Still life may lack the drama and passion of other forms of art. But, as CLAUDIA PRITCHARD discovers at an exhibition of one of its great proponents, it is no less intense

Battle scenes, expansive nudes, eye-popping abstracts and ravishing views compete in the art gallery to catch the eye, with their scale of ambition, dizzying detail or boldness of execution.

A handful of jugs and jars sitting in a row, would not seem much of a rival for those virtuosic scenes.

Yet the vases, bottles and boxes of the Italian artist Giorgio Morandi have a pull of their own, and seem to belong silently to his own singular world.

The little vessels who peopled his modest studio were his models, painted time and time again.

Apparently unconnected even to the tables that bear them, they are, in fact, linked to centuries of art in several European countries, as a new exhibition at the Guggenheim in Bilbao demonstrates.

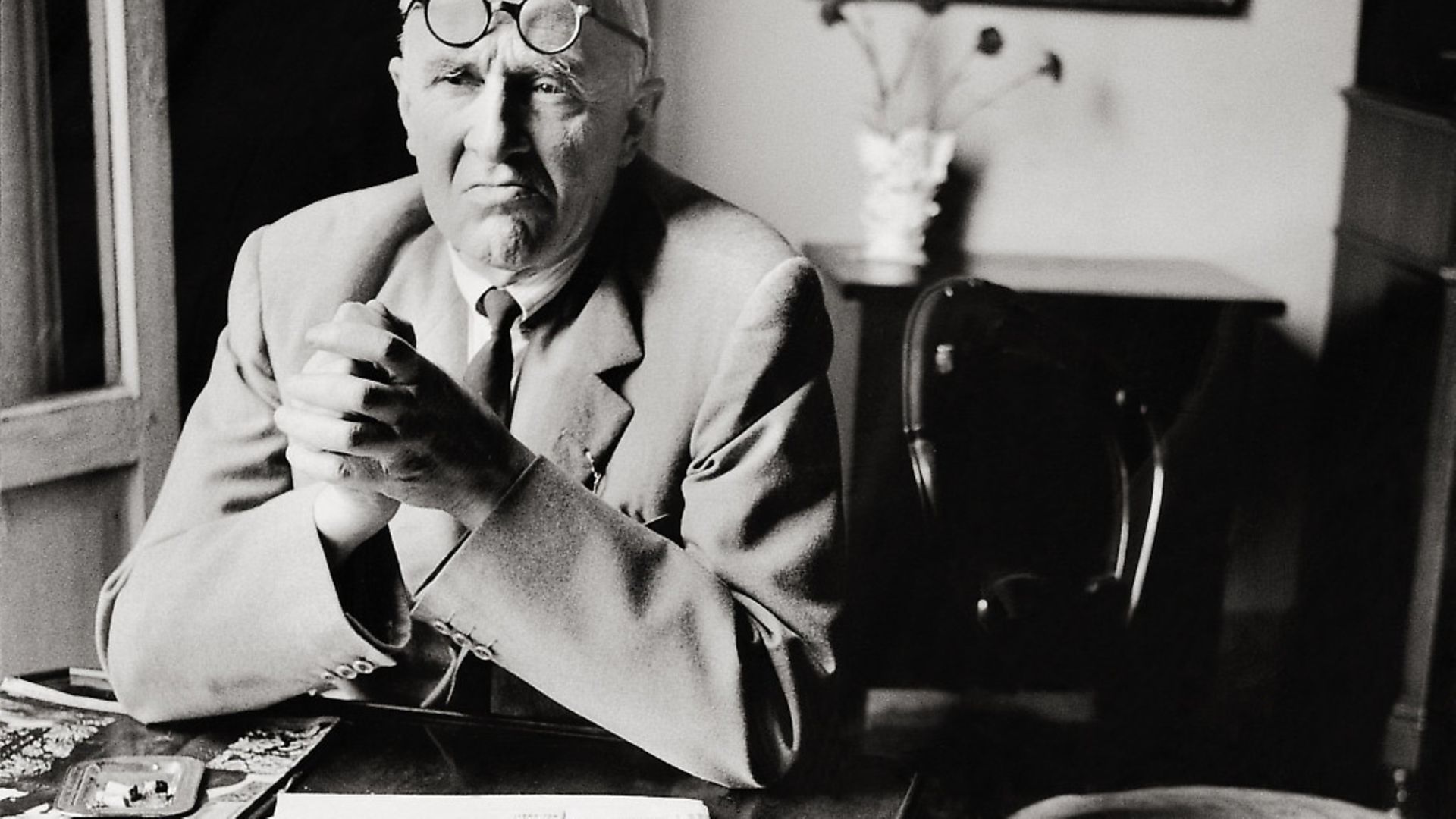

Born in 1890, Morandi himself never lived away from his native Bologna. He studied in the city, worked alongside other leading Italian Novecento artists, including Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi and Giorgio de Chirico, and fell in fleetingly with contemporary movements.

A brief flirtation with metaphysical painting, as practised by de Chirico, had passed by the early 1920s, and de Chirico would later admire the new path Morandi took, admiring his flair for ‘the metaphysics of the most ordinary objects’. But from a relatively early age Morandi forged his distinctive own way in the tradition of, above all, still life. And in doing so he drew widely from the work of those who had gone before him in not only Italy, but also France and Spain.

A Backward Glance: Giorgio Morandi and the Old Masters highlights three outstanding influences. The first of these owes much to a landmark exhibition of the Spanish Golden Age, staged in Rome in 1930 by Morandi’s friend, the art historian and critic Roberto Longhi. Paintings by El Greco, Murillo, Velázquez and Zurbarán were shown not alongside one of the city’s many historic collections but at the go-ahead Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, thereby claiming these 16th and 17th century artists for the modern age.

El Greco (1541-1614) proved to be particularly important to Morandi, who kept a book of tiny reproductions of the Spanish master’s works in his studio, admiring particularly the flower painting in a religious scene so full of incident and characters that the casual observer would overlook this little outburst of nature.

Morandi, too, practised flower painting, but as early as 1915 the oversized terra cotta jug with its arabesque handle outdoes the half a dozen buds in his Fiori (1915), and very soon other vases became more eye-catching than the few blooms they contain.

In the hierarchy in painting, defined by the French Royal Academy in the 17th century, still life came last: history paintings were king, followed by portraiture, genre scenes of domestic life, and landscape. An arrangement of food and tableware was considered lowly stuff. So it may seem like a big leap to Morandi’s quiet corners from the mannerist religious drama of Jacopo Bassano (1510-92) or the satins and lace of Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665-1747) or the sugary, homely domestic scenes of Pietro Longhi (1701-85), but these were Morandi’s outriders. He owned four small pictures by Crespi, a fellow Bolognese artist, and he admired their still life details.

Roberto Longhi, who took up a teaching post at the University of Bologna in 1934, published his history of Bolognese painting the following year. He concluded his chronology with Giorgio Morandi, whom he singled out for his ability to both mine the past and navigate ‘the most troublesome droughts’ of modern painting.

Morandi’s habit of taking away the seemingly insignificant detail was perhaps most pronounced in his way of seeing the great Guido Reni masterpiece, the Pala della Pesta (1630). Viewing it at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, recalled his friend Francesco Arcangeli, another art historian, who accompanied him, his attention was drawn away from the Virgin and Child, with adoring saints and Jesuits, to the minute depiction of his own city at the foot of the painting.

Bologna’s skyline is distinguished by its many towers, and the exhibition’s curators, Petra Joos in Bilbao and Vivien Greene at the Guggenheim in New York, see in his tightly packed still lifes the same outline, stepping up and down, the same low forms squatting before the elegant long necks of slender bottles.

While Dutch Golden Age painters defied the haughty prejudice against still life with their virtuosic displays of pithy fruit and gleaming glasses, Morandi seems to have been more influenced by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, whose natures mortes come alive at any moment. In his Kitchen Table (1746) the use of white, in a dead fowl, cloth and eggs, will resonate in the later artist’s own work.

Morandi’s colour palette moved through early browns and greens, as in his precocious Still Life of 1920, through lighter tones until he reached his most recognisable soft and powdery shades of blue, yellow and grey, always with white holding the picture. But those thick whites belie layers of colour, blues and reds, which give warmth and depth.

Helpfully displayed are replicas of favourite objects which, after Morandi’s death in 1964, remained in his Bologna home, now a museum. Closer inspection reveals that familiar motifs were given their visual appeal by Morandi himself. A white bottle proves to have been originally transparent, but has been swilled through with a milky wash; dumpy boxes with simple designs were handmade by the artist. An opaque bottle owes its colour to the application of brown paint.

It was Chardin again who fascinated Morandi with his series of paintings depicting a young man building a house of cards. The precarious fragility of life is summed up in this doomed undertaking, but Morandi makes his own cardboard forms, painted twice, first in their construction and then on canvas, endearingly solid, holding their own in any gallery. His simple objects stand immutable, moments of calm and little pots of balm in a churning world.

A Backward Glance: Giorgio Morandi and the Old Masters is at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (guggenheim-bilbao.es), until October 6