French dislike of the EU is more widespread that you might think. But it has taken on a different form to that seen in the UK

Claude doesn’t quite fit the clichéd view of eurosceptics: mild in manner with a mordant sense of humour and an ability to speak two languages, neither dispossessed, nor rich, he has run his own small business for three decades. He is also French.

Claude knows I am a journalist but I have always been a little vague about whom I write for – it gets tiresome listing foreign newspapers and explaining where each one sits in the market. I can’t remain vague today, as I have a copy of The New European with me; besides, I wanted to show him something in it, so I hand it over.

Ahah, he laughs. It’s like the Canard, he asks, looking at the front page cartoon. Le Canard Enchainé is a famous French satirical newspaper, more or less analogous to Private Eye, though perhaps more tied into the political establishment, which regularly uses it to leak embarrassing information. I reply in French: ‘No, it’s a paper against Brexit’.

Brexit! It’s great! It’s going well! The bourse [stockmarket] is soaring, he tells me.

There is a certain sadness beneath his reply, or at least it seems to me. Not because Britain is leaving the EU, but because he might like France to leave also but he knows it never will. Sangfroid, as they say.

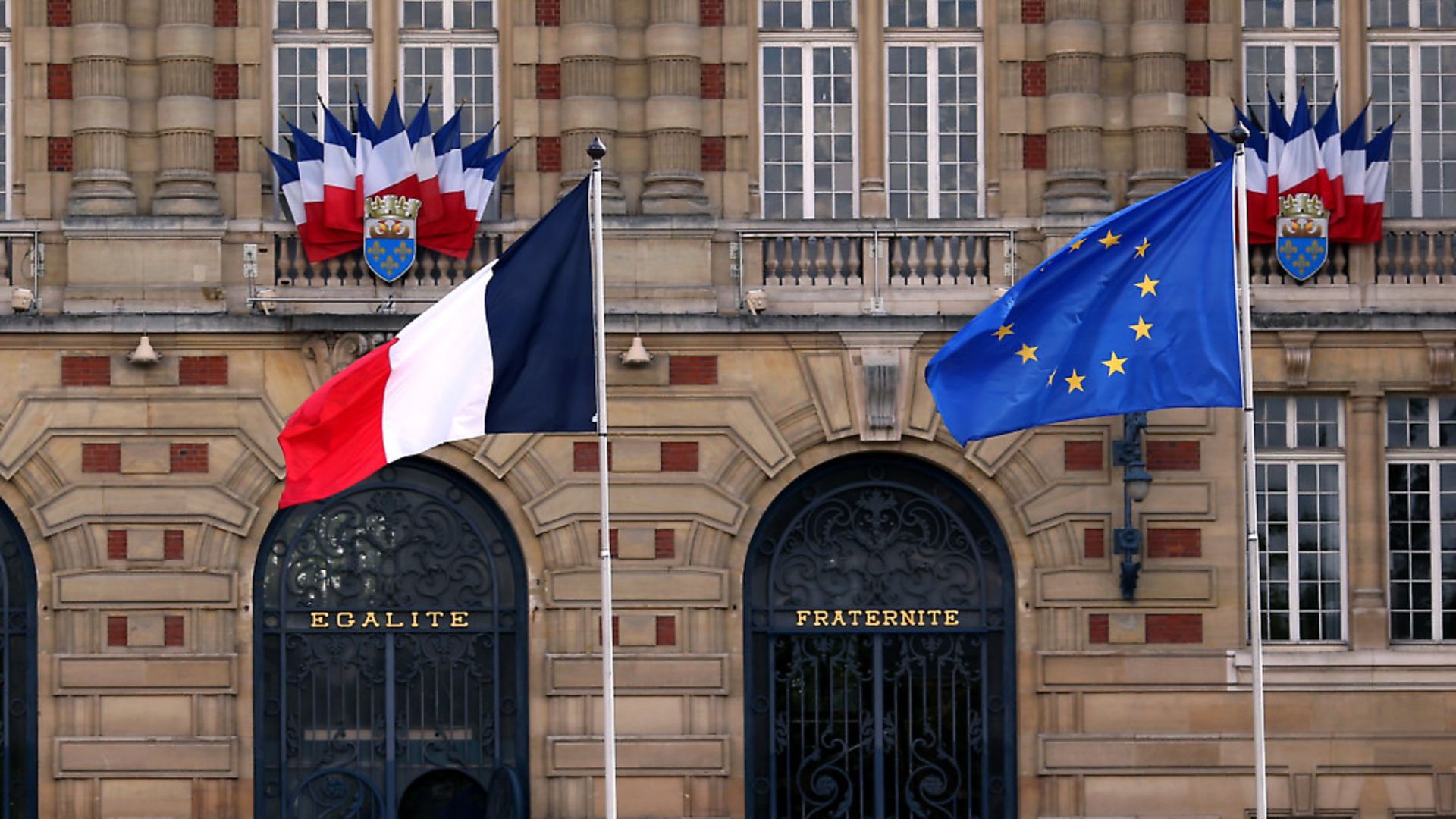

Claude is not alone. EU flags fly across Paris – it may be my imagination, but there seem to be more of them since the Brexit vote – but these have been raised by officialdom, not by legions of cheering europhiles.

Indeed, a Pew Global poll carried out shortly before the Brexit vote said 61% of French voters had an unfavourable view of the EU, well above the British result of 48%. Other polls taken since then show a slight improvement from the EU’s point of view. A TNS Sofres poll said 55% wanted to remain in the EU, 33% wanted to leave, with 12% undecided.

But if France has seen a ‘Brexit bounce’ in the EU’s favour it has been driven by fear, not love.

I asked Laetitia Strauch-Bonart, who writes for the newsweekly Le Point and regularly appears on Arte television in France, about the character of French euroscepticism. ‘[The] French don’t like EU much, but they live with it,’ she said.

In practice what this means, however, is that France seems to take what it wants from the EU while ignoring the parts it doesn’t like. If this is true, however, it is in part because as the EU has become more market-oriented it has moved away from France’s alternative vision – and away from French economic dominance.

A 2006 report by the think-tank Civitas accused France of undermining the European project. Among the charges was that the country repeatedly failed to transpose EU directives into French law and was ‘systematically undermining the four economic freedoms that underpin the operation of the single market’.

As France’s economy has come to be overshadowed by the German behemoth, France has, paradoxically, been pulled deeper into the EU. French protests about economic liberalisation are a given, but nostalgia for the post-war golden age of ‘les trente glorieuses’ (thirty glorious years) cannot alter the fact that France has to compete on the world stage, something EU membership helps it to do. Despite the clash of the background grumbling of euroscepticism and the loud europhilia of the establishment, the political reality in France is one of mere acquiescence.

‘The French ‘people’ are deeply eurosceptic, but at the same time they fear even more the consequences of a ‘Frexit’ on the economy. They subconsciously know that the EU helped the French economy and forced the country to implement reforms it would have never done otherwise,’ said Strauch-Bonart.

‘French people are not as brave – or foolish – as the British! Hence this disturbing Pew poll, where Euroscepticism seems higher in France, but leads to no action. In brief: lots of talk, little action,’ she said.

Perhaps French euroscecepticism is different from British precisely because France is so different from Britain. French commentator Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry turns the question on its head: it’s not that French euroscepticism is different, it is in Britain that it is different. He has a point, despite a few left-wing Brexiteers, Brexit was driven by a market-oriented vision of Britain’s future, whereas in Europe as a whole most eurosceptics want to tame the market.

‘One difference is that while both French and UK eurosceptics are pro-sovereignty and anti-immigration, UK eurosceptics are much more pro-trade, whereas French eurosceptics are more anti-trade,’ he said.

‘It’s also more cross-partisan here. Lots of Labour voters voted for Brexit but there’s no UK equivalent, that I’m aware of, of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the anti-EU French leftist.’

In fact the British far-left is fairly uniformly anti-EU, condemning it as a bosses’ club. The difference is that, unlike in France, Britain’s far-left is electorally insignificant. Britain’s Labour left, meanwhile, also long opposed EU membership but it was, until recently, very much on the back foot in the party. Leader Jeremy Corbyn is regularly accused of having failed to campaign enthusiastically against Brexit, but it is something of a wonder that he campaigned at all given his background in Labour’s Bennite wing.

In 1991 Tony Benn gave a speech to parliament, laying out his view in stark terms: ‘Some people genuinely believe that we shall never get social justice from the British Government, but we shall get it from Jacques Delors; They believe that a good king is better than a bad Parliament. I have never taken that view.’

However ambivalent the French may feel about the EU the chances of ‘Frexit’ seem remote, to say the least.

All of the mainstream candidates in this year’s presidential election are pro-EU, albeit to varying degrees, with only Marine Le Pen on the far-right and Jean-Luc Mélenchon on the far-left, along with a few minor parties, proposing a referendum offering eurosceptics the chance to crash the country out of the bloc.

If history is anything to go by French eurosceptics are unlikely to be asked. The last time Europe was put to the vote in France was in 2005, on the EU constitution, and it was resoundingly slapped down. The result was also ignored, with the constitution redrafted as the Lisbon Treaty and passed without a public vote.

Stung by the rejection, one of the EU constitution’s authors, the former president of France Valéry Giscard d’Estaing later said that the constitution was ‘practically unchanged’ in its new guise as a treaty.

‘The proposed institutional reforms, the only ones which mattered to the drafting convention, are all to be found in the Treaty of Lisbon. They have merely been ordered differently and split up between previous treaties.’

Giscard d’Estaing meant this as a pro-European statement: ‘When men and women with sweeping ambitions for Europe decide to make use of this treaty, they will be able to rekindle from the ashes of today the flame of a United Europe,’ he wrote in an article for The Independent.

However, the fact that in order to get the constitution past France’s electorate it had to be shunted into a dull, impenetrable treaty – and one which would not be subject to a referendum – says a lot about French attitudes to the EU.

Jason Walsh is a freelance journalist based in Paris