PETER TRUDGILL finds much in common between European languages and the English spoken by African Americans.

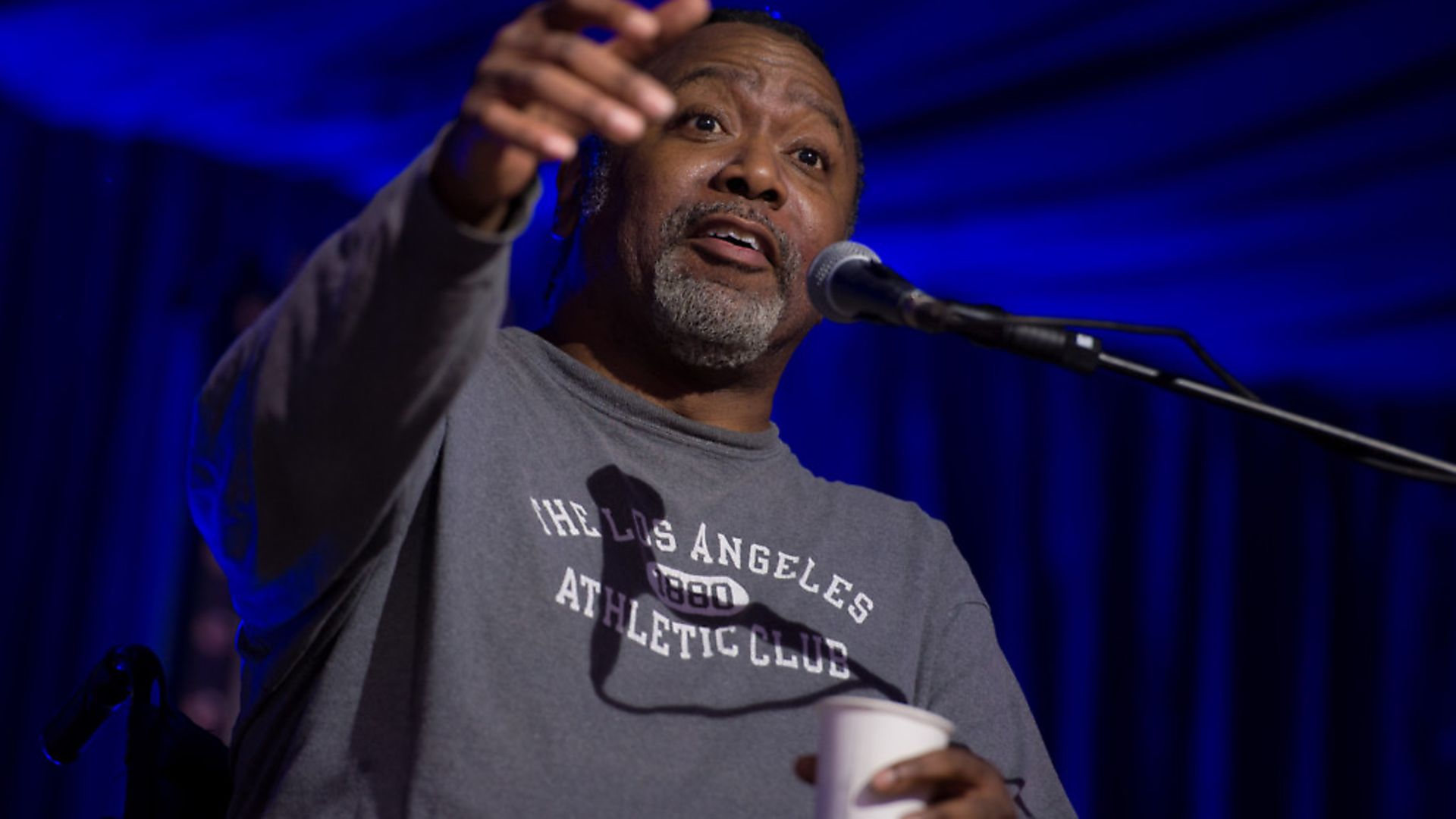

One of the African American comedian Reginald D. Hunter’s best jokes comes from a television appearance here in Britain. It was a linguistic gag. Hunter related a story that went something like this:

He was in a bar, somewhere in the UK, talking to a local woman. When she found out that he was a comedian, she asked if he had ever heard of Tommy Cooper.

‘He dead!’ Hunter replied.

‘I must correct your grammar,’ the woman said, ‘it’s ‘he died’.’

‘Yes’, responded Hunter, ‘first he died. Now he dead.’

There are, unfortunately, still misguided people in our country who think it is perfectly acceptable behaviour to go around ‘correcting’ other people’s grammar. They indulge in the arrogance of believing that the grammar of their own dialect is correct, and that the way everyone else speaks is wrong.

Hunter’s grammar is certainly different from mine. But it is perfectly correct – and also extremely interesting. Like millions of other black Americans, Hunter is a speaker of the variety of our shared language which linguistic scientists call African American Vernacular English (AAVE).

This type of English is in some ways very different from the dialects spoken by most white people in the United States. And there is, sadly, a long history in the USA of this dialect, totally unjustifiably, being looked down upon and discriminated against. This is, of course, all part and parcel of the way in which African Americans have been oppressed generally in the United States.

The fact is, however, that Hunter’s dialect of English is a perfectly normal variety of language, with its own rule-governed grammatical structures. One such is illustrated by the sentence ‘He dead’. In constructions such as ‘She busy’ and ‘He my father’, AAVE has no verb ‘to be’ – in technical terminology, we say there is no copula. It is quite easy to see that the verb ‘to be’ here is totally unnecessary, as the meaning is entirely clear without it.

Many other languages around the world, including some in Europe, also have this same, very sensible construction without a copula. In Russian, on mertv is literally ‘he dead’, and Moskva gorod ‘Moscow city’ means ‘Moscow is a city’. Turkish has the same zero copula structure: o öldü, ‘he dead’. Other European languages can also behave in the same way: Maltese John tabib, literally ‘John doctor’, gets translated as ‘John is a doctor’, as does Hungarian John orvos. So AAVE has a grammatical structure which is distinctive in the context of the English language but is perfectly normal in the context of the languages of the world.

Interestingly, AAVE also has the ability to make a grammatical distinction involving the copula which is not available in most other English dialects, including Standard English. There is an important difference of meaning in AAVE between she busy, and she be busy. You can say she busy right now, but it would not be grammatical to say usually she busy – you would have to say usually she be busy.

The point is that forms with be refer to events which are repeated or occur habitually (she be busy every weekend) – it is often called ‘habitual be’ – while forms with no copula refer to non-habitual or single events or situations. In AAVE one can’t say she be my mother, because that would imply that she was only your mother from time to time; the correct form is she my mother.

This grammatical distinction between non-habitual and habitual events is also expressed grammatically in many other languages round the world. In Spanish, ‘she is busy’ is ella está ocupada, while ‘she is my mother’ is ella es mi madre. The distinction between está and es, two different ways of expressing ‘is’ in Spanish, is very similar to the grammatical distinction between be and no copula which is found in the kind of English spoken by Reginald D. Hunter.