A striking feature of the Brexit camp’s narrative in the UK both before and after the 2016 referendum has been the repeated claim that leaving the EU is consistent with the lessons of history.

Such ‘lessons’ are popularly believed in the UK, but they fail to stand up to close examination.

First, there is the question of the UK’s geography. Advocates of Brexit echo a point made frequently by former French president, Charles de Gaulle, the UK is physically separated from continental Europe and is an island state that looks to America as much as it does Europe.

Britain is, of course, an island state but one that has been physically linked to France through the Channel Tunnel since 1994. Moreover, Britain is an island state with European neighbours.

Second, and not unrelated, it is claimed that Britain’s identity is global rather than European. Nostalgic memories of the British empire loom large here.

There is a clear longing in the speeches of prominent Brexiteers like former foreign secretary, Boris Johnson, and Liam Fox, the international trade secretary, to rekindle and deepen trade ties with Commonwealth nations to seamlessly replace those that it currently has with the EU.

But there is little evidence that the 51 Commonwealth countries are eager to rally round the UK and forge new ties with London. For many of these countries the priority remains strengthening relations with the EU, the world’s second largest economy, and consolidating their own regional ties.

States like Canada are keen to protect the North American Free Trade Agreement; Australia and New Zealand are closely linked to the dynamic Asia-Pacific region; and the large, rapidly growing Indian economy finds limited attraction to a country with the market size of Britain.

While in Britain may feel nostalgic looking back to empire, many former colonies don’t share such happy memories.

Third, the Brexit camp has repeatedly emphasized that Britain’s experience during the Second World War made the country – in both in its fundamental nature and in its national interests – different from, and purportedly superior to, other EU member states.

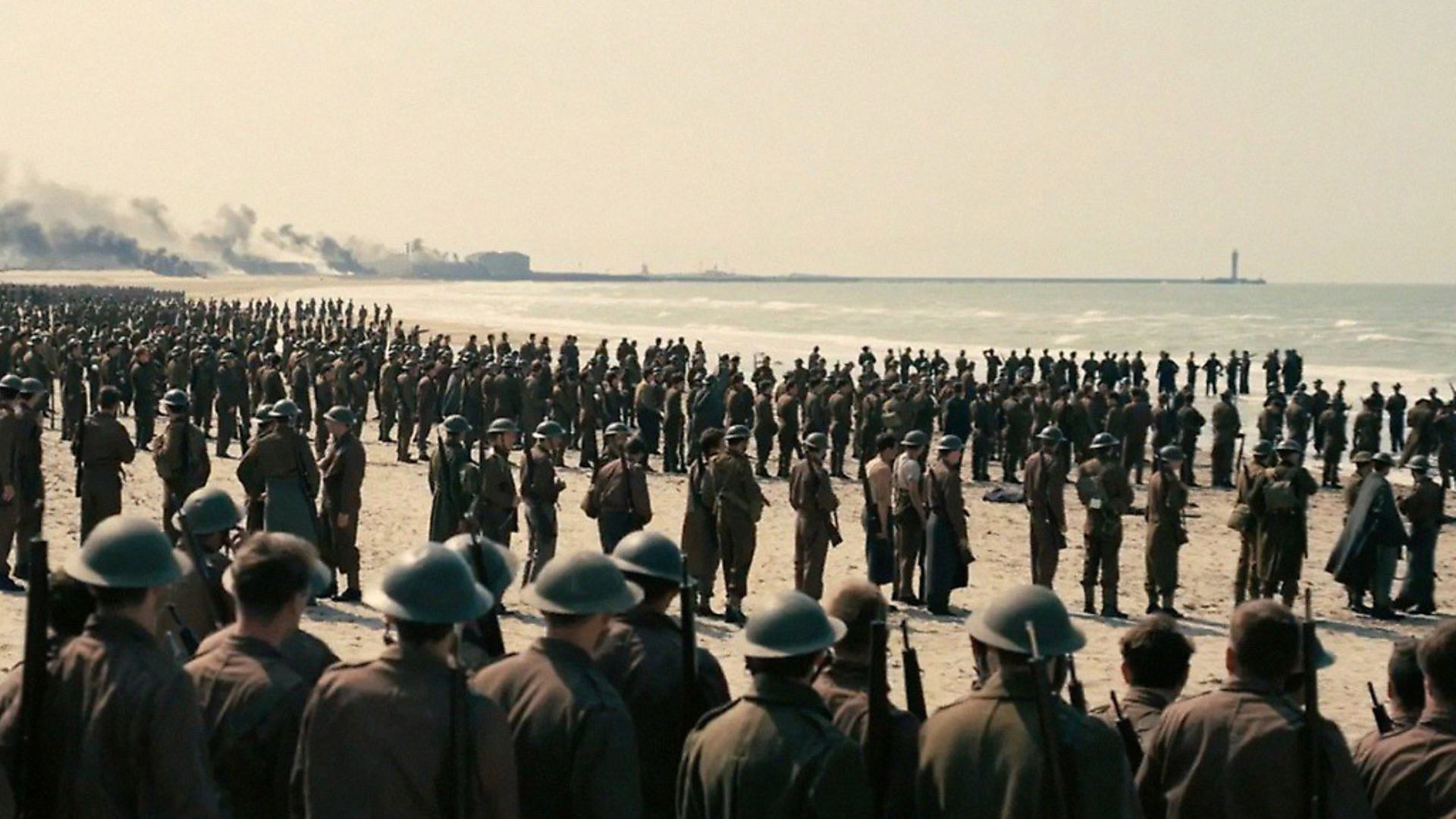

A strong sense of British exceptionalism centres on the idea that Britain stood alone against Nazi Germany between 1939 and 1941 and relied on its ‘Dunkirk spirit’ to determinedly resist Hitler until it was eventually joined in this endeavour by the Soviet Union and the United States.

Popular films like Dunkirk and Darkest Hour continue to project the UK as valiant and heroic during that two-year period.

For supporters of Brexit, the essential lesson to be derived from this aspect of history is that the May government has nothing to fear from standing alone in its exit negotiations with the EU and if necessary it can simply leave without a deal.

But this account of Britain’s wartime performance is highly selective. By the late 1930s, the British government was linking its own fate to that of Europe. In 1939, the British declared war on Nazi Germany – not because it was attacked by Hitler’s regime – but because the Nazis (and the Soviets) attacked Poland.

It should also be noted that Britain, by choosing to fight on against the Nazis after 1939 clearly demonstrated it was not prepared to abandon the other European nations under Nazi occupation.

Indeed, Winston Churchill recognised in 1940, Britain as a European state could never withdraw into some sort of island sanctuary and be indifferent to the fate of the European continent.

Fourth, the Leave side has argued that Brexit is fully consistent with the foreign policy vision of Churchill, a victorious wartime leader widely credited with playing a key role in defending liberal democracy against the spread of fascism.

Churchill’s observation – prior to the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) – in September 1946 that ‘we are with Europe, but not of it’ has been repeatedly cited by the Leave camp as validation of their stance toward the EU.

Meanwhile, Boris Johnson, a key figure among the Brexiters and biographer of Churchill, likes to assume the Churchill mantle by warning frequently about a new form of menace on the continent – the establishment of ‘a European superstate’ spearheaded by Germany.

At the same time, the Leave side likes to point to Churchill’s special relationship with the United States during the Second World War as a reason why it is not in Britain’s interests to remain in the EU.

But the use of the Churchill analogy to support the Brexit case is thoroughly misleading. It was Churchill who advocated a ‘United States of Europe’ in 1946, and while concerns over a rapidly declining British empire during the post-war period initially limited Churchill’s commitment to the European continent, the former prime minister had publicly and enthusiastically endorsed the first British application to join the EEC in 1961.

Nor is there any evidence that Churchill saw British membership of what was then called the EEC as an impediment to UK-US relations.

All British prime ministers since the UK’s entry into the EC in 1973 have continued to place considerable emphasis on the special relationship with Washington.

Indeed, it was an American president, Barack Obama, who observed before the EU referendum that outside the EU the UK would be less valuable to other countries and less able to fight for its own interests.

In other words, the UK outside the EU is less valuable to the US than a UK within the EU.

The Trump administration has repudiated that view, but has made it clear any free trade agreement with a post-Brexit UK must be consistent with ‘America First’ principles.

Yet if the Brexiters’ reading of history has been flawed, why has the Theresa May government championed the Brexit cause on that basis?

The answer is that May, like her predecessor, David Cameron, has generally failed to distinguish between concerns about internal Conservative Party unity and wider considerations of British national interest, and has shown little political interest in challenging the inaccurate historical claims of the Brexiters.

May’s complicity has been aided and abetted by jingoistic and fervently pro-Brexit large circulation media outlets like the Telegraph, Daily Mail, Daily Express and Sun and the pro-Brexit stance of Jeremy Corbyn.

Ultimately, a pro-Brexit consensus amongst the two main political leaders has contributed to a climate in which the re-writing of history in the UK has occurred all too often with alarming ease.

Robert G. Patman is a professor of international relations at the University of Otago, New Zealand