which Faraway Jez is willing to buckle down on such challenges beyond easy clichés is not clear. In contrast to the Blairite Matthew Taylor’s solid report on the gig economy this week, the signs are not encouraging, the Labour leader remains in campaigning model. It’s what he does best, except during Brexit referendums.

There is a telling incident in his CV which one old hand recalled this week. It came when Corbyn and his Chilean second wife, Claudia Bracchitta, publicly fell out over the education of their eldest son in 1999. To the credit of both, the couple – who had separated but were still sharing a house – gave a sympathetic interview with the Observer’s Andy McSmith, explaining their situation after a welter of hostile press attacks. Claudia wanted their boy to go to a grammar school outside the then-failing Labour borough’s schools. Jeremy wouldn’t compromise his principles.

They later divorced. As the Observer noted at the time, Corbyn was well-meaning, soft-spoken and uncynical, a marginal figure with no hope of becoming a minister (‘his prospects are limited, at best’) who was – irony alert – under threat of deselection by moderates. The striking thing, McSmith reported, was that, a few days short of 50, Corbyn still believed what he believed in his 20s. He wasn’t a sell-out. But he also agreed to let Claudia take the decisions on their three sons’ education.

So the boy (not the son who is now McDonnell’s chief of staff) went to grammar school while Jeremy, holder of the Gandhi International Peace Award, stayed pure. But, as someone said of Gandhi, it always took a lot of hard work by other people to keep him holy.