In 1875, weavers fighting for better pay knew exactly who to blame for their exploitation. Women.

Rather than blaming employers who forced women into economic competition with men by paying them less, or uniting with the women to fight back, they wrote angry anonymous letters to the Englishwoman’s Review (trolls had to make more effort before social media), threatening to ‘knock out the brains’ of women ‘taking’ male jobs. The Review retorted that ‘even the tiger suffers the tigress to hunt in his jungle’ (a pretty sick 19th century burn).

A century earlier, it was accepted that women did and should work: ‘..only a fool’, it was said, ‘would marry a women who could not earn her bread.’

What happened in between was a mass of manipulation, and the invention of a misogynistic ideology that still affects us today.

Before industrialisation changed everything, women’s labour was less visible – and therefore more acceptable. A woman working on a farm, often alongside male relatives and rarely seeing any real wage, was a great deal less alarming than hordes of ebullient ‘factory girls’ parading the streets of towns and cities arm in arm, signalling a new kind of female independence.

The Victorians looked at these new urban centres and saw poverty, overcrowding and disease, children dying at alarming rates, and – that great Victorian obsession – prostitution. They settled, like the weavers, on blaming women.

If women went ‘back’ to the home, they reasoned, all would be well. Employers would be unable to use them as cheap labour and, in something of a non sequitur, would accordingly start paying men a ‘breadwinner’ wage sufficient to sustain the whole family. Women would be free to devote themselves to hearth and home and this – also a bit of a reach – would mean men would eschew the pub and other temptations. Demand for prostitution, and domestic violence, would magically cease once women ‘did their duty’.

Various interest groups, including philanthropists and the church, warmed to this theme, portraying the domestic role as ordained by God for women, who could only be the moral centre of the family, keeping everyone on the straight and narrow, from the kitchen.

The darkest side of this was a division of women into good and bad, respectable and not, that lingers today. It was even asserted that ‘good’ women would not be sexually assaulted because their virtue would protect them – men would be gentlemen if only women were ladies, the thinking went. It was an audacious piece of victim-blaming, the echoes of which are still heard today when tabloids chew over rape cases.

It is said that well-behaved women seldom make history. But the truth is a bit more complicated than that. Sometimes, we have chosen to remember well-behaved women – if only because the alternative is just too threatening.

In 1888, 1,400 women who were supposed to be powerless and the ‘lowest of the low’ took on their exploitative, powerful national employer – and won.

The victory of the Bryant and May matchwomen’s short strike against appalling, unsafe conditions and management bullying sent shockwaves through the firm and the country, and beyond. The union they had demanded the right to form was the largest of women and girls in the country at the time.

This was ‘a turning point in our industrial history’, said one newspaper; and hundreds of thousands of workers from Ireland to Australia rushed to follow the matchwomen’s example, using strike action to unionise.

There was just one problem: the matchwomen were the wrong sort of heroines. That many were migrants (of largely Irish origin) was bad enough; but they also hailed from the East End, that terrifying abyss of poverty and crime, and were ‘factory girls’, commonly regarded as akin to prostitutes.

‘Slummers’ – well-to-do folk paying to tour poor neighbourhoods – believed they saw in areas like the East End not people like themselves enduring degrading conditions, but a different race. Feckless, criminal and the cause of its own misery, it threatened to overwhelm and corrupt the ‘pure’ blood of the better sort of Briton. Its women were ‘rough’ – they drank, fought and used foul language, and were surely immoral in their sexual behaviour as well.

In fact it would have taken a saint not to drink or swear in those conditions – and women and girls who couldn’t fight certainly wouldn’t thrive. Sexual assault and violence were common in the unlit streets, and not just from working-class men: upper class paedophiles and sexual predators too used it as a hunting ground.

But gentle passivity was an essential ingredient of idealised Victorian femininity, and the matchwomen weren’t living up to it. Gradually, subtly, their momentous victory began to be buried by history.

Even after working class history began to be taken seriously from the 1950s, historians either ignored the strike or mentioned it only in passing. Usually precise academics were slapdash with the facts, getting the dates wrong and writing for example that ‘a few dozen girls’, rather than 1,400 women, came out.

The next charge made was that the strike influenced no-one because the matchwomen were ‘too different’ from the workers who went on to form the new unions. This is frankly bizarre, unless by ‘different’ we understand ‘lacking penises’.

The dock workers who struck in 1889, and have been allowed their importance to the New Unionism movement, were also East Enders, ‘casual’ and sweated workers, and largely of Irish descent. Exactly like the matchwomen. A study of the census showed me that the two groups were not only neighbours, but that matchwomen and dockers often married, precisely because they had so much in common.

The third line of attack was the suggestion that the matchwomen’s strike was not, in fact, theirs, but foisted on them by Annie Besant, a middle class member of the Fabian political group who had written a damning exposé of Bryant and May’s business practices and working conditions.

This simply doesn’t withstand serious research. No lesser an authority than Besant herself said publicly that not only did she not lead the strike, she thought it a mistake. Nor were the matchwomen so gullible they would have agreed to go on strike just because a random posh lady said so, without strong guarantees for their financial support.

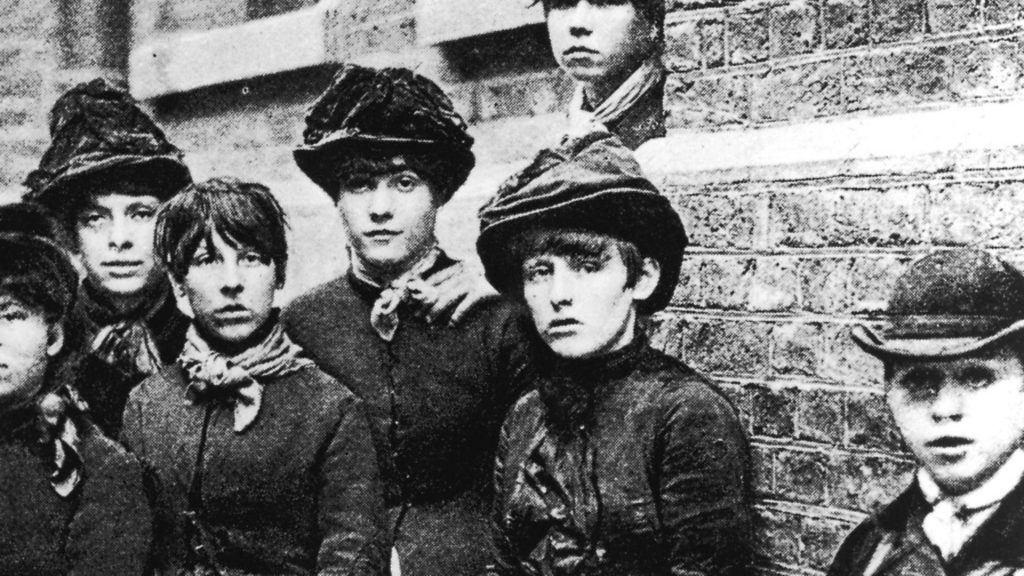

These were no ‘little matchgirls’, but women famous at the time for their strength, solidarity and sisterhood. They looked after one other, giving money, clothes and moral support when times were hard, and dancing and drinking together in pubs and music halls when they were better.

Their very appearance was a badge of identity – they had their own specific styles, and looking good was a matter of pride: they even established ‘feather clubs’ to buy and share communal hats, to be borrowed and worn for high days and holidays, as well as on the many socialist and Irish Home Rule demonstrations they frequented. Some of these women would undoubtedly have gone on to work for the vote – the East End was a hub of suffragette activity under the auspices of working class women like Julia Scurr, Minnie Lansbury, Daisy Parsons, Jessie Payne and Nellie Cressall.

But again, even as we celebrate the centenary of (some) women getting the vote, history continues to try to reframe the suffragettes too within the ‘Great Individuals’ school of history. An extremely diverse movement, peopled by working-class women and including an important component of Asian suffragettes, is often reduced to a handful of (undoubtedly influential but not exclusively so) Pankhursts.

In fact, the women of the East End were the saviours of at least one Pankhurst, rather than vice versa. The estimable Sylvia fled to the area seeking protection from the police when frequent arrests and force-feeding were taking a toll on her health.

Women surrounded the house where she was staying, and succeeded in menacing the police sufficiently that they retreated. When Special Branch then attempted to buy the use of rooms overlooking Sylvia’s residence from her desperately poor neighbours, they found no takers.

The suffragette campaign has been misunderstood in the same way as the ‘rough’ women of the Victorian East End once were. I’ve had very recent arguments about their ‘crazy’ and ‘violent’ behaviour in tactically employing arson and destruction of property. This was, in fact, a response not just to decades of lawful and wholly unsuccessful campaigning, but to brutal treatment by a state which regarded them as terrorists.

No suffragette, to my knowledge, ever beat, maimed, killed or sexually assaulted anyone in the course of their long campaign: yet this happened to them as a matter of policy.

In 1910, on what became known as Black Friday, 200 suffragettes were beaten and assaulted for several hours, with police deliberately targeting their breasts and lifting their skirts. May Billinghurst, a disabled suffragette, was thrown out of her wheelchair by police and attacked. This was not an exception: Sylvia Pankhurst remarked that suffragettes never returned from campaigning without being ‘black and blue’ from passing assaults by police and make bystanders.

While we might hope it to be a problem of the past, the desire to allow only the ‘right’ type of heroines into the history books has been visible too in coverage of the #MeToo campaign.

In fact the movement began not with movie stars in 2017, but in 2006 with woman of colour and feminist activist Tarana Burke, who had been sexually abused herself, and became the conduit for victims reclaiming their voices and power.

If we look beyond the mainstream narrative, beyond approved icons of femininity and ‘great individuals’, we will find not one or two, but literally thousands of stories of the extraordinary ‘ordinary’ women who have changed the world. That those in charge seem not to favour a history that demonstrates these women can be radical, unstoppable agents of change, is all the more reason why we should.

Dr Louise Raw is a historian, broadcaster, author of Striking a Light (Bloomsbury) on the 1888 matchwomen’s strike, and organiser of the annual London Matchwomen’s Festival, which takes place on June 30 in Bow