We Dutch used to make fun of the Germans and admire the Brits, says Vanessa Lamsvelt. Now, we find ourselves laughing at, not with, the UK

Growing up as a northern European citizen in the 1980s and early 90s the world was so much simpler. The European Union consisted of only 12 countries, you were a traitor to the EU economy if you bought a Japanese manufactured car and a lot of us would have an aversion for anything looking or sounding German. From here, in the Netherlands, you were taught to look for inspiration and ideas westbound, not east.

Don’t believe Dutch people who say they never showed a German who asked for directions the wrong way. We all did. Being a granddaughter of a primary schoolteacher who lost all her Jewish pupils during the war, I was brought up with a strong anti-German sentiment. We took pride in making fun of the Germans. A highlight was 1988, when Holland beat Germany at the semi-finals of the European Football Championships and Dutch defender Ronald Koeman wiped his bum with Olaf Thon’s shirt in front of German fans. Germans we were taught, were the outcasts of Europe; loud, rude and clunky. A sentiment that ran deep. The mere sound of a tourist speaking German would cause agitation.

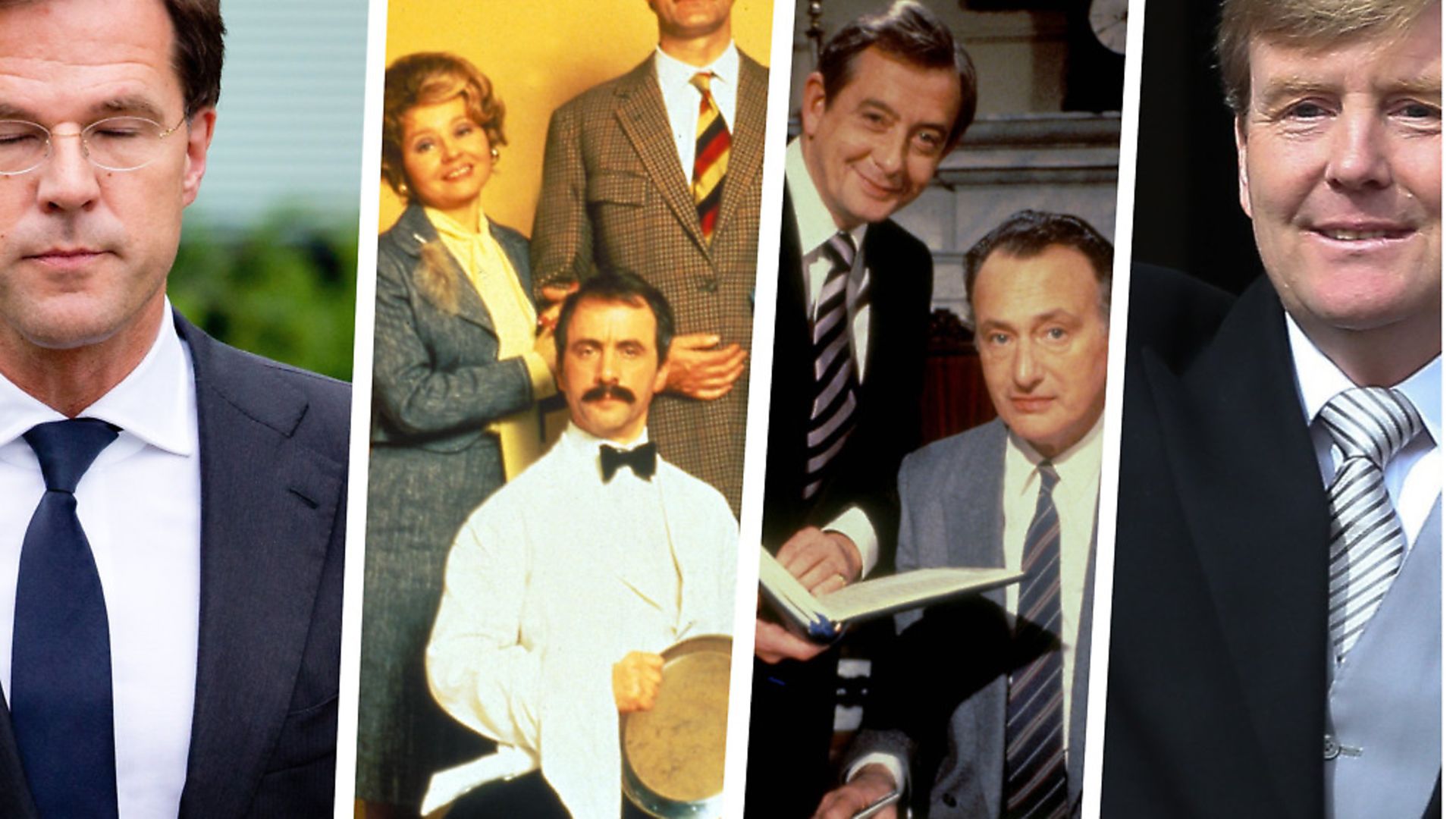

What a different view we had of our neighbours over the sea to the west; civilised, polite and kind. The British, they were the people we related to, we were told. Of course they too had their peculiarities; living on an island they had developed some strange habits. They drank lukewarm beer and ate tinned beans on toast. But still, we felt culturally close and we shared the same sense of humour. In fact, we actually looked up to the British – their music, their writers, their actors. If you wanted to make an impression at work you would mention in passing that you had seen the latest episode of Yes Minister on the BBC, and you could always score points by impersonating John Cleese and his Fawlty Towers’ ‘don’t mention the war’ line. Hopelessly stereotypical? Of course, but it’s these strong images that stuck in our continental minds.

Fast-forward 20 years, and you can still boast by citing a British author or by saying you saw Newsnight the other night. But things do seem to be changing. The aversion that my generation felt towards Germans has dissolved over the last 10 years and younger generations now feel more and more connected to our neighbours in the east. With the UK’s decision to leave Europe, the natural connection and understanding we northern Europeans feel towards Britain is in danger of slowly drifting away. And not for the first time.

Throughout history our bond with the UK has had it’s ups and downs. It wasn’t very amicable during the 17th and 18th century; during four Anglo-Dutch wars we fought each other at sea over trade and overseas colonies. It got better during the 18th century when Napoleon was defeated and the Dutch statesman Gijsbert Karel van Hogendorp declared the British ‘our natural ally’. But that natural alliance vanished in the 19th century during the two Boer Wars in South Africa. The tides turned again during the 20th century.

The Second World War changed the relationship for good. Britain offered shelter to the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina and to the Dutch government. Most of the ships of the Royal Dutch Marine were safeguarded in England and a few Dutch pilots who managed to flee the Netherlands joined the Royal Air Force and fought in the Battle of Britain. The most famous was resistance hero Erik Hazelhoff who, better known as the Soldier of Orange, joined the RAF in 1942 – not before bluffing his way through an eye test which he never should have passed as he actually needed glasses. And of course the British played a crucial role in liberating the Netherlands from the German occupation.

The bond shaped during those war years stuck and over the last decades it expanded on many different levels. In business, multinationals like Shell and Unilever joined forces. On a military level the British and Dutch Royal Marines formed an alliance – though our men do have to live with the British calling them ‘Cloggies’, they too using stereotypes, implying that we still walk on wooden clogs all day. On a royal level our King Willem Alexander is the 850th successor in line to the British throne. And in politics, the Dutch always found a close ally in Britain when it came to NATO, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe and, until recently, the European Union.

In European life we value the British-Dutch axis. The Germans are too rigid, the French too statist. The British are the ones who we are more in tune with when it comes to monetary policy and also seeing Europe mainly as an economic project, and not an ever closer political union.

Our current Prime Minister Mark Rutte is a self-declared Anglophile. Pre-Brexit he would gush over his UK counterpart David Cameron and openly declare his love for England. He likes to reads books on British politics and in his speeches he often uses English words. We make fun of it but at the same time we don’t mind. 87% of us speak English as a second language. A lot of us have studied in England through cultural exchange programmes or worked for a few years on the other side of the Channel. During these times we have built friendships and relationships with the British, experiences which we absorbed and took home.

Then came the shock result and vote for Brexit. In the run-up to the referendum the comparison of Brexit with a divorce had so often been made. They were merely words then, but not anymore. As a country we felt rejected by an ally who we admire and trust. It wasn’t personal we were told, but it did feel that way.

Rutte has said that he ‘hates Brexit from every angle’. He also says that he hoped there will be ‘some form of UK membership or relationship with the internal market’. But his tone has clearly now changed. The amicable relationship that Rutte shared with Cameron has been replaced by a cautious and calculated approach towards Theresa May. As has the view of EU-chief Frans Timmermans, another Dutch Anglophile, who recently mocked Britain’s vision of a post-Brexit world by comparing British politicians to Monty Python’s Black Knight. Until recently Dutch politicians wouldn’t publicly make fun of their British counterparts but now they are seeking new allies. ‘If people talk about the French-German axis, then I think ‘what about the French-Dutch axis’,’ Rutte said recently. ‘I want to help shape Europe and you need alliances for that.’

But what about the alliance between ordinary Dutch and British people? Ask a Dutchman and he will still prefer to share a beer with an Englishman over a German – we might not laugh at the Germans anymore, but laughing with them is, for a lot of Dutch, still too much to ask. But it’s not hard to imagine that we too will eventually shift our focus to Germany and France in the event of a Hard Brexit, not least because it will be easier to study in a EU member state and because multinationals will have moved from London to Frankfurt and Paris.

Of course we won’t suddenly cut off friendships, discard British literature or not laugh about the understated humour we love so much. But the admiration we felt for so many decades is fading. When a partner unilaterally ends a relationship you automatically start to scrutinise that relationship. The things you used to love about the other party are no longer so endearing.

You see things differently and weigh them up differently. Boris Johnson is an example. When the UK was still part of the European team, in the period before Brexit, we thought that he was a charismatic and strong politician and that he could get away with the gaffes he made. We would even wonder why we don’t have these colourful and eloquent people in Dutch politics. But since Brexit his jokes suddenly don’t land in the same why they used to. His humour makes him look like a clown. What was first seen as funny is now seen as insensitive and very gauche coming from a foreign minister.

Angela Merkel on the other hand used to be mocked for being boring, stern and unnoticeable, but in recent years ‘Mutti’ has become popular amongst us continentals. In a world that is becoming more and more complex we value a leader that takes the problems we face seriously. The difference with her British counterpart Theresa May couldn’t be greater; she is seen as a leader who uses big, but ultimately meaningless, phrases like ‘Brexit means Brexit’ and who claims to be strong and stable but can’t deliver. She is weak and wobbly, and making Britain look messier every day.

That mess is starting to become the new status quo. As an outsider it seems British politicians are leading their people blindly towards the edge of the cliff. There might be a big master plan that we can’t see, but it doesn’t feel that way.

As an abandoned partner there comes a point when you just don’t understand it anymore and you start to lose respect. One of the things we always admire in the Brits is their understated sense of humour and the ability to make fun of themselves. But to be able to do that you need to be taken seriously. And the decisions that Britain has been taking over the last year are very hard to take seriously.

Vanessa Lamsvelt is the Brexit correspondent for EenVandaag, a news and current affairs programme on Dutch national TV. From 2010-2015 she was based in London and the UK-correspondent for RTL Dutch TV 1.0.0.19