As politics continues its campaign to make satire redundant, CHARLIE CONNELLY finds mixed results in an attempted fightback by one of British literature’s biggest names.

As British politics and society lurch from one piece of tragic slapstick to the next the phrase “satire is dead” is frequently heard, usually accompanied by a weary shake of the head. With our once-proud nation fallen way beyond self-parody into a cavernous dignity-vacuum of barely believable incompetence, it’s made the job of the satirist all but impossible. How can you lampoon something that is so expertly lampooning itself? How can you tease out the flaws and foibles of our leaders when they’re worn so brazenly by the subjects themselves?

British satire has a long and noble tradition, snooks having been cocked at the priggish and powerful from the broadsides and pamphleteers of the 17th century right up to modern masters like Peter Cook and Chris Morris.

Satire as a literary genre arguably originated in Ireland with Jonathan Swift, whose sideways looks at contemporary society set the tone across the Irish Sea for a bold and brave string of writers from both these islands to administer pies in the face to successive generations of corrupt, dishonest and pompous public figures.

The satirist’s art has never been under greater threat than it is today, however. Not only do we have the least intellectually gifted political class since we spent our waking hours banging rocks together, the cycle of overblown idiocy grows faster day by day.

As I write this it’s just been leaked that the government was considering a plan to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland by creating a giant border 10 miles wide while Katie Hopkins has tweeted about how disappointed she is never to have been sexually assaulted by the current prime minister. By the time you read this both incidents are likely to have been forgotten, buried beneath yet more jaw-dropping buffoonery.

In the great circus of politics, Brexit has long provided the old-fashioned fire engine careering around the ring with its bell clanging and clowns hanging off the ladders and there’s no sign of the brakes being applied anytime soon.

The sheer quantity of material, the pace at which it arrives and the fact the people providing the material are so pathologically ridiculous means that satire doesn’t really know where to go any more. Its only home now, the only place that can keep up with the pace of events and bang out pithy comment before it goes stale, is Twitter.

Literature has the toughest task of all. A book takes months, often years between a writer cracking their knuckles and opening a new Word document and finished copies hitting the shelves. It’s hard enough publishing considered Brexit analysis in long form without it becoming obsolete almost immediately, but satire, which depends on quick wit and the freshness of its material, doesn’t stand a chance.

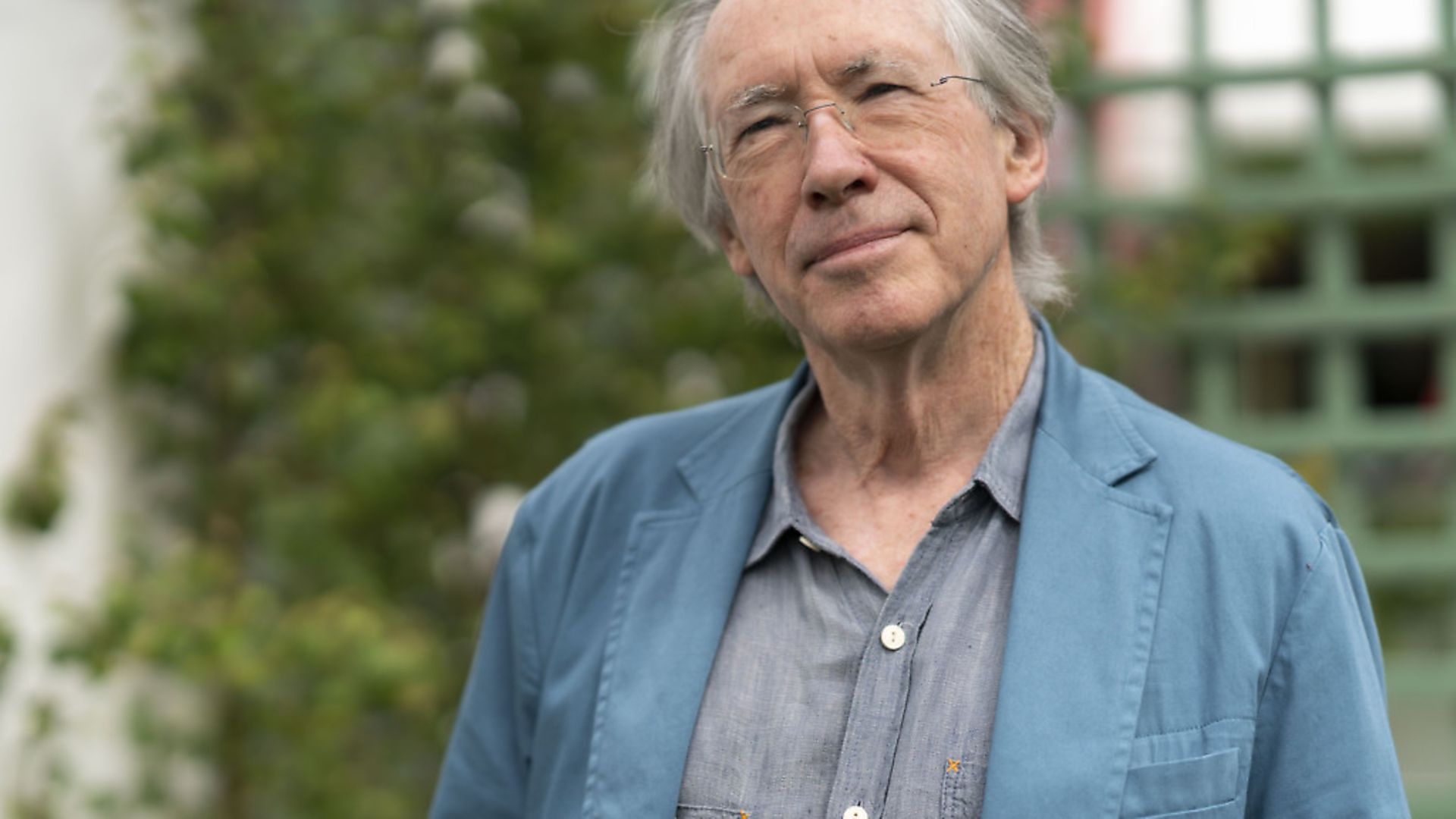

This hasn’t stopped Ian McEwan from having a go, however. In July this year he was so frustrated by Brexit and the parlous state of our political culture that he sat down and began writing something. It wasn’t necessarily intended as a book – it was only three months since his novel Machines Like Me had appeared – but by the time September gave way to October it was a fully-formed novella available from all good bookshops.

The Cockroach faces many challenges, most of which are outlined above. Add to those how the speed of its production has not allowed the writer time for rumination, rewriting or reshaping in the rush to have the book available as quickly as possible and it’s a brave book to even attempt, let alone see to fruition.

“As the nation tears itself apart, constitutional norms are set aside, parliament is closed down so that the government cannot be challenged at a crucial time and ministers lie about it shamelessly in the old Soviet style, and when many Brexiters in high places seem to crave the economic catastrophe of a no-deal, and English nationalists are attacking the police in Parliament Square, a writer is bound to ask what he or she can do,” said McEwan. “There’s only one answer: write.”

The result is, well, a mixed bag. The eponymous creature is a nod to Kafka’s The Metamorphosis in which a salesman named Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning to find he has turned overnight into an insect, in some English translations a cockroach.

The Cockroach opens in similar fashion, reversing the transformation so the insect wakes up to find that not only has it turned into a man, the man in question is the prime minister and the prime minister has a bit of a hangover.

The prime minister, in a nod to Gregor Samsa, is called Jim Sams. He has fair hair, he’s a bit scruffy and says things like “tops” and “jolly good” so there are no prizes for guessing whom he is supposed to be. Most importantly, however, he’s now inhabited by a cockroach.

The events described in The Cockroach are set in the present day. The nation has become febrile and divided in the aftermath of a referendum that has sown discord and division and grown from a binary vote on a single issue into a battle for the very soul of the nation.

It’s not Brexit that’s done the damage, however, it’s a new economic system called Reversalism in which the circulation of money is, well, reversed. Instead of being paid for their labour workers pay their employers but are in turn paid by retailers and service providers to take away their goods and services.

It had begun as “a thought experiment, an after-dinner game, a joke, the preserve of eccentrics, of lonely men who wrote compulsively to the newspapers in green ink”, but before long a Reversalist Party had emerged, gaining significant political traction by anchoring its creed to a platform of populist anti-elitism.

Opponents were deemed ‘Clockwisers’ – because they wanted to keep money moving in the traditional direction – and the nation was split down the middle on those lines.

The events of this short book – exactly 100 pages long – take place between the vote and the implementation of the Reversalist system at a time when Sams is determined, despite vocal opposition, to push through the policy come what may.

He stitches up members of his own cabinet and pounces on any opportunity to stoke nationalist fervour, such as a fatal accident in the English Channel that leads to diplomatic exchanges with France that are ham-fistedly aggressive from the British side and greeted with baffled dignity by the French.

All very resonant of current events: There’s even a dash of prorogation and a healthy dose of abusing the partnering system for votes in the Commons (something that made headlines what seems like about four years ago now but was probably just the other week).

McEwan packs a hell of a lot into his 100 pages – there’s even an oafish US president with a limited attention span who tweets a lot – and there is some elegant writing here reminiscent of his early, darker work.

The opening passage in which the cockroach wakes to the realisation he’s inhabiting the body of a human being is artfully done, for example: “Rather than letting his tongue hang out beyond his lips, where it dripped from time to time onto his chest, he found it was more comfortably housed within the oozing confines of his mouth.”

Yet for all The Cockroach is an interesting idea in the hands of one of our greatest living writers, somehow it doesn’t really take off. Mostly it’s because the Britain we live in today is one big satire, a country indulging in the ultimate self-own of harming itself grievously while pretending it’s on the road to greatness and prosperity.

Last week, for instance, we were treated to the spectacle of Priti Patel addressing the Conservative Party conference, smiling broadly as she boasted of ending the free movement of people. This was an actual serving British home secretary grinning and oozing pride about reducing the rights of every single British person, young and old, rich and poor, and earning cheers and applause from some of the actual people losing those rights.

When the party of government is punching the air and high-fiving about taking rights away and the victims are celebrating like it’s a late winner in a cup final, how can anyone effectively satirise the Britain in which we find ourselves?

For that reason alone McEwan faced a hell of a task and it’s not one he’s risen to entirely convincingly. Towards the end of the book it becomes clear that the rest of the cabinet have also been taken over by cockroaches and as the country careers towards its inevitable demise they decide their work is done, shed their human forms and march back to the gutters of Westminster whence they came.

Their motives are never clear, however: if McEwan is saying our pro-Brexit government is a bunch of cockroaches, a.) it’s a pretty ham-fisted bit of satire and b.) the referendum in his novella had already happened and the government was enacting it anyway, so why the cockroaches?

There’s little in the way of insight either, surely the key aim of good satire. When Sams makes a nonsensically blustery speech to the UN and the chamber rises in appreciation, a French diplomat cannot understand why the delegates are standing and applauding.

“‘Because,’ his older companion explained, ‘they detested everything he said’,” writes McEwan in what feels like it should be an ‘a-ha’ moment of perspicacity as to how the world really works but is too trite to be a satirical checkmate.

The Cockroach feels like the satire could have gone a lot further than it does. This could be because the real world is so cuckoo-clock bonkers these days, but there’s a restraint to the writing and a tangible reluctance to really get the teeth crunched fully into the subject matter.

It feels safe, which can be fatal for good satire. It’s also a book that is quite pleased with itself, as if based on a joke that would raise chuckles at a north London dinner party but outside certain postcodes there’s a danger of coming across as too self-satisfied for its own good.

While The Cockroach has moments of insight and a few devices that work very nicely, ultimately it falls just too short of being an effective satire. Laugh out loud moments are hard to find but good satire doesn’t always need punchlines, it’s the reluctance to really bite into the subject that’s most unfulfilling here. When the world is as mad as it is today then satire has to find somewhere else to go but McEwan here always seems to step back from the brink. When Sams meets the German chancellor for a discussion on post-Reversalist trade, for example, she listens to his madcap scheme and asks why he is doing this, tearing his nation apart, pretending friends are enemies. Sams thinks about this.

“‘Because'”, writes McEwan of Sams’ conclusion. “That, ultimately, was the only answer: because.”

Not so much a satire on Brexit Britain then, more the depressing reality of the plain truth.

The Cockroach by Ian McEwan is published by Jonathan Cape, price £7.99