Giuseppe Sollazzo on one of the contest’s memorable winners – a love song to the single market

Could a song about the European Union win the Eurovision contest?

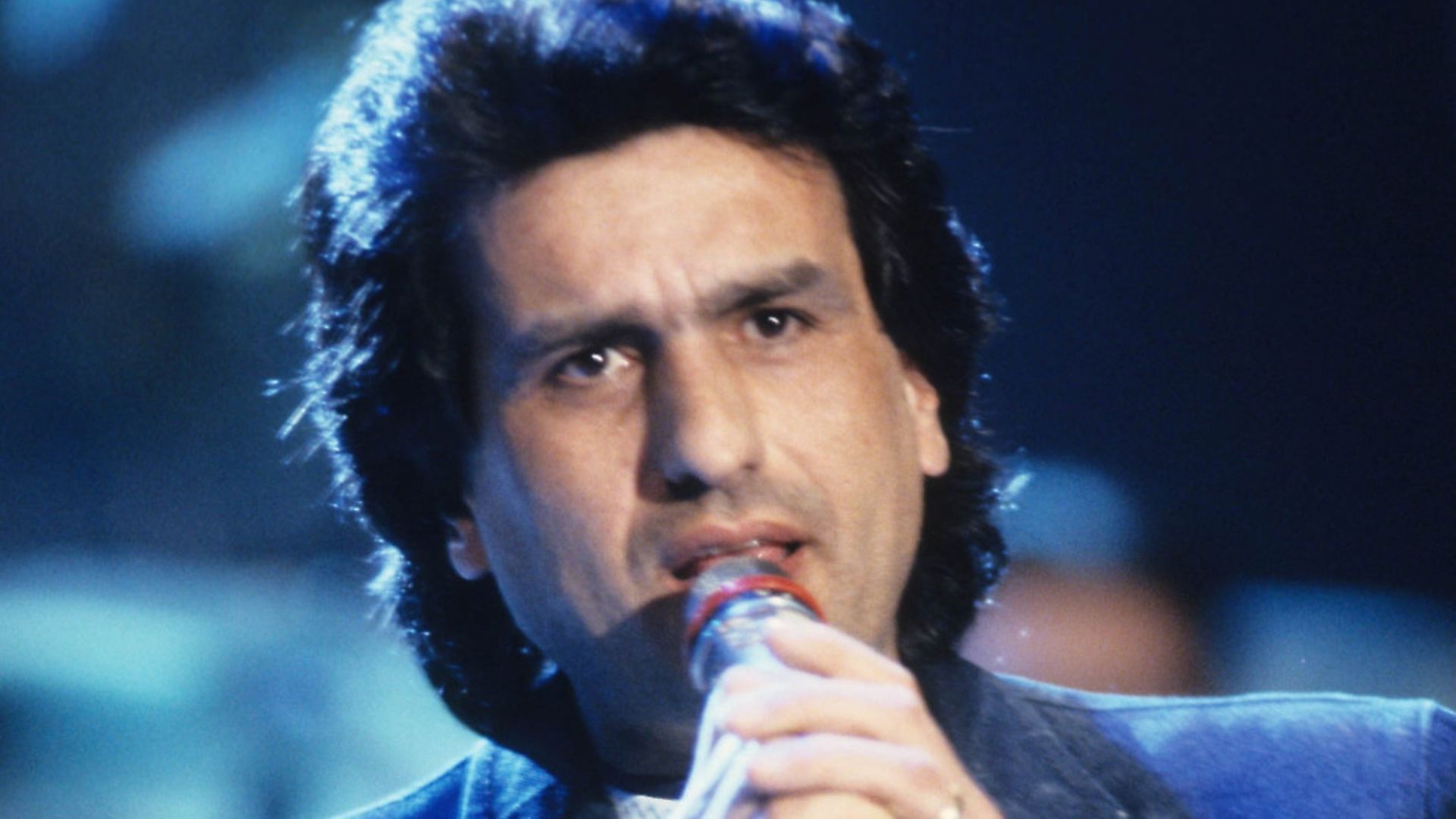

This is not an academic question: it happened in 1990. That year, Italy won with Insieme: 1992 (Insieme means ‘together’), a celebration of the single market. Its chorus, ‘Insieme – unite, unite Europe’, propelled singer Toto Cutugno to his heyday.

Insieme is not exactly a call to arms. It is a purely cheesy political hymn to cross-border romance: ‘You and I, under the same flag. For us, borderless love’. To the post-Brexit ear it certainly sounds odd that the single market could inspire such lyrics. (It is an interesting footnote of the contest that Insieme was awarded points by every country except Britain and Norway… a nation outside the EU but still bound by its rules.) And yet, songs like

Insieme represent what pro-European advocates have long failed to capture in the UK: the need for a sense of emotional belonging to Europe.

The most commonly-used argument for the British membership of the European Union has been one of economic convenience, which has been employed for at least 30 years. Not even the most ardent supporter of the British membership has dared to make European identity a substantial part of their argument. But if economic advantages have ceased to capture the interest of the British public, looking at that sense of belonging could be just what is needed to fight Brexit.

Insieme was not an isolated case: Liam Reilly, who competed for Ireland at the same Eurovision, sang Somewhere in Europe, a ballad portraying romance

during a European road trip. The German song, Frei zu leben(Free to Live), was also a hymn to unity: ‘Free to love, free to live, hand in hand, free but not alone’. In 1990, as the winds of democracy swept Eastern Europe, with the German reunification and totalitarian regimes falling, free movement became a notion worth celebrating.

For someone growing up in Italy at the time, that sense of positivity about the EU was inescapable, and it was not limited to songs. From 1988 to 1990, the Saturday prime time show on RAI 1, the country’s flagship state television channel, was Europa Europa. It was entertainment based on interviews, music, short documentaries, and international guests, each week from a different European country.

A joyful celebration of European history, traditions, differences and similarities, the show had millions of viewers every week. One feature became the equivalent of a meme: the presenters, Elisabetta Gardini and Fabrizio Frizzi, would call a random telephone number and award money if the person at the other end of the line answered by saying Europa Europa.

Gardini came to be identified with Europe: she went on to become a member of the European Parliament, spawning a political career which reached its pinnacle when she was appointed spokesperson of Forza Italia, Silvio Berlusconi’s party.

Schools also bought in to the united Europe idea, sometimes in bizarre ways. At the time, the repertoire of primary school music shows regularly included Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, Insieme, and foreign national anthems. European flag-waving was common, resulting in performances that looked like a kids’ version of the Last Night of the Proms.

Children’s television was not immune: according to audience measurement company Auditel, more than one million children throughout 1991 tuned in each week to watch the Wednesday evening show: Cristina, l’Europa siamo noi(‘Cristina: We are Europe’), a series starring Cristina D’Avena. A singer of theme songs for children’s shows, D’Avena’s popularity in Italy cannot be overstated: with a career spanning 30 years, she sold millions of records and

her gigs still regularly sell out, filling concert venues with thousands of people in their forties dancing to the tunes of their childhood.

Back then, the European Union theme was seen as a good PR move by music critics. A children book called Parliamo di Europa(‘Let’s talk about Europe’) circulated in those years as well. It had a few pages about each of the then 12 countries in the single market, presented by a fictional child from each nationality. In the early 1990s, weekly news magazine L’Espressogave away collectible imaginary replicas of ECU coins. The ECU was expected to become the single currency in the late 1990s the name ‘euro’ was chosen later), and people bought multiple copies of the magazine in a sort of European single currency fever.

These episodes may sound like pro-EU brainwashing, but there is a fine line between indoctrination and linking ideas with emotions. What these cultural activities did was to cement, for the Italian public, the sense of belonging to Europe. No one in the UK has consistently tried to build a strong sentimental bond with Europe. A successful pro-EU movement in Britain should aim to create a sense of celebration of, and belonging in, Europe, rather than just an acceptance of it.

The strong pro-European feeling of the 1990s opened many Italians to the possibility of living abroad. An entire generation called itself European, emigrated and moved between European countries, not just seeking better economic conditions but often motivated by a sense of wonder for the continent.

Feeling at home in many countries, these ‘cultural migrants’ enjoyed exploring different ways of life. Schemes like the Erasmus programme, for students, certainly helped in this. Here was an initiative showing that, although the EU was a sensible choice, financially and economically, for the continent, there was more than just a rational argument propelling it. There was an emotional one too.

It is true that the European Union did lose that early appeal, in Italy as well as elsewhere. This happened when its cultural, unifying drive, and its focus on a common identity, became obscured by financial and bureaucratic concerns. Increasingly focussed on the single currency, the politics of the EU ignored the symptoms of a changing world, which was about to enter years of uncertainty, as nationalism resurfaced. Zagreb, the host of that feel-good Eurovision 1990, would be engulfed in a horrific sectarian conflict within two years.

As the euro replaced national currencies, disillusionment with the EU accelerated in many places. In Italy, it has become the scapegoat for other problems, and in the election earlier this year the majority of Italian voters supported eurosceptic candidates. It is a sign that the country does share many themes with Brexit Britain – concerns over sovereignty and border controls, an idea that the national economy could do better on its own, and a dislike of the establishment – but it does not necessarily mean most Italians would vote to leave the EU.

The innocence of Insieme may have gone, but its sentiment is still strongly felt. And as pro-Europeans in Britain try to fight back from Brexit, they would do well to learn the song’s lessons, if not necessarily its words, and study what happened in Italy. Here, Europe stopped being something ‘cool’ when its supporters abandoned the idea of identity in favour of single markets, trade, bureaucracy, and currency. All these things are valuable, but ill not create a sense of passionate closeness with Europe. That’s where activists need to work: they should frame in a positive way what it means to be Europeans and show Britain that loving the UK is not incompatible with loving Europe; that being citizens of the UK is not incompatible with being citizens of the European Union; that feeling British is not incompatible with feeling European – because, ultimately, Britain belongs to Europe as Europe belong to Britain, Insieme.

Giuseppe Sollazzo, a dual-national British-Italian, is a civic activist and former government adviser on Open Data. He tweets as @puntofisso