For both Brahms and the Beatles, Hamburg provided a hothouse to develop their talent and character, says SOPHIA DEBOICK.

“I cling to my native city as to a mother” wrote Johannes Brahms in 1862. The devastating emotion of his German Requiem, inspired by his mother’s death three years later, proved this comparison was no small statement. Hamburg made Brahms, the man, even if Vienna made his career. Hamburg – a gateway to Germany and beyond as the principle port of the Elbe, which snakes from the North Sea 600 miles into the continent’s interior – also has connections to Baroque composer Georg Philipp Telemann, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, son of Johann Sebastian, and Gustav Mahler, while opera composer Johann Adolf Hasse and siblings Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn were born in the city. Yet it was Brahms who felt his connection most strongly.

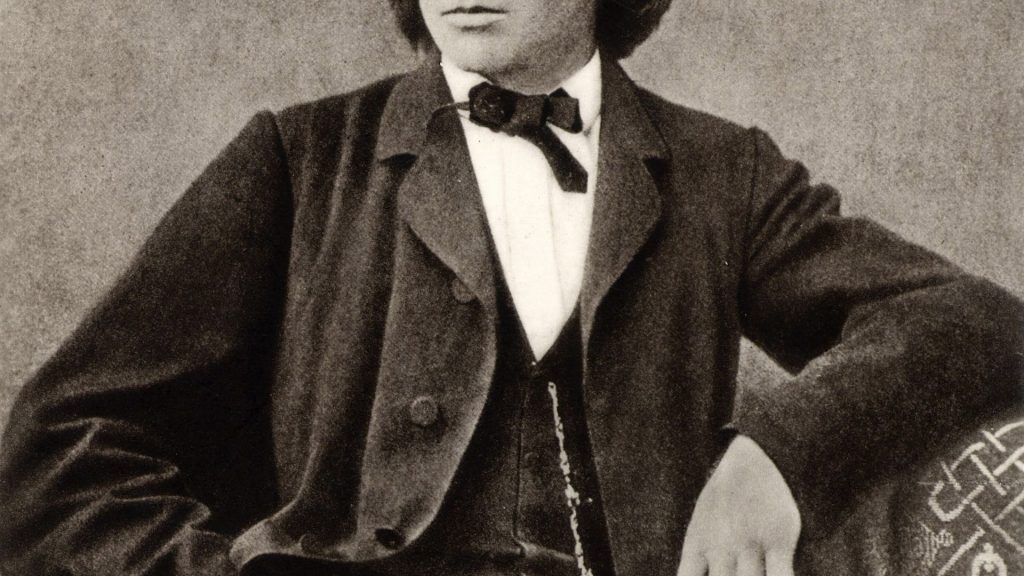

Born in May 1833 in the teetering timbered tenements of the Gängeviertel area, Brahms’ pedigree was not illustrious. His father Jakob was a jobbing musician, playing the French horn and double bass in the hotspots of the city’s St Pauli area, still home to its nightclubs and red-light district today. The story goes that Jakob was perennially short of money and did not hesitate to rope the 14-year-old Brahms into playing the piano in the city’s waterfront brothels to supplement the family income.

But this period also coincided with the young Brahms’ training under Eduard Marxsen, who drilled him in Bach, Mozart and Haydn, Beethoven and Schubert. He made his first public recitals in the city and composed prolifically. Although he later burned his very early compositions, his bombastic Scherzo in E flat minor and dramatic song Heimkehr, written the summer after he turned 18, survived.

Throughout his twenties, Brahms struggled to make it in Hamburg and at nearly 30 he was still living in the family home. He directed a women’s chorus, resulting in his setting for Ave Maria, and while the March 1859 Hamburg premiere of his Piano Concerto No. 1 went well, when it had debuted in Hannover with Brahms as soloist he was almost hissed off the stage.

But Brahms’ twenties were also when the indelible marks of his youth in Hamburg were seen in both his professional and personal life. His major early intervention in the War of the Romantics, the 1860 open letter he contributed to which attacked the “so-called Music of the Future” of the New German School of Liszt and Wagner, was informed by an impulse to musical conservatism rooted in his training under Marxsen.

But it was in Brahms’ relationships with women, it has been argued, that his boyhood experiences loomed largest. Brahms fell immediately in love with Clara Schumann after meeting her and her husband, critic and composer Robert Schumann – Brahms’ great champion – in Düsseldorf in 1853. He dedicated his 1854 Variations on a Theme of Schumann to Clara and wrote to her in 1855: “I can do nothing but think of you… Can’t you remove the spell you have cast over me?” He rushed to her side when Robert died in an insane asylum in 1856 and the pair were finally free to kindle their latent romance.

Very soon after, however, Brahms rejected Clara and went directly back to Hamburg. Biographers have claimed that he had a traumatic early initiation into sex in the Hamburg brothels where he played piano, embedding life-long sexual neuroses and a misogyny that puts one type of woman on a pedestal while regularly degrading others. He could never have countenanced a physical relationship with a woman like Clara – he once referred to the mother of seven as “Virginal as ever” – but was a prolific patron of prostitutes.

It has been suggested Brahms deliberately exaggerated the poverty of his childhood, his father more pecunious and respectable than he made out and his dockside piano-playing taking place in perfectly respectable inns. The story of psychosexual trauma may have been a convenient cover for unattractive impulses. Either way, his Hamburg boyhood loomed large in Brahms’ adult imagination. Even at the very end of his career, when he was finally offered the position of conductor of the Hamburg Philharmonic which he had been passed over for in 1862, prompting his move to Vienna, he rejected it wistfully: “It was long before I got used to the idea of going along other paths.” His romantic life too had been one of derailment of natural trajectories.

Over a century after a teenage Brahms played at the waterside haunts of St Pauli, a group of young musicians from further afield earned a crust in Hamburg’s night spots before going on to worldwide fame. The Beatles arrived in Hamburg in the summer of 1960 as relative novices but left with a technical ability and sense of how to work a crowd learned from night upon night of four-hour sets, as well as a new, worldly-wise perspective on life.

The Beatles were still the five piece that included Pete Best and Stuart Sutcliffe when they were booked by local entrepreneur Bruno Koschmider to play his Indra and Kaiserkeller clubs on Grosse Freiheit, off the Reeperbahn main strip of the red-light district, in 1960. While they were each paid 30 Deutsche Marks a week, far more than they could make in run-down Liverpool, the hours were punishing and they had to put up with sleeping in the dingy store room behind the screen of the Bambi cinema across the road.

When the band got an offer of even better money and, crucially, better digs from the nearby Top Ten Club, they broke their contract with Koschmider, who contrived to have them deported. But this was not before they had met Ringo Starr, who was playing the club as a member of Rory Storm and The Hurricanes, and had posed for a series of iconic photos taken by Sutcliffe’s girlfriend Astrid Kirchherr at the Hamburger Dom fairground.

But the Beatles were back playing the Top Ten the following March, although they were soon to become a different band. Stuart Sutcliffe left to enrol at the Hamburg College of Art, leaving Paul McCartney on bass duties. He would buy his famous left-handed Höfner violin bass at the Steinway shop, today Musik Rotthoff, in St Pauli, in response, and it would become a key part of the band’s image. The band kitting themselves out in top to toe leather also marked a new, albeit transient, stage in their sartorial innovations. Their first commercial release – backing Tony Sheridan on My Bonnie, where they were credited as ‘the Beat Brothers’ – was recorded in the city that June.

The band’s final turning point was in 1962. A run at the newly opened Star Club on Grosse Freiheit in April began with them learning of Sutcliffe’s sudden death from a brain haemorrhage, and their relationship with the city had changed. John Lennon later said of their return visits in November and December “We hated going back to Hamburg those last two times. We’d had that scene.” Ringo Starr had already replaced Pete Best, Love Me Do was creeping up the charts at home, and world domination was just around the corner.

George Harrison later confirmed “Hamburg was really like our apprenticeship, learning how to play in front of people”, but it was also the band’s first taste of adult life in a place, in Harrison’s words “full of transvestites and prostitutes and gangsters”, where drugs, money and sex were all freely available. For the Beatles, just as it had been for Brahms, Hamburg – then a city of vice and culture in equal measure – was a place of both artistic and personal self-discovery. As John Lennon later put it, “I was born in Liverpool, but I grew up in Hamburg”.