Much has been pinned on the 16th-century seafarer, but was one of England’s national heroes a patriot or a pirate? HORATIO MORPURGO offers a fresh perspective.

The air was ‘very cool and pleasant, by reason of those goodly and high trees that grow there so thick’. In February 1573 a party of armed men were cutting their way through rainforest above Panama. Four Africans went ahead, clearing a path for the main party, made up of 18 Englishmen and 26 other Africans, or ‘Cimaroons’ more accurately.

These were escaped slaves who had built a new life in the mountains. Their unrivalled knowledge of the terrain and hostility toward the Spanish made them ideal allies for Francis Drake, who was looking to ambush the ‘treasure train’ – the mules by which gold and silver were transported across the Isthmus.

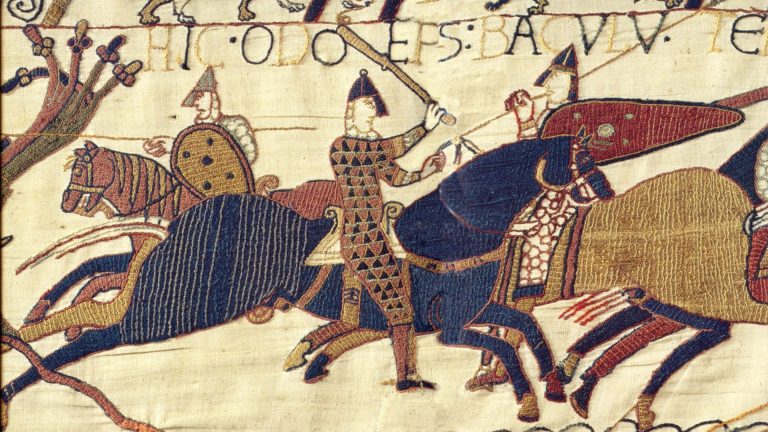

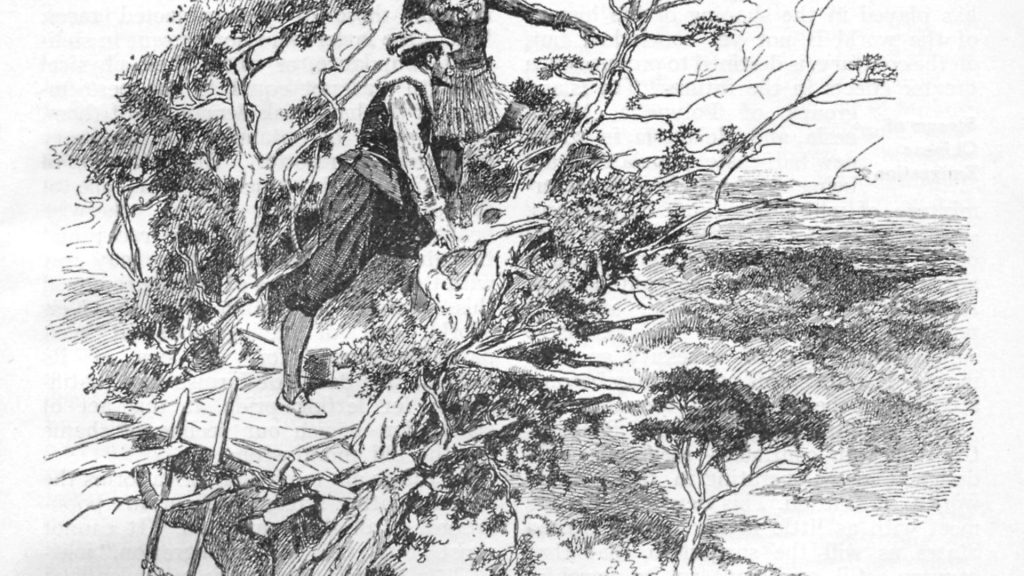

On ‘a ridge between the two seas’, the Africans showed their English guests ‘a great tree’ into which steps had been cut. Its crown formed ‘a convenient bower, wherein ten or 12 men might easily sit’. Drake was taken up first and sat in it with the Cimaroon leader. Looking over for the first time into the Pacific Ocean, he ‘besought Almighty God of His goodness to give him life and leave to sail an English ship in that sea’.

The account of this expedition, to which Drake wrote a preface, describes the Cimaroons as ‘no less valiant than industrious’ and praises their way of life at every opportunity. When he sailed home the following year, with a hold full of Spanish treasure, also on board was one ‘Diego’, a Cimaroon who insisted on going with them. He later sailed with Drake on his circumnavigation, as a Spanish interpreter, on the same terms and for the same pay as European crew.

And yet it is quite true that Drake had, just five years earlier, completed the second of the two slaving voyages in which he participated. Both were commercial failures but that is hardly the point. Which was he? Ruthless trafficker in human lives? Or forger of bold alliances and, apparently, friendships across the race divide?

The historical record does not explain this contradiction. There is just a gap. Where the explanation should be, there is a paradox instead. Later legendary accretions around his name – whether they made of him a British imperial hero or a white supremacist thug – only obscure matters further. A calmer and a closer look at this most divisive of national figures is something we could all use at the moment, as the nation state in question seeks to launch its comeback.

Just how ‘national’ was Drake? The charts used for the circumnavigation were Portuguese, Dutch and Spanish. There were Basque, French, Dutch, Danish, Scottish, Welsh and, as we’ve seen, Afro-Caribbean crew-members. The Spanish thought the Golden Hinde was of a French design. Drake’s pilots for the South American coast were Portuguese, Greek and indigenous. Neither were such transnational borrowings anything unusual. Ferdinand Magellan’s crew 60 years earlier comprised at least eight different nationalities. Is it meaningful to speak of these voyages as ‘national’ ventures at all?

Yes, in so far as they were deliberate moves in a contest between rivalrous European states. Drake’s backers, for example, made a 4,700% return on their money and clearly felt that the circumnavigation had served the national (as identified with their own) interests. It allowed Elizabeth to snub Catholic Spain, the world’s only superpower, and pay off the entire national debt.

J. M. Keynes wrote in 1930 that ‘the modern age opened with the accumulation of capital in the 16th century’. Specifically, he traced ‘the beginnings of British foreign investment to the treasure which Drake stole from Spain in 1580… every pound which Drake brought home has now become £100,000.’ That’s nearer £500,000 in 2018 money.

There is important truth in this. Yet this ‘triumph’ of economics was not a foregone conclusion. The Privy Council, which was summoned when the ship got back, advised that the treasure should be returned. That Drake tried to bribe members of the Council suggests he was seriously worried. The bribes were refused. Investors in the voyage eventually won Elizabeth round but it was a close-run affair.

Another of the ‘established facts’ about Drake is that, to the Spanish, he was ‘the Dragon’, an emblem of Diabolus. Yet one Spanish seaman who encountered him in the Pacific described him later as ‘one of the greatest mariners that sail the seas, both as a navigator and as a commander’. A (Spanish) observer of his daring raid on Cadiz marvelled at the way he led his ships out of the harbour ‘as well as the most experienced local pilot’. Pedro Sarmiento, one of Spain’s foremost mariners, described him as ‘well versed in all modes of navigation’.

Back in England, he certainly had a way with the home crowd: ‘the people swarming daily in the streets to behold him, swearing hatred to all that misliked him,’ wrote one contemporary. But he put up money to endow a lectureship in navigation, too, and there were more discerning admirers. It was the scientist William Gilbert who hailed him ‘our most illustrious Neptune’. The mariner John Davis, who had himself taken a ship both ways through the Straits of Magellan, ranked his achievements as a navigator with those of the greatest mathematicians, engineers and artists of the age – ‘a man of great practise and rare resolution’, he called him. Even William Borough, another navigator, with whom Drake quarrelled bitterly, allowed him ‘equal to any [seamen] that live’.

When English guards told their Spanish captives that Drake was a sorcerer, was that just a wind-up or partly the expression of a shared unease? English folktales about his magical powers abound: at the Armada’s approach he cut chips of wood into Plymouth Sound by night, which at once became warships fully armed and manned. The story is a patriotic tribute but it surely betrays a deeper unease, too.

Mathematics and engineering were viewed by the public as akin to magic. Indeed, many of their practitioners at this time also subscribed to ideas we would regard as magical. About the emergence of modern science the philosopher Hannah Arendt once wrote that ‘both despair and triumph are inherent in the same event’. Humans had ‘found a way to act on the earth and within terrestrial nature as though we dispose of it from outside’.

The result was an unnerving shift. Science put at humankind’s disposal hitherto unimaginable power. Wrecked and looted Spanish cities, from Corunna to Santo Domingo, bore testimony to Drake’s abuse of that power. But such abuses did not go unchallenged, even at home. Given his wealth and influence, it should be no surprise that those who ‘misliked’ him made their criticisms in coded form.

As Mayor of Plymouth from September 1581, Drake set up a compass on Plymouth Hoe. Robert Norman, renowned compass-maker and a protégé of William Borough’s, wrote The Loadstone’s Challenge and published it in the same month. His poem takes a sceptical look at those who value precious stones more highly than the science which has made long-range voyages possible.

The French botanist Carolus Clusius visited London in 1581 to interview Drake and his crew about the peoples and the plants and the animals they had seen. There is no mention of any silver or gold in the fascinating text which he wrote, in Latin, about what they told him.

Notes on the voyage made by the chaplain on board the Golden Hinde, Francis Fletcher, offer an enchanting account of the giant shoals of flying fish and tuna encountered in mid-Atlantic, pursued by flocks of birds and pods of dolphins. This was, Fletcher comments, quite unlike anything predicted by the ancients. Astonishment is everywhere in his description of these scenes. The flying fish are still there in the official version of the voyage, published nearly 50 years later. They still provide some picturesque backdrop, but the excitement and the immediacy have been edited out.

Why? Because those who controlled the meaning of the voyage saw it – and we as a consequence see it still – as exclusively a matter of commerce and statecraft. One historian dismissed this section as ‘a digression about fish’. That clearly is not how it was for at least some members of the expedition.

Fletcher, like those courtiers at home, like William Borough, like others, quarrelled with Drake. That ‘the General’ employed his mastery of the new science for purposes of plunder is beyond question. But this unease about him, expressed in so many ways, by admirers and adversaries alike, points to something larger than any one person or country. It suggests a civilisation being made both rich and anxious by technological advance and a new predatory individualism. In other words, it points to an unease that is with us still.

At the far end of that globalisation process which began in the 16th century, we know as they could not have that the ‘infinite’ abundance encountered on their voyages would prove illusory. Given the enormity of what they were setting in motion, their national vanity now appears shockingly parochial. But the burden, then, is on us to find a better way. To condemn indiscriminately people who could not have known what we do now is little more, at this stage, than a disguised attempt to exculpate ourselves.

The Paradoxal Compass, Horatio Morpurgo’s book about the Elizabethan explorers, is out with Notting Hill Editions, priced £14.99