Ibiza: The Silent Movie tells the playful potted history of the world’s most famous capital of hedonism. JASON SOLOMONS talks to the film’s director Julien Temple.

Like the residents and apartment holders near the Ushuaia hotel when its massive open air club nights opened, you might complain of the noise levels. This is supposed to be a silent movie, right?

Not a bit of it. Julien Temple, not for the first time in his long directing career, is having a sly joke. He even got Norman Cook, aka Fatboy Slim, to do the soundtrack, building up to those classic Ibiza dance anthems that took the music world by storm from the mid-1990s onwards, including Norman’s own banger Right Here, Right Now.

“Silent movies, don’t forget, always had soundtracks anyway,” says Temple, the former punk who went on to chronicle the Sex Pistols, direct Absolute Beginners and helm countless music videos for everyone from Janet Jackson and Neil Young to Whitney Houston, David Bowie, the Kinks and Dexy’s Midnight Runners.

Temple reveals that his grandfather ran an empire of silent film bands who filled the cinemas from Bristol to Penzance with musicians “sawing away every night and bashing at the keys to these images on screens in theatres in Taunton or Bridgewater”. With typical irony, he adds: “Of course, he went bankrupt overnight when the talkies came in.”

And Temple is now using the silent conceit to tell the history of Europe’s most famous holiday spot, from the arrival of the Phoenicians in 654 BC to the docking of the super-rich yachts and disembarking of the oligarchs in the mid-noughties.

It has always been, he says, as if this Balearic island was destined to be “a living experiment in utopia”. Although now, it’s where the “sunsets turn to money”. This is far more than a story of how beatniks, hippies and free parties turned into superstar DJs, supermodels and super-expensive beach clubs charging 500 euros for a day bed.

Temple’s ‘documentaries’ have long been unconventional and playful experiments, using archive and actors, blurring fact and fiction to build up layers and assemble a collage of images, sounds and voices. This results in an atmospheric portrait of the subject, an impression of the present arrived at via a history both real and mythical, using all the tricks of the trade to get there.

He’s recently done it in London: The Modern Babylon (2012), for Glastonbury (2006), and in his 2010 BBC documentary Requiem for Detroit. It’s where the ‘silent’ ideas comes from. The music doesn’t stop to allow talking heads to pontificate or reminisce – he simply lets images, music (plus those imaginatively-placed inter title cards) and dramatic reconstructions tell the tale.

He’s almost a psycho-geographist of Ibiza here, divining the ancient island’s wells, caves and famous red earth for clues as to where its legendary vibes and beats come from and where, inevitably, they are now leading it.

He sees repeat patterns in the fabric of Ibizan history – the Romans destroyed the place because Hannibal came from there; later, it was greedy hotel developers who hastily and secretly destroyed archaeological remains rather than delay their construction business. “I don’t think of the film as a doc, really,” says Temple, who admits he’s addicted to Mediterranean islands, from Corsica to Croatia to Stromboli, which thunders in the news footage on television behind us as we speak.

“It’s a cinematic essay, a provocation and perhaps in this case, an intervention. I’d like people who go [to Ibiza] this summer to stop and think for a second about the land they’re dancing on, or throwing up over.”

According to Temple, there will be over 100,000 planes landing in Ibiza over this summer. A plane is never far out of shot in his film, always creeping into the edge of the shot over dancers or bathers. “They spew fumes and vapours all over the island and create huge noise, noise which few people really hear, because it’s an isle of beats and noises anyway,” he says.

“So it made me think about tourism and what it’s doing to our planet and to human culture. Obviously at this time of the year, we are all guilty of it to a certain extent but there’s a sense now that tourism makes everything the same, to the point that: where you arrive might as well be where you left.

“Slowly, tourism destroys cultures, and I could see that happening in Ibiza, which is this most beautiful place but open to many episodes of darkness. It is, after all, a place of the night.”

Despite the ominous warnings, Temple has great fun with this film, using silent movie-style title cards to fill us in with facts and stories, using some eccentric dramatic reconstructions and even emojis where archive footage is not available – this is quite often, because, as you might imagine, there’s not a lot of pre-1960s Ibizencan archive footage. “I had to go to Madrid and Barcelona to find it,” he says, “and only then, there are just a few propaganda newsreels, beautifully shot, commissioned by Franco to show the glory of the peasant life he found there and its ancient ways.”

So a couple of Roman centurions oversee slaves piling up the salt on the flats of Salinas and various swarthy figures embody the Moors who irrigate and terrace the landscape, turning the White Island (originally because of the wealth salt brought, rather than cocaine, he’ll have you know) into a lush paradise.

The Phoenician God of Dance is Bes, for example, after whom the island is named and he’s played, in Temple’s imaginary reconstructions, by ex-Happy Mondays dancer Bez. And here I must declare an interest: I once flew to Ibiza for a film premiere and was sat next to Bez on the plane. The film was It’s All Gone Pete Tong, one of the few feature films actually shot on the island, so they showed the film on the plane and took us all up to a private villa for an all-night rave before flying us back the next morning, non-stop.

Bez threw popcorn at me and sprayed beer over the rest of the plane for most of the film, making my task as a reviewer somewhat tricky, although, you know, I managed. He was incoherent yet hilarious, if slightly dangerous company on a packed plane full of ravers, DJs and drinkers.

I don’t know what happened to Bez after we landed that night. I can’t remember him on the dancefloor of that villa – but then that was the night, and the dance floor, where I met the woman who, two years later, became my wife.

We went to Ibiza all the time after that, but since having kids, can’t afford it any more. Talking of which, actress Claire Davis – a regular dancer at Ibizan club Manumission – also plays the god of fertility, Tanit, to whom much homage is still paid around the island in various signs and names.

Temple taps into the ancient sexiness of Ibiza, a place of retreat and exile, a place of hedonism and escape, paying as much attention to historical fact as to myth. Actually, maybe more to myth. “People always like to wink at you and say ‘ooh… the Romans held orgies here’,” he says. “Although of course the Romans held orgies everywhere.”

There’s a lot of bluster spoken about Ibiza, about its ley lines and geographic positioning. “Oh, it’s famous for making stories up about itself,” says Temple, “but I wouldn’t want to stand in the way of that. So many people claim to have invented it, from the three DJs (Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling and Nicky Holloway) who reckon they started it all, to every ex-pat out there who has their own story, so much so, that these myths become part of the truth the more you dig.”

The distinctive rock off the west coast, Es Vedra, is spectacular to behold and it is rumoured to be one of the most magnetic places on earth. Temple’s film mentions the repeated rumours that aliens are supposed to have colonised it and that sirens are rumoured to have lured sailors to their death – cue clips of Kirk Douglas as Ulysses, inter-spliced with sexy topless women in bikinis. It’s that sort of film.

Hannibal and Christopher Colombus were (perhaps) born in Ibiza; the young Sid Vicious grew up there, child of a fugitive hippie. When America was discovered, the little Mediterranean island lost its importance as a trade route pit stop and fell prey to a long history of poverty, piracy and smuggling. Things began to turn as Dadaists and philosophers such as Walter Benjamin (played in Temple’s imaginary reconstructions by Chas Smash, of Madness, and now an Ibiza resident) sought refuge there from Hitler’s Berlin in the 1930s, and found their own kind of paradise.

“They opened the first nightclub in a disused windmill and invented topless bathing,” says Temple. That was before Franco took a liking to the place and it became a battleground in the Spanish Civil War. In a rather startling mid-section, Temple details how Formentera, the little idyllic island off the coast, became a concentration camp. This is bloody and dark passage in the movie, with archive of peasants, pig slaughter, soldiers marching through the cobbled streets, gun ships in the harbour, Guernica-style bombings and the Gestapo taking over Ibiza Town in the Second World War.

Many of them hid out in the hills once the war ended. Indeed, there were always stories of them re-opening their fincas (estates) as ecstasy factories in the 1980s, and the last of the hidden Nazis was rumoured to have been spotted in Ibiza as recently as 2006.

Temple’s mood lightens as the ‘beatniks and dopers’ of the 1950s take over the Domino bar; however, there is always an uneasy alliance with the authorities, the repressive Franco regime who are nominally in charge of the island and the families buying up coastal land for beachfront development – initially, fine by the locals, who prized the farmable, fertile inland plains far higher, but who soon realised they’d been duped.

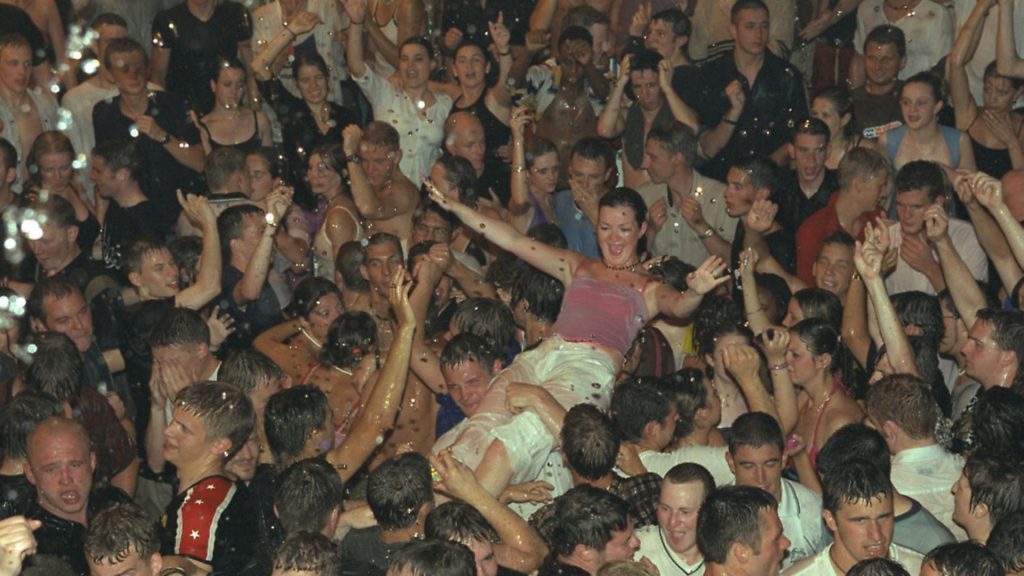

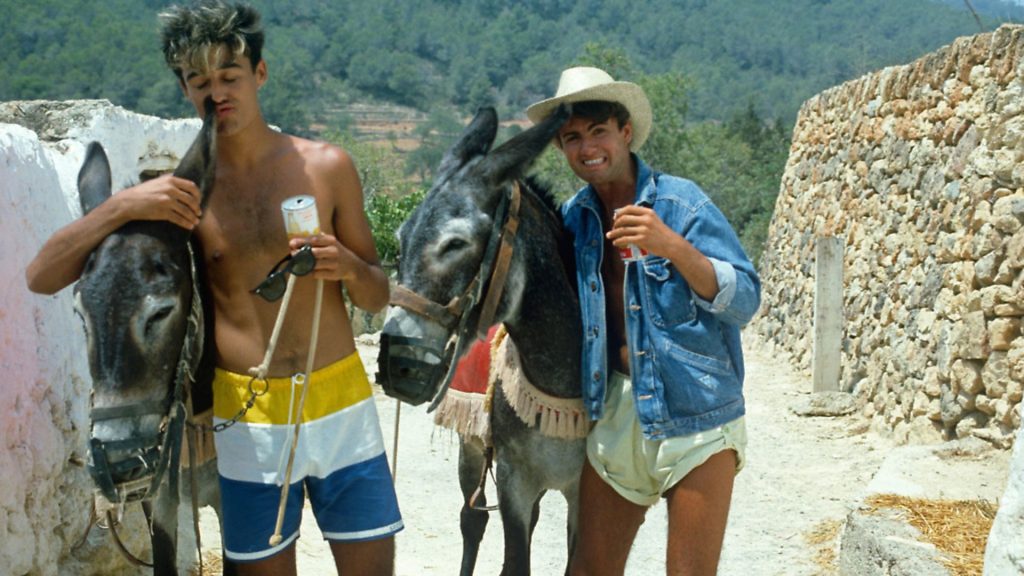

And it’s this balance that remains even as the hedonism ratchets up – Franco mining the island for mass tourism; the 1980s Ibiza of Freddie Mercury, Club Tropicana and Grace Jones at Pikes; the clash of ancient farmers still ploughing the earth inland while Scouse and East End drug dealers were setting up bases on the beach; the heyday of free parties and the 1990s Balearic beat; the sunsets at Cafe del Mar and the whole ‘chill out’ scene; the Russians building vast mansions in the rock; package tourists vomiting on the San Antonio streets; 40,000 ecstasy pills taken every night and kids who won’t pay 10 euros for a bottle of water and end up in hospital.

The clubs and super clubs, the yoga retreats and Buddha heads, the constant Ryanair flights, the heaving crowds dancing round a pool, the light shows, the sunsets, the cleaners and waiters who can’t afford the rent and who live in caves – all of these get a look-in in Temple’s film.

Will this era of clubbing now crumble, too? Will its ruins be reclaimed by nature, like the huge nightclub overrun with creepers and graffiti Temple finds in a forgotten corner above St Josep?

“The approach now is a VVIP one,” he says. “To try and get rid of the cheap package holidays and drinkers, but that has seen the prices rocket to mind-watering levels. Some people have gotten very rich out of it and very protective – about half the island is all for it, I’d say, where the other half feel left behind and exploited.”

There is still much darkness there. There are stories of executions, gangster killings, mob revenges, terrorists on the run, drug deals gone rotten and whole mansions being blown up. “Money can poison a whole island very quickly,” warns Temple, “and there’s a lot of money in Ibiza – it’s gone from being the poorest place in Europe to the richest, so you can imagine the shock to the whole culture.

“There are still a few farmers in the north who claim never to have left the island. I even met a couple who told me they’ve been there their whole life and never seen the sea.” Admittedly that’s a bold and unlikely claim, but it’s entirely in keeping with the island’s gift for self-mythology, a talent clearly not limited to drug-addled clubbers. Or to filmmakers, judging by this hugely enjoyable romp and rave through the history of one of Europe’s hottest, darkest and sexiest summer spots.

Ibiza: The Silent Movie premiered at Cineramageddon at Glastonbury and is now on general release