Documentary-maker Michael Moore’s new film paints a disturbing picture of the US, by looking back at a 1980s book which predicted how the country could fall victim to a form of fascism. BENJAMIN IVRY reports

Amid civic chaos, people cling to books which seem to clarify murky times. The American documentarian Michael Moore’s latest film, Fahrenheit 11/9, promotes an academic study written a generation ago, to elucidate the current administration in the White House. On November 9, 2016, the day after the US presidential election, Moore sent his six million followers on Twitter a misquote from Bertram Gross’s Friendly Fascism: The New Face of Power in America (1980): ‘The next wave of fascism will come not with cattle cars and camps. It will come with a friendly face.’ Gross’s exact words were as follows: ‘The next wave of fascists will not come with cattle cars and concentration camps, but they’ll come with a smiley face and maybe a TV show… That’s how the 21st-century fascists will essentially take over.’

But beyond such semantic quibbles, was the Philadelphia-born Gross (1912-1997) a guru for our times?

A professor of public policy and planning at Hunter College at the City University of New York, Gross’s main achievement in American social and labour history was to write the Humphrey–Hawkins Full Employment Act (1978).

This law, in preparation since the later years of the Second World War, was aimed at making America a more compassionate society. A significant step in the fight against poverty, the bill was signed into law by president Jimmy Carter, to address rising US unemployment levels in the 1970s.

Yet Gross remains more famous, and in some circles notorious, for Friendly Fascism, a primal scream against what America would become in the era of Ronald Reagan. Gross asserted that the growth of big business and big government might lead to the danger of fascism in America.

He began writing his book before Reagan was actually elected president, yet the national mood was already established.

The smiley face was omnipresent, although only to some observers had Reagan already prompted recollection of a quote from Shakespeare’s Othello about how someone may ‘smile, and smile, and be a villain’. The ostensible benevolence of an alliance between business and government conglomerates could, Gross warned, appear kinder and gentler than traditional forms of fascism.

Gross writes of how democratic procedures and human rights will be manipulated by a radical right, funded by corporations using modern technology. This scenario does seem to foreshadow current events on the American political scene. Gross’s view of a new power elite that manipulates the public, sedated by television, is a less innovative critique, insofar as psychological control of the public by mass media is a time-honoured element of dystopian visions.

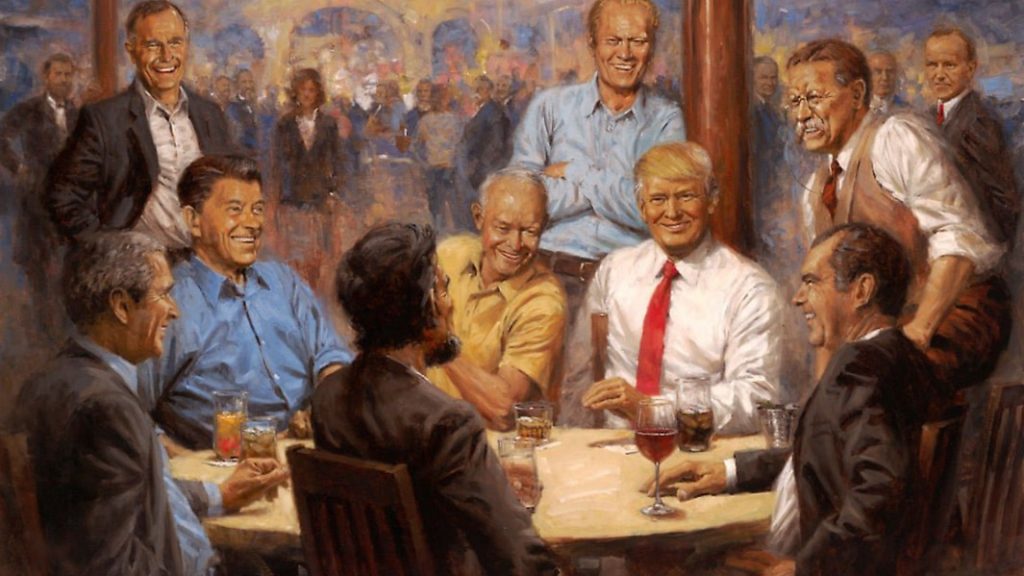

Because Gross mentioned television, it was natural that a generation later, some readers would take notice when a reality show personality decided to run for public office. In August 2015, Charles Henry, a professor emeritus in African American studies at the University of California, Berkeley, blogged about his concern at the new relevancy of Gross’s book with the candidacy of Donald Trump.

In March 2016, with the Trump campaign well under way, Friendly Fascism was reprinted in e-book form by Open Road Media. David Yamada, a professor of law at Suffolk University Law School, Boston, Massachusetts, blogged about the ‘terrifying clairvoyance of Bertram Gross’ with respect to the Republican Party’s platform in the upcoming national election. Professor Yamada noted: ‘Friendly Fascism eerily anticipated the descent of America into a state of plutocracy – an increasingly authoritarian society run by the wealthy and powerful for their own benefit.’

Yet the first reviewers of Friendly Fascism a quarter century earlier by no means greeted the book with unanimous praise. The political scientist Alan Wolfe, a professor at Boston College, offered objections to Gross’s predictions in a September 1981 review in Contemporary Sociology. Gross had posited that friendly fascism might occur without people noticing.

A kindly president, representing a corporate-government establishment, would rule the land. Wolfe pointed out that fascism is unfriendly in its ‘sheer terror and barbarity against the human spirit… Fascism is not the sort of thing that just happens. It is a counter-revolution requiring an act of will, the right preconditions, and a seizure of state power’.

From today’s perspective, we may note that no one, not even those who may have voted for him, would describe Donald J. Trump as kindly or friendly. Nor do Trump’s personal wars, noisily declared upon the US media, intelligence agencies, military organisations, and almost every element of the American governmental infrastructure, follow Gross’s narrative blueprint. So although some techniques of the current administration, such as promoting hatred of racial, ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities, are from the classic book of fascism, most others are not.

In his 1981 review, Wolfe went on to note: ‘Fascism, most writers argue, is strongly related to empire… Given this historical relationship, one might conclude that American fascism, even if friendly, would be somehow related to overseas expansion.’ On the contrary, today’s US imperial presidency has been adamantly moving towards isolationism, however impossible that prospect might be in reality.

Some observers of the present depressing ruins of American democracy may take hope in the fact that fascism requires overwhelming majority approval. Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 11/9 heavily juxtaposes Trump with the advent of Adolf Hitler in Germany. Yet when Hitler was elected, his popularity levels, as far as can be calculated retrospectively by historians about a time before such polling took place, was at least double that of Trump, who hovers around 40% approval. As their sufferings during the Second World War increased, the German population’s affection for Hitler would decline. Yet it may never have been as low as Americans felt about their new president from the very start of his administration.

Rather than trying to pinpoint elements of Gross’s book that apply to today’s US government, Moore might have more usefully looked to other American writings that make no pretence at factual prediction. The Nobel prizewinning American novelist Sinclair Lewis wrote It Can’t Happen Here (1935) about Berzelius ‘Buzz’ Windrip, a demagogue who runs for president, sputtering about patriotism and old-style American ways. Windrip is elected and opts for a totalitarian government bolstered by paramilitary support, akin to Hitler’s Schutzstaffel (SS). A journalist forms the main opposition to Windrip’s rule. Lewis’s fiction was reputedly drawn from the example of Huey Long, a corrupt Louisiana politician who was shot in 1935 while planning to run for the presidency. It covers more themes that echo with the Trumpian present than Bertram Gross’s factual study could.

Another novel which has been discussed as prescient in the current political climate of Washington, DC, is Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America (2004). In Roth’s imaginary tale, Charles Lindbergh, an anti-Semitic isolationist, defeats Franklin D. Roosevelt in the presidential election of 1940. While mainly concerned with the effect upon American Jews of an anti-Semitic regime that allies itself with European fascism, The Plot Against America joins other novels, from Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962) to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), that are seen as illuminating views of totalitarian or dystopian societies. These novelistic fantasies share with theoretical predictions by political scientists a lack of direct effect upon the American electorate or the regime in place.

While writers of fiction have no obligation to include optimistic messages in their depictions of a future ruined America, nonfiction writers, Gross included, often want to leave readers with something apart from sheer despair. So Gross mentioned that collective political activism remains a useful instrument against any creeping advance of fascist ideology. Whether or not this suggestion appears convincing is a matter of personal taste and conviction.

While mulling over the correspondences, and major discords, between predictions by Gross and other writers as they pertain to the current situation in America, we may recall the way that fascist rulers treat writers. Pre-empting or co-opting their works for political purposes, everything written in a fascist regime becomes the property of the state. In an oddly comparable way, Michael Moore co-opted the title of the American author Ray Bradbury’s dystopian novel, Fahrenheit 451, over Bradbury’s repeated objections, for his 2004 documentary film Fahrenheit 9/11. Bradbury died in 2012, and six years later, Moore has again overridden the author’s express wishes by using the title of Bradbury’s novel in his latest film. While neither an expression of fascism or even friendly fascism, Moore’s persistent disrespect for a gifted American writer gives one pause about the seriousness of his film projects.