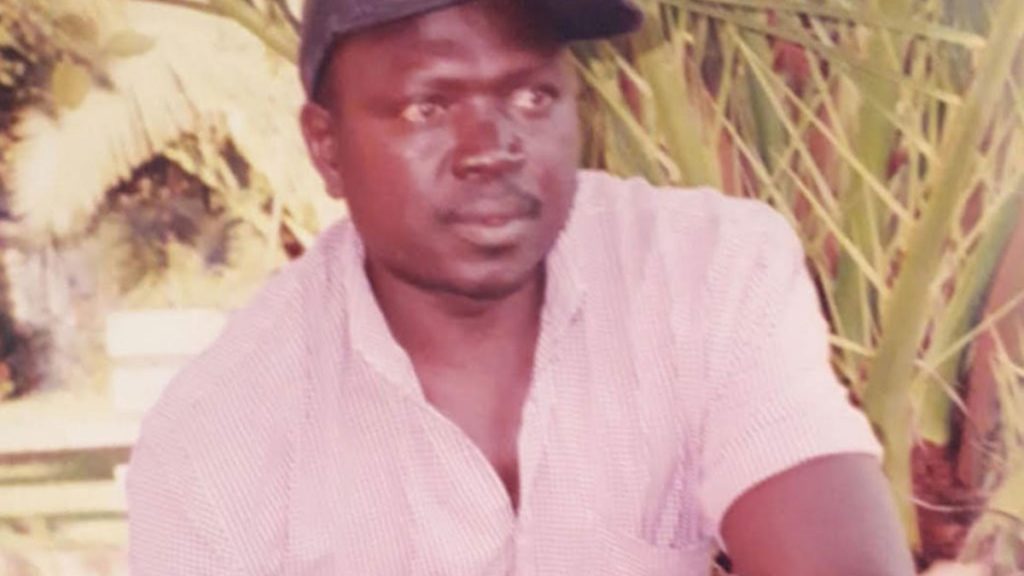

The death of Emanuel Gomes during the recent lockdown reveals much about how we live, who we value and how we are governed. JACK SHENKER tells his story.

For Emanuel Gomes, the most striking thing about the coronavirus lockdown was that it never existed. ‘From this evening, I must give the British people a very simple instruction: you must stay at home,’ Boris Johnson told the nation on the evening of March 23, as he declared a national emergency and announced an ‘unprecedented’ support package for workers whose lives would now be disrupted. But Emanuel’s life wasn’t disrupted at all.

He continued to board the tube each day from his sublet in Plaistow, east London, to an empty office block in the city centre, where he spent the night shift sweeping untouched carpets and scrubbing unused toilets.

He continued to collect his wages, which at £9.08 per hour were just above the legal minimum, and he continued to send most of it back to his family in Portugal and the west African state of Guinea-Bissau. And when he began to feel strange – just aches and pains at first, then congestion, confusion, and finally a full-blown fever – he continued coming into work, because he couldn’t afford not to.

Emanuel and his colleagues had petitioned their employer for occupational sick pay, pointing out that failing to guarantee workers a basic survival income if they fell ill would force potentially infectious people to leave home and endanger others, but were refused. Their complaints about a lack of PPE provision and the absence of effective social distancing measures in the workplace were also rejected.

‘The cleaners believe they are putting themselves and others in serious, imminent and unavoidable danger,’ managers were warned in an email sent at midday on April 23. No action was taken.

The previous evening, as Emanuel arrived for his shift, he had felt worse than ever; so unwell, in fact, that he could barely stand. ‘I took him home on public transport,’ recalls Bio Fara, a fellow night shift cleaner. ‘When we got to Victoria station, he didn’t even know where he was.’

Emanuel was pronounced dead by paramedics at 10.30pm, one month exactly after the prime minister first ordered people to stay at home for their own protection.

He was 43 years old. ‘I don’t know how to explain these things, I don’t understand,’ says Fatima Djalo, another cleaner on the same site. ‘He was a human being: they could have done something, and they didn’t.’

Many of Emanuel’s colleagues are now questioning why the people that he worked for were so casual about the risks he faced during the pandemic, about the material insecurity that exacerbated them, about his bosses’ apparent disregard of the British government’s blueprint for saving lives. The answers should matter to all of us, because Emanuel Gomes worked for the British government.

The Ministry of Justice headquarters at 102 Petty France lies between St James’s Park to the north and Victoria to the south, and towers over its surroundings. From these 14 floors of brutalist concrete and glass, the country’s courts, prisons and probation services are administered. ‘We work to protect and advance the principles of justice,’ runs the ministry’s mission statement. ‘Our vision is to deliver a world-class justice system that works for everyone in society.’

The issue of who gets seen and valued as part of that society – whose lives are deemed to matter – has acquired new resonance in the age of coronavirus.

This pandemic landed in a country beset with economic inequalities and social divides, and those fault-lines became a pathway to deadly infection.

According to ONS data, death rates among men in elementary work such as cleaning are double the national male average and almost four times higher than for men in professional occupations.

Black males are four times more likely to die from Covid-19 than their white counterparts. A lockdown that has often been described as a universal phenomenon was, in reality, a very different experience for large sections of the workforce who were not granted the luxury of sheltering at home; those who continued to travel into their jobs were disproportionately poor and non-white.

The virus itself may not discriminate between humans, but the nation it has wreaked havoc on most certainly does.

The story of how Britain’s government handled a coronavirus outbreak within its own walls tells us much about what that discrimination looks like during a national emergency.

Ministers ordered individuals and employers to take exceptional steps to prevent the spread of Covid-19, and publicly venerated key workers whose labour was necessary to keep the country functioning.

Behind closed doors, at the Ministry of Justice at least, its behaviour stood in stark contrast to its rhetoric. ‘Cleaners are people,’ says Luis Eduardo Veintimilla, another Ministry of Justice cleaner.

‘We are humans and we have to respect human lives. That means taking precautions to protect people. But at the ministry, this didn’t happen. No one took any responsibility, and now they are culpable for what happened.’

What happened at the Ministry of Justice was that after being designated as key workers during lockdown and instructed to attend work as normal, cleaners like Luis and Emanuel got sick.

Circulating in small teams through a near-deserted building – most of the civil servants having switched to working from home – they fell ill, one after another, with no support network to help them when they needed help the most.

Their supervisors and managers had either disappeared or were unresponsive; their fears for their safety were overlooked. Nobody told them what to do if they developed a suspected case of coronavirus. Those compelled to work by financial hardship felt terrified, while those that took it upon themselves to follow official guidelines and self-isolate at home were stripped of their pay, or dismissed.

‘There is no evidence to suggest there is or ever has been a coronavirus outbreak at Petty France,’ the Ministry of Justice has insisted. Our investigation has shown this to be incorrect: at the height of the pandemic, at least seven ancillary workers at 102 Petty France developed symptoms associated with Covid-19, two of whom died.

Testimony from multiple cleaners, alongside emails and phone messages, reveals that not only was OCS – an outsourcing company that contracts cleaners on the Ministry of Justice’s behalf – aware that an outbreak was spreading on the site, but that it ignored increasingly desperate pleas from workers asking for protective equipment, clearer guidance, and the right to stay home without penalty if they became infected.

‘It was us that had to go into the Ministry of Justice each day searching for the virus, to clean it and to chase it away,’ says Fatima Djalo. ‘They seem to think our lives are worthless. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because we are foreigners. Maybe it’s because they believe we are drones.’

It was Pedro who came down first. Thin, careful and softly-spoken, Pedro is a stalwart of the Ministry of Justice cleaning team – a diligent, polyglot community of Spanish, South American and West African migrants who between them cover more than 50,000 square metres of prime governmental real estate, 24 hours a day.

On March 17, a week before lockdown, Pedro began to feel some pain at work. That in itself wasn’t unusual – he has undergone operations before to correct a problem in his legs that he believes is caused by the hard, physical labour his job entails – but this was different: odd strains and spasms that danced all over his body, and a rising temperature that seemed like it would never stop.

The following day, Pedro stayed at home and called in to say that he was ill, even though OCS does not provide its cleaners with any sick pay beyond the statutory minimum of £95.85 a week, a policy that has remained in place throughout the pandemic.

‘I was very worried, because I need my wages to pay my rent, to buy food,’ he told me. ‘What can you do with no money?’ But by this stage, Pedro had lost his sense of taste and smell and was having difficulty breathing. The NHS 111 service diagnosed him with suspected coronavirus and instructed him to self-isolate along with his wife, who had developed the same symptoms as well.

Back at the ministry, Luis Eduardo – who arrived in London via Ecuador and Barcelona eight years ago and fell in love with a land that felt ‘like a whole new world’ – was growing anxious. ‘We were hearing about coronavirus on the news; at first people said it was like a cold, but then we realised it was more serious,’ he explained. ‘By then, Pedro was already sick with all the symptoms, and he had been in contact with all of us.’

Luis Eduardo sought a meeting with the senior OCS supervisor at the Ministry of Justice, but he was away, and the office where the cleaners’ manager usually sat was empty. He eventually tracked her down and asked if there was going to be a staff meeting to provide information on Covid-19 and how cleaners should protect themselves in the workplace. ‘She said ‘no, nothing’,’ claims Luis Eduardo. ‘She said everything was going to be OK.’

The following Monday, a national lockdown was declared by the prime minister, leaving the cleaners unsure about whether they were supposed to continue turning up for their shifts. ‘It was scary and depressing,’ remembers Fatima of those early, eerie days when the ‘computer people’ – as she calls the ministry’s office workers – had nearly all disappeared, and the security guards were the only other faces to be seen on site.

Benito Medina, a 40-year-old cleaner from the Canary Islands, told me that he panicked on his first encounter with mile upon mile of deserted corridors. ‘You have this fear that something bad is going to happen to you,’ he said.

Later that week, both the Ministry of Justice and OCS issued letters to the cleaners informing them that their role was ‘essential in the running of the justice system’, and that they had been formally designated as key workers to whom lockdown restrictions did not apply. By that point, Luis too had fallen sick.

On March 24, the first full day of lockdown, Luis Eduardo remained at home and emailed his managers to explain why. ‘I have tried to reach you at the office but every time I’ve looked for you, you haven’t been in,’ he wrote, raising his concern that the cleaners had not been kept informed about Pedro’s condition.

‘I am not feeling well. I have a headache and upset stomach. It is at this time we need clear concise leadership from management. Nothing has been communicated to me on what steps to take, except that which is on the news. Why haven’t we been provided with masks?’

In a reply, his manager refused to discuss Pedro’s case and declared ‘OCS are taking [the] lead from our client the MOJ [Ministry of Justice] who have stated all buildings are to remain open and are business as usual. We have not had communication to close or send anyone home.’ She reprimanded Luis Eduardo for not following the correct sickness reporting procedures, and warned him that unless this was rectified, he would be categorised as absent without leave.

We now know that, as well as Luis Eduardo and Pedro, a third outsourced worker at the Ministry of Justice site – not a cleaner this time, but an engineer contracted by the property services giant Kier – also stayed at home that day with coronavirus symptoms; he would never return to work, and passed away a month later.

Among the remaining cleaners, starved of any guidance from above and reliant on WhatsApp messages between each other for scraps of information, an atmosphere of dread began to spread. ‘They told us nothing,’ says Florencio Hurtado, a night shift worker who, like most of his colleagues, juggles several outsourced cleaning jobs to make ends meet, often clocking up more than 80 working hours a week. ‘At no moment did anybody say anything to us about being allowed to stay at home, and for most of us there was no way to stay at home anyway, because if we don’t work, we don’t get paid. And this is London: life is difficult, and very expensive, so people carried on coming in even though they were feeling sick. I was one of them. We had no choice.’ Before the week was out, Florencio and others on the night shift came together to demand answers; the senior supervisor was absent but spoke to them over the phone instead. ‘We said we needed protective materials, but were told, ‘Why? There’s no cases, there’s no point in giving you guys anything’,’ Florencio recalls. ‘We couldn’t get answers about our rights,’ agrees Luis. ‘The problem was that the management we are dealing with is interchangeable – it is the Ministry of Justice, and it is OCS, and if you have a problem one of them says ‘oh it’s their fault’ and the other one says ‘no it’s their fault’, and you are left in the middle.’

It was around this time that the CEO of OCS, Bob Taylor, released a public statement on coronavirus. ‘In these uncertain times, remaining true to our values has never been more important,’ he noted. ‘We’re in this together.’

Public-sector outsourcing, in its modern guise, stretches back to the 1980s when Margaret Thatcher’s administration began introducing compulsory competitive tendering across a wide swathe of government activity. In subsequent decades, cross-party consensus solidified around the efficiency and desirability of market mechanisms, and by 2017 Whitehall was spending £284 billion per year on buying goods and services from outside suppliers – entangling private companies with the provision of a vast array of public services, from cooking school dinners to constructing hospitals. The Ministry of Justice is the largest central government outsourcer of all, one of only four departments that spends more than half of its entire budget externally. It has also been the focal point for a series of high-profile outsourcing failures, from controversies over offender tagging services and crisis-hit prisons, both run by G4S, to the spectacular collapse of outsourced probation services, all of which have now been brought back in-house.

‘The dynamic is very often set up to drive everyone obsessively towards the lowest cost – at the expense of almost everything else, including quality of service and treatment of staff,’ argues Tom Sasse, a senior researcher at the Institute for Government and co-author of two recent reports on government outsourcing. ‘Private providers are incentivised to bid very low, and it’s rare for a contract to be awarded to a bid that doesn’t offer the lowest price.’ The use of an outsourcing firm also enables government departments to apply an extra layer of management between itself and many of the workers it relies upon to function, who under the terms of the outsourcing contract become formal employees of the private provider. ‘What it means is that you create a two-tier workforce,’ claims Molly de Dios Fisher, an organiser with the United Voices of the World (UVW) trade union which represents a large number of cleaners at the Ministry of Justice. ‘The client, i.e. the actual place where someone is working, has little legal responsibility or obligation to them, and because of the nature of the outsourcing contract the worker themselves ends up with lower pay, lower terms and conditions, and a job which is much more precarious compared to directly-employed staff.’

Cleaning, of course, is a function that many businesses outsource, although several public-sector organisations – from the Imperial College NHS Trust to Kensington and Chelsea council – have recently moved to bring their cleaners back in-house. The current contract between the Ministry of Justice and OCS – a facilities management company privately-owned by the Goodliffe Family, who are worth £191 million and appear on the Sunday Times rich list – comprises a five-year deal, signed in 2018: taxpayers send the firm £17.5m per annum, and in return OCS provides the ministry with security, catering, cleaning and other services.

Around 20 cleaners are on regular shifts at the ministry, but details of the contract that determines the nature of their employment are not made public; Freedom of Information requests which touch upon it are routinely rejected on the grounds that disclosure could prejudice commercial interests. Also shielded from view are the third-party subcontractors used by outsourcers like OCS to provide various elements of their service, including temporary staff who are often brought in to do the same work as their OCS-employed colleagues, but whose status is even less secure.

One such worker at the Ministry of Justice was Rodrigo Rendifo, a former Colombian truck driver, who had been part of the night-shift cleaning team ever since he was recruited by an OCS supervisor in September 2019. By early April, security guards were telling cleaners, including Rodrigo, that up to a dozen cases of suspected coronavirus had been identified among those who were still working in the Ministry of Justice headquarters, with three specific areas of the building named as being potential sites of infection. Another staff meeting with junior supervisors in early April, in which the cleaners pressed for more clarity and to be given masks, ended in frustration. ‘I kept asking my colleagues, ‘What’s the deal here? Where are the managers?’,’ Rodrigo told me. ‘They said, ‘They’ve left us in the lurch, and we’re here carrying on with the cleaning.’

Rodrigo was by now beginning to feel sick himself: he developed a new cough, muscle aches, and then a fever. He tried to keep working and spent several days on site while displaying symptoms. When he finally managed to track down a supervisor and explain the situation, he claims he was initially told to continue coming in; only on April 13, having spoken to the senior supervisor and been reassured that he would continue receiving his wages if he self-isolated, did Rodrigo return home. After seeking medical attention he was diagnosed with suspected coronavirus and provided with doctors’ certificates confirming that he was unable to work for the next three weeks. On April 29, before that period had expired and while he was still recovering from his illness, he received a text message from a company called PRS, a recruitment agency used by OCS to provide labour for their Ministry of Justice contract. Rodrigo knew very little about PRS; he had never, to his knowledge, signed any paperwork with them, entered into any communication with them, or had dealings with any company other than OCS. In fact, it turned out, he had actually been a PRS employee all along – at least until now.

‘Hi Rodrigo,’ the message read, ‘Your contract at OCS has come to an end, please DO NOT return to site. Many thanks, PRS.’ Perplexed, he phoned the senior OCS supervisor but he professed ignorance. When he tried to ring again, Rodrigo couldn’t get through; he believes that his number had been blocked. In common with all the other cleaners who self-isolated, Rodrigo’s wages for this period were never paid.

In the week before Rodrigo was fired, UVW wrote a formal letter to Peter Tierney, the OCS account director for the Ministry of Justice contract, setting out serious concerns over the treatment of workers during the pandemic and accusing OCS of taking ‘no meaningful action to protect the health of the cleaners, despite the fact that a breach of [health and safety regulations] may amount to a criminal act.’ Robert Buckland QC, the secretary of state for justice, was also a recipient of the complaint, which went on to point out that Covid-19 was ‘potentially deadly’.

Luis Eduardo too – still at home with the virus, and appalled to discover that nearly all of his wages, apart from statutory sick pay, had been docked – was urgently contacting managers, and trying to impress upon them the gravity of the situation. ‘If it wasn’t for a lack of procedures, communication, and [the] general welfare of your employees, I wouldn’t have been sick,’ he wrote, in an email, before going on to warn that the lack of a ‘proactive response to this pandemic’ could end up killing colleagues. ‘People with underlying health conditions after coming into contact with Covid-19 are more susceptible to dying! So we must not downplay what is going on… I am very, very concerned.’

OCS acknowledged receipt of UVW’s letter at 2pm on April 23, although they did not provide a response until several days later, arguing that the company was operating in full compliance with Public Health England guidelines and had been working extremely hard to protect the wellbeing of its staff. It made no difference. Later that evening, Emanuel Gomes died.

Emanuel was one of five children, and the only son in a family where the father died young; Emanuel’s wife, Neneta, told me that ‘from the day he was born, he had to be a man’. His journey from Guinea-Bissau to the UK went via Senegal, the Ivory Coast and Portugal, leaving behind a complex web of cousins, colleagues and friends. By the time he arrived in London, however, Emanuel was alone. Neneta lived in Lisbon and Emanuel dreamed of bringing her over to join him, but the problem was always money – on such low wages, he could barely afford his own accommodation, never mind anybody else’s. And besides, the work was relentless. ‘They would give him some hours, then reduce the hours, then change the shift pattern, and so on, and it made things like getting a rental contract really difficult,’ said Neneta of Emanuel’s schedule at the Ministry of Justice. ‘He worked so hard.’

But Emanuel knew however bad things were, it was preferable to unemployment. His plan was to send enough money back to his family for them to one day build a house in his home village of Bara, and for everyone to be reunited. Earlier this year, he booked an airline ticket to Guinea-Bissau; he intended to travel there in June, and scout out some land.

He dared not take too much leave though, even if it were authorised. ‘He was always fearful of losing his job,’ remembers Dominique Gomis, a close relative of Neneta’s who works as a bus driver in Paris, and whose English-language skills were regularly called upon by Emanuel once he was in London. ‘When he began to feel ill, we told him to stay home, but he had to go back to work,’ said Neneta. ‘His fear was that if he stayed at home, he wouldn’t be paid and he would be laid off.’

It was Emanuel’s housemate, who does not wish to be named, that first noticed something was wrong. It seemed like a strange kind of tiredness, so intense at times that Emanuel struggled to even put his shoes on. ‘It’s just aching in my muscles, it’s nothing,’ Emanuel insisted. To his wife Emanuel described himself as having a bad flu.

‘I was saying to him, ‘We are in quarantine here in Portugal, why are you still going to work in London, what protections are there?’,’ Neneta recalls. But Emanuel, more accustomed to being a care-giver than a receiver, continued regardless. ‘He was always trying to help everybody he knows, in one way or another,’ Neneta told me. ‘He was funny; he would ring me up to make jokes, and if he ever noticed that I wasn’t smiling he would find a way to make me happy.’

By the evening of April 22, when Emanuel arrived for the Ministry of Justice night shift, he had a high temperature and was visibly dizzy and disorientated. Bio, a fellow cleaner from Guinea-Bissau, took him aside and asked him what was wrong; Emanuel didn’t know, but told Bio he hadn’t eaten for a week. Bio suggested calling an ambulance but Emanuel protested – he wanted to work his shift – yet eventually, he allowed himself to be taken back home by his colleague.The following day, alone in his room, Emanuel’s condition worsened. He managed to ring Neneta at about 8pm, saying that his flu seemed to have grown more severe; he promised that he would seek medical attention, and then phone her back later that evening. At midnight, Neneta received a call from Emanuel’s housemate. Paramedics had arrived too late, he told her, gently. Her husband was gone.

In death, as in life, Emanuel’s existence in Britain seemed to slip through the cracks. From afar, his family spent several days attempting to track down his body, which had become lost in a maze of pandemic bureaucracy; a distant relative who is based in Essex eventually located it in one of the emergency morgues for Covid-19 patients that had been established in the capital. Emanuel’s belongings, including the identification documents needed by his family to close his bank account and process other bits of post-death administration, had been removed by police officers who attended the death; it took multiple phone calls, emails and visits by Neneta to different east London stations before she was able to track them down to a police base in Barking – in the dog kennels, where a special quarantined area for Covid-19 related items had been set up.

Perhaps most frustratingly, despite both the London Ambulance Service and Metropolitan Police officially categorising Emanuel’s passing as ‘death due to Covid-19’, his family were made to wait eight weeks before receiving a formal notice from the coroner. When it came, it contained a shock; the post-mortem report lists ‘hypertensive heart disease’ as the official cause of death, rather than coronavirus, and incorrectly states that he had not been suffering from flu-like symptoms before dying.

The report notes the findings of the medics who were on the scene at the time, but offers no explanation as to why Covid-19 is not listed as a cause of death; there is no evidence that Emanuel was ever tested for the infection, either before or after he died. Medical experts we consulted, who were able to study the post-mortem report with the family’s permission, expressed surprise at its conclusions, pointing out that Emanuel’s demographic profile and history of diabetes would put him in a high-risk category for coronavirus, and that hypertension – or high blood pressure – is a common condition in much of the population, and doesn’t in itself explain why somebody might die.

‘What we know from the report is that the lungs were congested and oedematous, which means basically they were full of fluid, and I think it’s likely that this gentleman died in the end because of that,’ commented Ajay Shah, the British Heart Foundation professor of cardiology at King’s College London, and director of the BHF Centre of Excellence.

‘People with Covid-19 present in a lot of different ways, but there is usually, almost always, something wrong with the lungs.’ Professor Shah told us that there was insufficient information in the post-mortem to say definitively whether Emanuel had coronavirus or not – but that the information present was certainly consistent with a coronavirus fatality.

‘If you’re asking me, could this be Covid-19, then I can’t say for sure,’ he said, ‘but it absolutely could have been.’ He added that it was a matter of public record that excess deaths in the pandemic period far outstrip the number of fatalities directly attributed to coronavirus, and that all aspects of the medical system were under immense pressure during those early weeks, meaning that many deaths from Covid-19 or other causes will have been miscategorised. ‘It’s hard to criticise the person who did the post-mortem,’ he remarked. Emanuel’s family are now considering requesting a second, independent post-mortem; the East London Coroner’s Court said they could not comment on the case.

On the same day that Emanuel died, the outsourced engineer – who was also working at the Ministry of Justice site and had fallen sick the same time as Luis – passed away too. In a statement, his employer Kier confirmed that this was a suspected case of Covid-19, and that the Ministry of Justice had been closely informed of the situation throughout. News of the two deaths swiftly began to circulate among cleaning staff, but at a meeting called by supervisors – which the cleaners claim was the first time OCS management had volunteered any meaningful information to them regarding the pandemic’s impact on workers at the site – they were told that the fatalities were not caused by coronavirus. At this stage, the Ministry of Justice already knew that the engineer had died of suspected Covid-19, and the only information available on Emanuel’s death was that it had been categorised by paramedics as being due to coronavirus.

‘I was so worried that I went to [the senior supervisor], and said ‘That doesn’t make sense, we know it was coronavirus, even I had coronavirus’,’ remembers Pedro, the first cleaner who fell sick, who was by now recovered and back at work. ‘He told me I hadn’t had the virus at all. He said I’d just had the ordinary flu.’

In a speech earlier this month laying out his vision for the country beyond Covid-19, Boris Johnson hailed a nationwide ‘display of solidarity not seen since World War Two’ and declared that the UK would ‘bounce forward – stronger and better and more united than ever before.’ Who may benefit from that bounce forward, and who may be sacrificed for it, remain to be seen.

As lockdown eases, and more people return to work, the question of power dynamics between companies and their staff is set to intensify. The government has claimed that ‘good British common sense’ will enable employers and employees to find a way around any disagreements over acceptable risk levels in relation to coronavirus; the experience of those who clean its own ministries suggests that reality is far more complex.

OCS, meanwhile, has begun advertising itself as a market leader when it comes to protecting workforces in a post-pandemic world. ‘Companies that care about raising standards in the industry value their cleaning operatives, their knowledge and their experience,’ noted the firm in a recent publication. ‘They recognise and reward their colleagues [and] look after both their physical and mental health.’ In a recent letter to its cleaning operatives at the Ministry of Justice, OCS informed them that they would soon be receiving a pay rise of just under 14 pence an hour.

In a statement, the Ministry of Justice claimed there was no evidence of a coronavirus outbreak at its headquarters, and insisted that it kept in regular contact with its contractors to make sure employees have the appropriate protection. ‘We are grateful to all our contracted staff for working throughout the pandemic to make sure our buildings are safe for those who need to use them,’ said a spokesperson. OCS declined to comment, as did the PRS recruitment agency who terminated Rodrigo’s employment at the ministry.

For Luis Eduardo, the behaviour of the Ministry of Justice and its outsourcing partners toward its cleaners during a national emergency was no anomaly; it was the inevitable consequence of a system designed to keep people like him insecure, and disposable. ‘We are not valued,’ he told me. ‘We are seen as lower than the rubbish itself.’

When Luis Eduardo came down with coronavirus, he said it felt like someone was cutting him from within, as if he had wounds on the inside of his body. ‘I couldn’t speak, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep,’ he remembers, quietly. ‘I thought I was going to die.’

Like Emanuel, an ambulance was called for him but on this occasion the paramedics arrived in time; they discovered that his oxygen levels were low, and were eventually able to stabilise him. Of his lost colleague he said: ‘Emanuel was scared to stop working, and the company just washed their hands of it. They never, ever addressed what someone should do if they thought they had the virus. But we are not the dirt we clean.’

Some names have been changed to protect the identities of the cleaners involved.