SOPHIA DEBOICK on the Minnesotan city and its most famous musical son.

Minneapolis has always taken its own path. When Bob Dylan arrived in the city in 1959 from Duluth, 150 miles further north, he discovered that Minneapolis – the ‘City of Lakes’ – and its twin city Saint Paul were “rock and roll towns” in the grip of a fever of “surfing rockabilly – all of it cranked up to ten with a lot of reverb”.

Four years later, after making his first career moves in Minneapolis and then going to New York, Dylan’s second album announced him as a remarkable singer-songwriter and that same year Minneapolis surf rock outfit The Trashmen had a hit with the madcap Surfin’ Bird.

Minneapolis thus proved itself able to deliver both musical heavyweights and brilliant ephemeral pop. It was a pattern that would be repeated in the coming decades.

Dylan’s connections to Minneapolis were many.

He had lived above a drug store at 327 14th Avenue SE, performed at beatnik hangout The Scholar coffee bar, recorded part of Blood on the Tracks (1974) at the city’s legendary Sound 80 recording studio, and for 10 years was a co-owner of the historic Orpheum Theatre on Hennepin Avenue.

But Dylan was not a Minneapolis native and only one all-time icon is truly synonymous with the city.

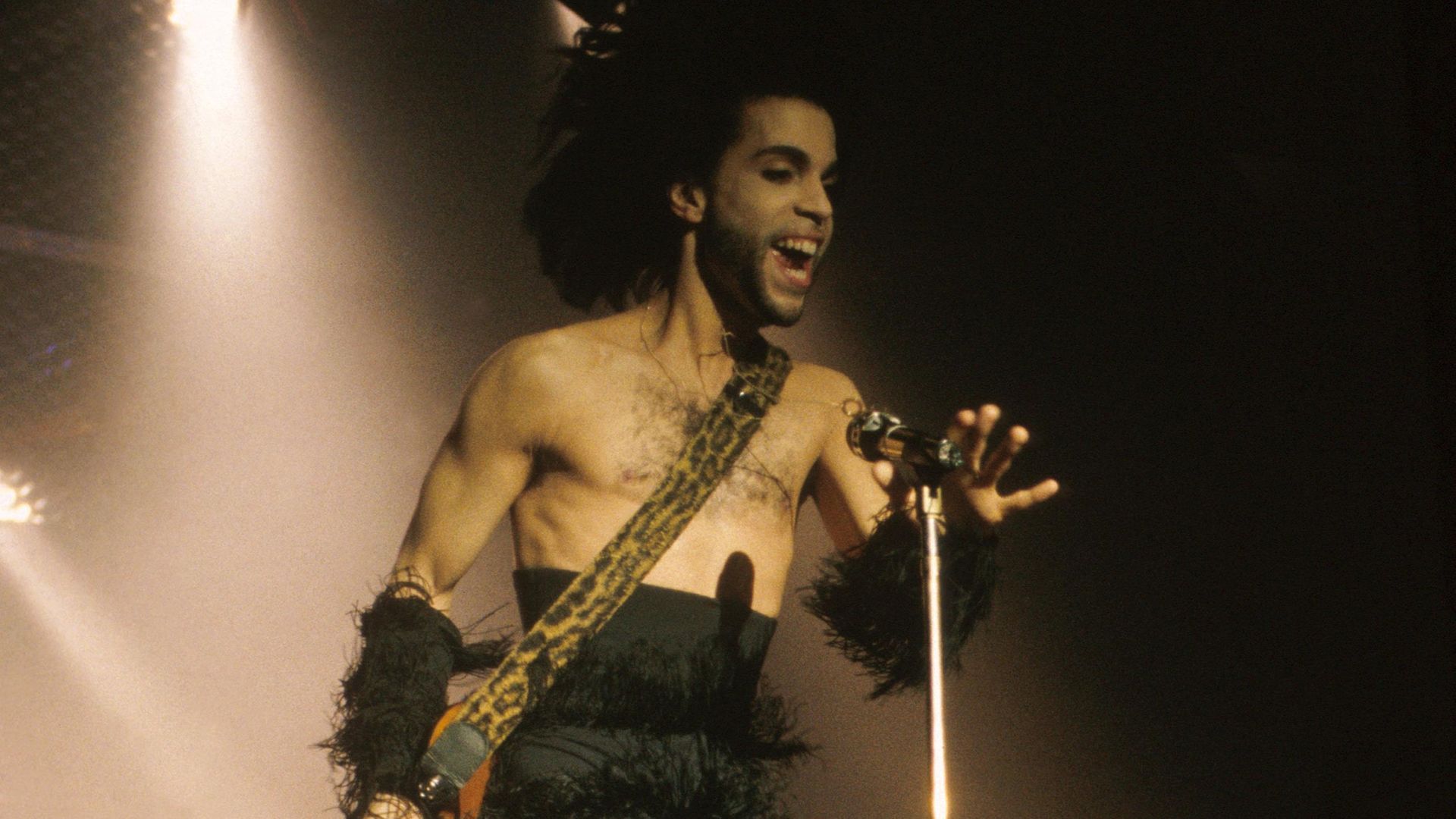

Born in Minneapolis’ Mount Sinai Hospital in 1958, Prince Rogers Nelson was the son of musicians and had both the city and music in his blood.

Growing up in Minneapolis’ Northside neighbourhood in poverty, the diminutive, epileptic young man was an unlikely star, but his prodigious musical talent saw him become the lodestar of Minneapolis music in the 1980s.

An auteur and master musician who often played every instrument on his albums, his ‘Minneapolis sound’ changed the course of pop, bringing together rock guitars, synths and highly processed drums into a new, hybrid version of funk.

But for all his world-changing energy, Prince was always intimately connected with the city of his birth.

Uptown from 1980’s Dirty Mind – the album on which he unveiled his signature sound and more-than-risqué lyrics – was a celebration of Minneapolis’ multi-racial, artistic district.

Feature film vehicle Purple Rain (1984) was filmed in Minneapolis and featured both its iconic First Avenue music venue as well as some of Prince’s many side projects – The Time, Morris Day, Apollonia 6, and Wendy and Lisa.

On 1985’s follow-up to the Purple Rain LP, Around the World in a Day, Prince sang of an imagined utopia called Paisley Park, where “colourful people” smile with “profound inner peace”.

Within two years, he had built that utopia, a $10 million recording studio in Chanhassen, 20 miles south west of the city centre which later became his home. He once said “I will always live in Minneapolis.

It’s so cold, it keeps the bad people out”, and in 1995 he responded to Lenny Kravitz’s single Rock and Roll Is Dead with Rock ‘N’ Roll Is Alive! (And It Lives In Minneapolis). When Prince died at Paisley Park in 2016, an integral part of Minneapolis’ identity died too.

Just as Prince was breaking through with his first hit, I Wanna Be Your Lover, in 1979, another sound was fast emerging in Minneapolis.

Twin/Tone records had made its maiden release in 1978 with an EP by local punk legends The Suburbs, regulars at alternative scene venues like 14 South Fifth Street’s Jay’s Longhorns Bar and First Avenue.

But into the 1980s Twin/Tone would churn out perfect college rock, with the Replacements as the label’s centrepiece.

Starting as a classic rock-influenced outfit, delightfully named Dogbreath, the Replacements soon heard the siren call of punk from Britain.

1980’s Shiftless When Idle captured their snotty-nosed adolescent urgency, but they soon segued into a more sophisticated new wave sound.

They were also a band deeply invested in Minneapolis’ local mythology.

While the pure punk of Raised in the City (1981) included a mention of that common excursion outside Minneapolis, a “Cruise to the lake/ Fun, fun, fun”, 1983’s laidback Buck Hill referenced a skiing area to the south.

But the affectingly wistful Skyway (1987) was the Replacements’ ultimate Minneapolis song, where the city’s unique system of pedestrian bridges – nine miles of pathways which connect 80 blocks of the city – was used as a metaphor for an object of love who is out of reach.

Despite signing to Seymour Stein’s Sire Records, the band’s excesses overshadowed the quality of their music, their drunken gigs attended as spectacle, and they are remembered as one of rock’s greatest nearly-rans.

Yet, as part of Minneapolis’ alternative rock scene, which also included Twin/Tone acts Soul Asylum and Babes in Toyland, and the Replacements’ arch rivals, Bob Mould’s Hüsker Dü, the Replacements had been precursors to the sounds that would explode out of Seattle in the early 1990s.

Minneapolis’ alternative scene was hardly wholly discrete from its global pop success though. Steven Greenberg was a producer for Twin/Tone when he wrote one of the biggest hits to ever come out of Minneapolis.

Funkytown was the sometime mobile DJ’s own attempt at a disco track, but incorporated his love of the nascent synthpop of Kraftwerk to make a track that bridged past and future.

He recorded the track at Studio 80 with vocalist Cynthia Johnson, and they punningly called themselves Lipps Inc.

The song was irresistibly funky and became an international smash hit, spending two weeks at No.1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in June 1980.

Although Minneapolis was not the “Funkytown” of the title – the lyrics “Gotta make a move to a town that’s right for me/ Town to keep me movin’/ Keep me groovin’ with some energy” coming from Greenberg’s unfavourable comparison of the city with New York as well as the fellow Midwestern cities of Chicago and Detroit – Lipps Inc. was well-embedded in Minneapolis pop.

Cynthia Johnson had been the singer and saxophonist in Flyte Tyme, the project of James ‘Jimmy Jam’ Harris and Terry Lewis, a duo who had met at high school. That band then became The Time in 1981, but when Harris and Lewis were fired by Prince in 1983 they went on to become one of the most powerful writing and production duos of the 1980s and beyond.

After work on Alexander O’Neal’s eponymous debut and giving The Human League a stonking hit in Human (1986), Harris and Lewis became pivotal to Janet Jackson’s career for the next three decades, sharing writing and production credits with her on nine of her 10 US No.1s.

Songs like Nasty and What Have You Done for Me Lately from 1986’s Control and Escapade from Rhythm Nation (1989) were perfect examples of how Prince’s Minneapolis sound was adopted wholesale by other artists.

Harris and Lewis’ first signing to their Perspective label, Minneapolis gospel choir Sounds of Blackness, meanwhile – another project in which Cynthia Johnson was involved – resulted in the uplifting, Grammy-winning single Optimistic (1991), which they have said is their favourite song they’ve ever done. Work with Michael Jackson, Kanye West and seemingly everyone else in the music industry since has made them living legends.

“Growing up in Minneapolis,” Harris has said, “if you were a black band, there were a bunch of clubs you couldn’t play in Minneapolis because they just wouldn’t hire you to play.” Since the 1950s, and the birth of the Minneapolis sound generation, the city has seen huge demographic change – while some 98% of the city’s population was white then, that figure is now around 60%.

One of the biggest artists of 2019, Detroit-born Lizzo, who released the black pride anthem My Skin in 2015, cut her teeth on the Twin Cities hip hop scene.

But when George Floyd was killed outside the Cup Foods grocery store on Minneapolis’ Chicago Avenue earlier this year it was evidence that the discrimination Harris had suffered was hardly a thing of the past, and the response to his death has seen Minneapolis once again send shockwaves throughout the world.