Rather than rub our noses in it, the French should remember their own era-defining national crisis and cut us some slack, says Allis Moss.

For a number of reasons France, in particular, has been playing hardball with the British over Brexit.

It doesn’t want to import Britain’s political crisis at a time when the gilets jaunes are already presenting enough of a handful. There are also some perceived advantages for the country from Britain’s exit from the EU – five more seats in the European parliament, businesses relocating across the Channel and more investment in Paris now than London.

But France – and Emmanuel Macron, specifically – should cut Britain some slack. Not only because any Brexit would, in fact, boost exponentially the right wing he deplores, but also because the French should empathise with Britain’s Brexit crisis. They don’t need to go back too far in their national history to find a chapter very similar to our own current predicament, when the country was in the grip of an identity crisis that asked fundamental questions about the state’s own future.

This episode is beyond living memory but still deeply embedded in the French national consciousness. It was a drama so divisive and seemingly insoluble that the scholar Theodore Zeldin called the two camps “deux Frances”.

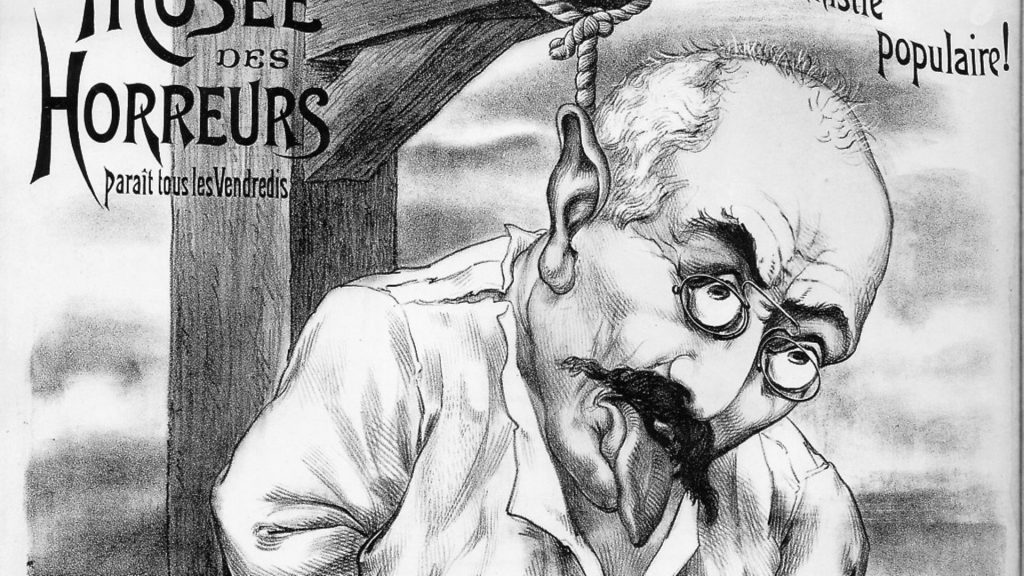

France is no stranger to upheaval. Revolution, restoration, empire, war and occupation have all taken their turn in the last two centuries, but Zeldin wasn’t referring to any of these. He was talking about the Dreyfus Affair, the last in a series of deeply damaging political scandals that rocked the infant Third Republic on the eve of the 20th century.

The row began in a closed military court at the height of the Belle Époque in a city that saw itself as the centre of the civilized world. Paris had just raised its controversial Eiffel Tower to the skies and was preparing to show itself off as the forefront of innovation in its 1900 Exhibition.

But modernisation was itself part of the collision between reactionary and progressive politics and the pursuit of rival visions for the country’s future. New technology also played a part with the mass press driving the narrative further and faster, as social media has ours.

Ostensibly about the fate of one man framed for spying, the struggle was really about the fate of France. The young, Jewish Captain Alfred Dreyfus merely had a walk-on part in his own ‘affair’. The real battle, near bloodless but lasting years, was for the survival of the Third Republic.

The Republic had limped home in the blood and dust of the Paris Commune uprising, becoming a kind of haphazard default when all else failed. Some in France hankered for the return of a king but could not agree who, others had a soft spot for an emperor, a charismatic military strongman who would restore honour and pride lost in the humiliating defeat of the recent ill-advised war with Prussia.

Those opposing any kind of absolutism were wedded to the Republic – but what kind? An innocent man left to rot on Devil’s Island off distant French Guiana, even after the real culprit was revealed, became an inadvertent standard-bearer for a debate about what kind of country people wanted to live in.

The country’s leadership faced a stark choice. Expose the corruption and overturn the rigged ruling of the court or maintain appearances and military honour at all costs. This did not satisfy those for whom the Republic stood for all the Revolution of 1789 had achieved – Liberté! Égalité! Fraternité! – and the Rights of Man and the Citizen! By these tenets, everyone should have the right to a fair trial, and for Dreyfus’ supporters, one man’s injustice was a stain on the entire nation.

Long before Macron named his new party La République En Marche! – and perhaps it was no coincidence – the rallying cry to the whole of France from the novelist Emile Zola, Dreyfus’ most celebrated champion, was “La vérité est en marche et rien ne l’arrêtera”.

Truth was on the move and nothing would stop it. Zola’s appeal was for a modern state, founded on enlightenment principles. Defiant when his newspaper columns in Le Figaro were axed after its subscriptions fell, Zola published them as pamphlets, writing: “Let it drag its weary course a few weeks longer, try to stifle the truth, refuse to do justice, and you will see whether you do make us the laughing-stock of all Europe…”

A week later, Zola dropped his bombshell and put the tinder to the flame in “J’Accuse…!”. The incendiary open letter, published as a front page splash in a daily paper sympathetic to the cause, attacked officialdom from the president down, shocking the nation.

The feud echoed from the cabaret theatres and cafés of avant-garde Montmartre through university halls and academies to parliament itself. It polarised opinion, breaking friendships and forging new alliances. A drawing by the anti-Dreyfusard cartoonist, Caran D’Ache, shows a squabbling family who tried and failed to avoid mentioning the wretched subject.

Even the Impressionist painters were swept into the fray with Monet and Pissarro siding with Dreyfus, and Degas against – his lifelong friendship with the librettist Ludovic Halévy falling by the wayside as a result.

The campaign of Zola and his allies was to draw in the great socialist leader Jean Jaurès, writer and Academician Anatole France, and the Catholic poet Charles Péguy. Many young, upcoming writers and artists, often with less to lose, answered the call, among them the Swiss painter, Félix Vallotton. A Parisian gallery owner re-papered his entire interior with copies of “J’Accuse…!” Mockingly dubbed ‘the Intellectuals’, the nickname was to stick as a badge of honour.

Then, as in Britain now, the language of debate in public life coarsened and became emotive. Violent metaphors and derogatory new word formations appeared like those from the Brexit lexicon. Just as rabble-rousers in Britain dish out propaganda and bile, so fin-de-siècle demagogues peddled misinformation, stoking fears of plots from within and conspiracies without.

Like our own public figures, Zola – himself half-Venetian so the target of jibes about what it meant to be French – received threats, slurs and constant ridicule in the press. He would live to see Dreyfus pardoned but not exonerated and rehabilitated back into the army with full, if somewhat hollow, military honours. Less than a decade later Jaurès would be assassinated, shot in the back in a Parisian tea shop, for trying to stop the looming First World War.

Conflict was an inherent part of the Affair; from suspicions that those with ancestral roots elsewhere might be ‘spies’ to fears about the restructuring of power on the continent after the Prussian War led to the creation of the new German empire.

As Christopher Clark argues so convincingly in The Sleepwalkers, loss of territory from France from that war with Prussia was to help pave the way for the Great War, a war of revenge, that itself sowed the seeds for the next. It may be an unwieldy point to make but it is never not worth making, that France – and Britain – should remember their joint history in the conflicts of the 20th century when they bicker about extensions and the facilitating of Brexit, because of such flimsy excuses that we are supposedly bored, or tired or worried about doing business as normal.

Admirers of the German thinker Leopold von Ranke might insist that every part of history is unique. Yet similarities mean we have the chance to learn from the past. Of all the parallels between Britain’s Brexit ordeal and the challenges Zola, Jaurès and their supporters confronted arguably the most compelling are the surge in nationalism, the preference for nostalgia and questions about multicultural societies and migration.

As we face these tests again, some in France including Macron might be afraid the Brexit impasse will never be overcome. Like all bad things, it must. And while we grope and stumble our way towards a solution, centrists, progressives and liberals across Europe should support one other.

In this spirit of understanding, which includes time and space for the UK to extricate its divided self from disaster, France might recall that when two visions of the future collided in the Third Republic, it took years for the progressives to win.

The Republic that Zola and Jaurès fought for went on to endure the longest of any French republic to date. Yet the clash between reactionary and liberal politics cast a long shadow. Nationalism and the right remain a potent force in France and beyond in Europe – and the current French president should bear in mind that any form of Brexit will help it.

– Allis Moss is a freelance journalist and broadcaster and a White Rose Scholar in European history for Leeds University.