John Heartfield pioneered the use of art as a weapon of politics. JAMES BROWN reports on a new show which underlines how relevant his work remains

In a bright double-fronted gallery on a dark wet night in an area of the East end of London, where gastro pubs and tiny European-style bars rub up alongside boxing gyms, tanning salons and vape shops, and gentrified workers’ terraces snuggle next to sprawling concrete estates, a woman is delivering the sort of urgent defiant speech you used to hear a lot of the last time right-wing nationalism was on the rise in Britain.

Back then, the racist notes came from marginal hate groups like the National Front and British Movement. Nowadays they are to found in the national press and on the BBC from mainstream political figures.

Curator Carla Mitchell thanks us for our attendance at the Four Corners Gallery, stresses the importance of fighting fascism, and then introduces John Hyatt, a professor of contemporary art at the Liverpool John Moore’s School of Art and Design.

It’s a long title for a man I spent my late teens in the mid-1980s travelling round the country with, when he was lead singer with The Three Johns, a popular left-wing, post-punk, agit-prop group who made the front of the NME, appeared on The Tube and recorded many John Peel sessions.

I was a fanzine writer and aspiring music journalist then and one of the many places we visited was Berlin, where, among the postcards of the Wall going up and Russian and American tank drivers staring at each other across Checkpoint Charlie, we found others featuring the anti-Nazi images created by the German artist John Heartfield.

These stark, black and white images of religious, political and icons mixed with depictions of war, poverty and death were instantly familiar to anyone who had records by the Sex Pistols, Dead Kennedys or Crass in their collections.

They were the template for the graphic imagery of punk, the inspiration behind the graphic art of Buzzcocks sleeve designer Linder, and yet predated them by decades.

They were even more compelling when we discovered they’d been created when Adolf Hitler, not Margaret Thatcher nor Ronald Reagan, was in power.

Heartfield is the reason we are at the crowded gallery in Bethnal Green listening to Hyatt explain the provenance of the German artist’s work on the walls. Looking round the gallery it seems strange to me that this vital, brutal art isn’t sitting somewhere prestigious and swanky in London’s mainstream establishments, that there aren’t television cameras or newspaper arts editors present, but fair play to the Four Corners for flying the flag of anti-Nazi art.

While the anti-capitalist, anti-war and anti-Hitler tone of the work is apparent, the origination of the prints themselves is worthy of explanation. Planning an exhibition linking Liverpool’s political history, the 1968 Paris riots and Dada-inspired Situationist movement, Hyatt was told by a colleague, professor Colin Fallows, that he had heard one of the founders of the Berlin Dada group – the great photo-montage artist John Heartfield – had visited Liverpool University shortly before his death in 1968 – in East Berlin, where he lived – and that there were rumours he had left some work for the students. Intrigued, Hyatt went in search of them.

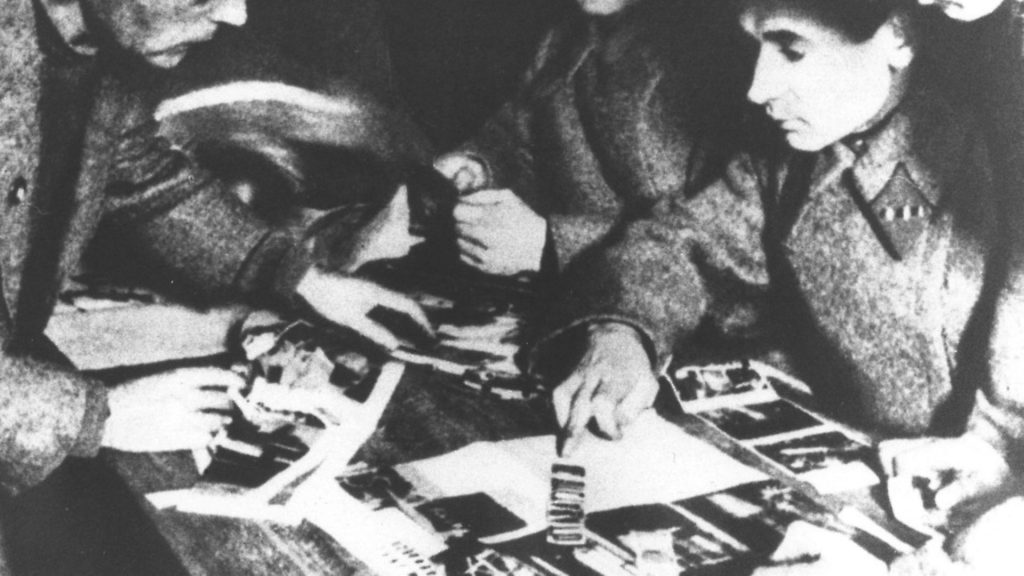

“Colin thought that John Heartfield’s widow, Gertrud, had gifted some posters to the School that must now be somewhere in the university ‘special collection’ archives,” Hyatt recounts. “The LJMU archive is extensive and rich, but with the aid of Valerie Stevenson and Emily Parsons from the library we tracked down a greatly distressed box in the bowels of the collection.

“The box was made of cheap East German 1970s cardboard, but the prints themselves were relatively undamaged. I could not believe what was in that innocuous box: 33 of John Heartfield’s finest anti-Nazi, pro-Communist, 1920s and 1930s photomontages and collagraphs. Better than this, if it could have gotten any better, they had been designed to be an exhibition and had labels in four languages. It had clearly been exported by the Cold War East German Communist state as a propaganda tool – the labels were subtly anti-west and anti-capitalist.

“I have since met someone who saw Heartfield’s talk in 1967,” says Hyatt, “who said that even as an old man Heartfield was still angry, animated and shouted about the atrocities of the rise of National Socialism in 1930s Germany.”

Heartfield led a life of relocation due to political oppression and street activism and used it all to shape his work as one of the fathers of photo-montage propaganda.

Born Helmut Herzfeld in Berlin in 1891, his parents fled to Switzerland and then Austria when he was four years old, after his father, a socialist writer, was found guilty of blasphemy.

Four years later his parents abandoned Helmut and his brother and sisters for good, in a house in woods, leaving them to be passed from relatives into a childhood of strict Catholic children’s homes.

The experience sharpened Heartfield’s sensitivity to the injustices of the world. His brother Wieland said of the situation: “My brother, who was five years older, experienced the full impact of the loss. For four days and nights he was alone with younger siblings in the isolated hut. The eight-year-old never thought of going down into the village. Frightened and helpless, despairing more completely with each passing hour and day, he ran into the woods again and again to call just one word: ‘Mother’.”

Heartfield began his professional life studying art and design in Munich before going on to work for a commercial printing company. He was aged 23 when the First World War broke out, but feigned insanity to escape conscription. He subsequently changed his name to John Heartfield as a stand against the anti-British fervour of the day.

With his brother Wieland and artist George Grosz (who also Anglicised his name, from Georg Groß) Heartfield set about publishing underground anti-establishment paper New Youth using headlines cut up to avoid censorship rules.

After the war Germany was impoverished and lacking a clear political structure. The trio joined the German Community Party (KPD) and took part in the 1919 Spartacist uprising.

At the time, the Dada art movement was taking shape – attacking the pointlessness of contemporary life – and the two brothers and Grosz set about combining art and politics in a flurry of pamphlets, artworks, posters and publications.

Heartfield’s first photomontages appeared in 1919 in a title called Everyman His Own Football (Jedermann sein eigner Fussball). Although occasional combinations of photography and painting had appeared since the late 19th century it was Heartfield who sharpened it into a tool of propaganda.

Other figures on the Berlin Dada scene like Hannah Hoch, Johannes Baader and Raoul Hausmann were involved in its evolution but Grosz attributed invention of modern photomontage to his friend and creative collaborator: “When John Heartfield and I invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o’clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it.”

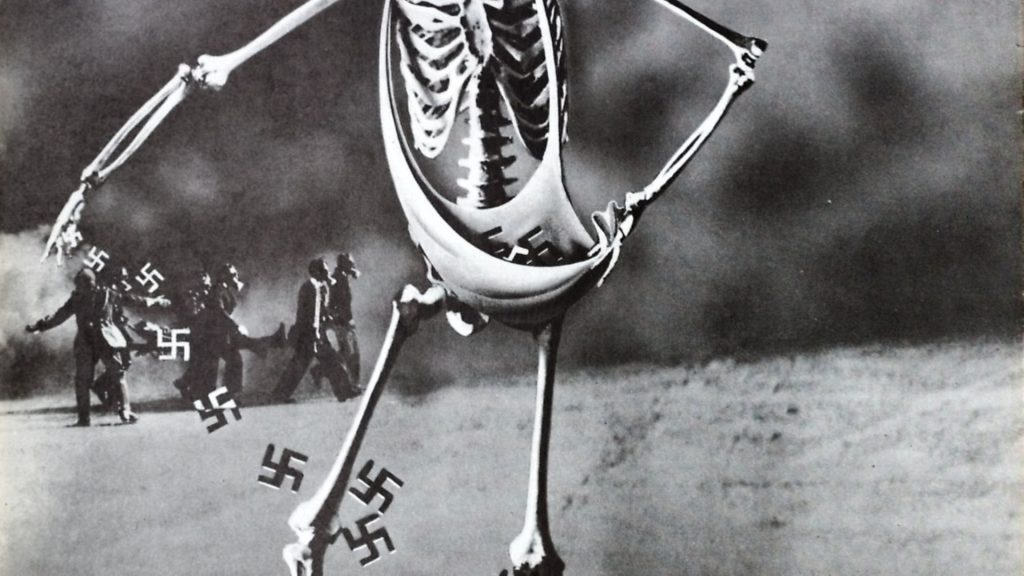

As the Weimar Republic crumbled into life, Berlin’s creative underground thrived. Heartfelt designed book sleeves, theatre sets, and posters for Bertolt Brecht, among others. He built his reputation by creating provocative left-wing book jackets and in 1924 used a bookshop window to display Ten Years Later – Fathers and Sons featuring a line of skeletons overlooking a parade of army cadets. It was his first significant anti-war piece and drew large crowds outside the Malik Verlag publishing house, which the police moved on.

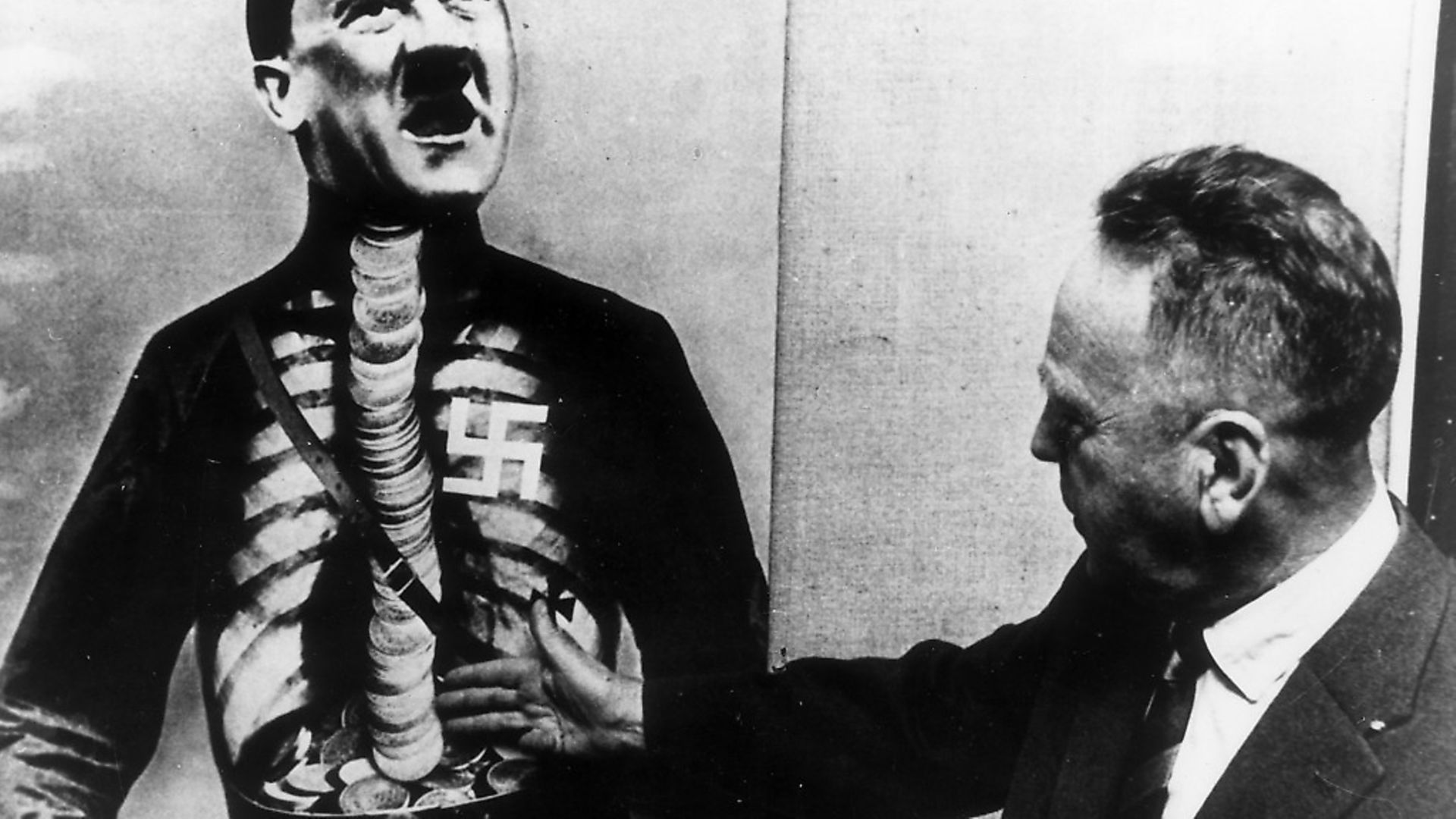

Heartfield’s most recognisable work appeared in Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (AIZ, the Workers Pictorial Newspaper) between 1930 and 1938, when he created more than 200 (often cover) images focusing on capitalism, war and the rise of the Nazis. The publication had a weekly print run of 500,000 and Heartfield’s images became the visual representation of the anti-Nazi movement.

In 1932, a series of elections took place amidst an atmosphere of mass unemployment and political instability that saw violent street battles between left and right.

As the political atmosphere of Berlin became more dangerous and destructive so Heartfield’s work became darker and more striking. In War and Corpses – The Last Hope of the Rich a top-hatted hyena with a “For Profit” medal round his neck, stands greedily over a landscape of barbed wire and dead German infantrymen.

Having prominently portrayed Hitler as a puppet of capitalism, the Nazis were keen to censor Heartfield when they came to power in 1933. AIZ relocated to Prague and Heartfield quickly went too. On Good Friday, 1933, the SS broke into his apartment in Berlin. He escaped by jumping from his balcony and hiding in a rubbish bin, before walking over the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia.

It was while working in Prague that he placed the body of a naked martyr across the swastika and portrayed a German family eating ballbearings and bicycle chains (Hurrah, the butter is finished) in response to Goering’s 1935 announcement that “iron makes an empire strong, while butter and lard only make people fat”. As the situation in Germany darkened, Heartfield’s work became more famous across mainland Europe. It also meant he had to move on, again. In 1938 – by which time he was number five on the Gestapo’s most-wanted list – and with the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia imminent, he moved to Britain.

Heartfield was less well known in the UK and his art struggled to find an audience with a British public more used to seeing Hitler portrayed as a clown. Looking for creative support Heartfield helped establish emigre anti-fascist organisation the Free German League of Culture (FGLC) who in turn organised his first British one-man exhibition One Man’s War Against Hitler and a short-running Weimar-style political cabaret in London’s West End named Four And Twenty Black Sheep.

Despite his clear political leanings Heartfield was still a German, viewed with suspicion, and was interned for six weeks before being released on health grounds. Significantly, he was forbidden from working until 1943 when he began producing jackets for nature books.

He remained in the UK after the war but in 1950 he moved back to (now, East) Germany with his (third) wife, Tutti Fietz, who he’d met through the FGLC.

Despite his Communist Party membership during his 20s, his long spell living in England meant he was met with suspicion by the East German authorities. It was not until Stalin’s death in 1953 that cultural control softened slightly and he began to be welcomed as an artist again, when Brecht encouraged his membership of the East Berlin Academy of the Arts.

Gradually, as the 1960s progressed, a new generation of Germans and fellow Europeans began to see Heartfield’s work not only as a valid reflection of where German had gone wrong 30 years earlier but also as applicable commentary on more contemporary conflicts, such as the Vietnam War. His images were adapted and formed a direct link between the street demonstrations of the 1920s and 1930s and the 1960s.

In London, the Arts Council ended the decade with a major retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Arts but he didn’t live to see it, having passed away the year before. His trip to Britain in 1967 had renewed his fondness for the country. He had enjoyed visiting pubs and wandering the streets of Hampstead and Bloomsbury he had known so well during his stay in the country. (He had lived in Hampstead.)

Were he alive to visit now, it is unlikely he would believe the shift in racist rhetoric from the margins to the mainstream of British politics, nor the return of right-wing governments across the world. For the first time in many years his work feels pertinent to the modern day again.

Hyatt certainly believes so: “The issues dealt with by Heartfield in his prints are live issues in the UK and across the world: fake news; whitewashing of histories; racism; intolerance of difference and the weaponisation of fear. My favourite print is of an, always small, Hitler saluting and a background faceless funder in a suit placing wads of cash into his backward flexing hand. Heartfield subverts the gesture and changes its meaning in one graceful juxtaposition.

“This show should be seen by anyone who cares about the future of our children and our freedoms, because Heartfield made it and risked his life to do so. This show is titled Heartfield: One Man’s War but the war was fought by many heroes of all classes, shades and genders and their memory and heroism, shining from this exhibition, should inspire us all.”

Heartfield: One Man’s War runs at Four Corners, 121 Roman Road, London E2 until February 1. Admission is free