What you need to know on why the UK will go to the polls for the European Elections on May 23, how the elections work, the tactics at play and what it all means for Brexit.

If the Avengers are approaching their Endgame, this week marks the beginning of Remain’s civil war – the UK’s extension to the Article 50 process means the country will have to go to the polls on May 23 to elect a new batch of MEPs.

The process is set to be a brutal one, with Remain buffeted by a series of factors which act against it. This contest is one that, thanks to various structural and electoral forces, is stacked against pro-Remain parties.

Here is what you need to know on why this vote is happening, how it works, what the tactics in play are, and what it all means for Brexit. And, as a spoiler warning, the best outcome is that it means as little as possible.

Why we’re voting

The first thing to note is that if Theresa May gets her way, we still might not go to the polls on May 23 – but since when did Theresa May ever get her way?

When it became clear the UK would need a second extension to Article 50 – because MPs have failed to agree a deal, a second vote, or to revoke Article 50, but also agreed to rule out no-deal once again – the prime minister was keen to get only a short extension, and avoid a new election to the European parliament.

This is because the European elections have to happen at roughly the same time across all 28 EU nations (over a three-day period), and the new parliamentarians take their seats at the start of July. These MEPs then confirm the new EU commissioners – the team that actually run the show day-to-day – and the EU can’t function without them.

The EU was, therefore, worried that if the UK was still an EU member but didn’t have duly appointed MEPs then all of its activities could be subject to legal challenge, on the basis that they would be undemocratic (you may appreciate the irony), meaning that any extension beyond June makes holding the elections essential.

Given the termination date on the current extension is October, if the UK fails to agree a deal or revoke Brexit, that means that holding the MEP elections is a fundamental part of the deal.

Theresa May is still trying to avoid this by passing her deal before the election period proper for the European elections, by holding cross-party talks with Labour, but few think these have any prospect of success. As a result, we’re heading for the polls.

The votes

MEPs are elected for five-year terms, and all 28 EU countries have slightly different systems – though all use some form of proportional representation. In the UK, the Euro elections are often the means for smaller parties (like the Greens) to get electoral representatives beyond local government level, and have often been used as a form of protest vote.

UKIP, for example, were the largest party in the 2014 vote, despite their MEPs often being embroiled in scandals, and having dismally low attendance at the parliament.

Turnout is traditionally quite low, which means that voters tend to be older and more small-c conservative than for general elections – though this time could, of course, be different.

The UK’s system for electing MEPs is something of a set-up to favour larger parties, and to look similar to the first-past-the-post system that UK voters are used to.

Rather than ranking candidates in preference order, or picking multiple candidates, voters back just one party at the ballot box, with an ‘x’.

But rather than electing just one MEP, the UK has been split into large regions, each of which elects up to 10 MEPs. The system used to turn votes into seats is a variation of what’s called the D’Hondt system – which basically gives the first seat to the winning party, then halves its total of votes, and sees who has won the second time, gives them a seat, and halves their total.

This process keeps going until all the seats are allocated. If it was done across the UK as a whole – and as MEPs don’t have constituency duties, there’s no reason it couldn’t be – this would work to allocate seats quite fairly across the country.

But by breaking into relatively small regions, it favours bigger parties, as if small parties split the vote, they often fall below the threshold to pick up a seat, even if they pick up millions of votes across the country.

Each party in EU elections ranks its candidates in each region on a list. For big parties, whoever is top on the list in a given region has a very high chance of being elected, and anyone lower than third (and often third itself) has virtually zero chance of getting in, handing a lot of control to party managers who can put their preferred choices high up.

Here’s how it works in an imaginary example of a region with three seats:

The blue party gets 16,000 votes, red gets 11,000, and then the green, pink, yellow and purple parties all get 7,000 votes each. The first seat goes to blue, as they have the most votes, and their total is halved to 8,000. The second seat goes to red, with their 11,000 votes, which are now halved to 5,500. The third and final seat goes to blue, whose total of 8,000 votes is now the highest.

The red and blue parties managed to take all three seats, with blue getting the top two people on its list elected, despite red and blue collectively getting 1,000 votes fewer than the smaller four parties.

This spells a big problem for Remain.

The bad news

The dangers of the EU elections voting system was spotted by many pro-Remain commentators once the votes became a likelihood, leading for calls for smaller parties to band together and run as a coalition to maximise the number of seats they would win.

A proposal of this sort would work to maximise the number of seats ‘Remain’ would secure, by having just one list of pro-Remain candidates in each region – presumably shuffling which party was at the head of the list in each region, so that there was a good scatter of candidates.

The problem is almost no party showed any interest in such co-operation, though the Liberal Democrats claim they offered talks to other parties (which other party leaders have denied). One issue for the avowedly pro-Remain parties, like the Greens, Lib Dems, Change UK, and SNP and Plaid Cymru, is that Euro elections are their big chance to show off their platforms and policies under a system in which they can win seats. If your party isn’t even viable under this system, why should it ever be treated as viable?

Another issue is that the parties simply don’t agree on issues beyond Brexit – and MEPs won’t have much actual say over the Brexit process, short of ratifying (alongside the MEPs from all 27 other nations) any final exit deal.

Given that, it’s strange to team up with a rival party you disagree with on other issues for the sole purpose of furthering an issue the MEPs selected won’t have much influence over. For a new party like Change UK, which needs to show itself as a new alternative to, say, the Lib Dems, teaming up with that party at their first time at the ballot box would be particularly difficult.

As a result, there’s no formal alliance. Each of the pro-Remain parties is fighting its own campaign for its own votes. Given Brexit will be the dominant issue of the elections, that essentially means a whole lot of infighting, with no real way around it. The result has been a race to get media-friendly faces on the MEP selection lists – to get your pro-Remain (and the same is happening on Leave’s side) candidate booked on shows, rather than another party’s.

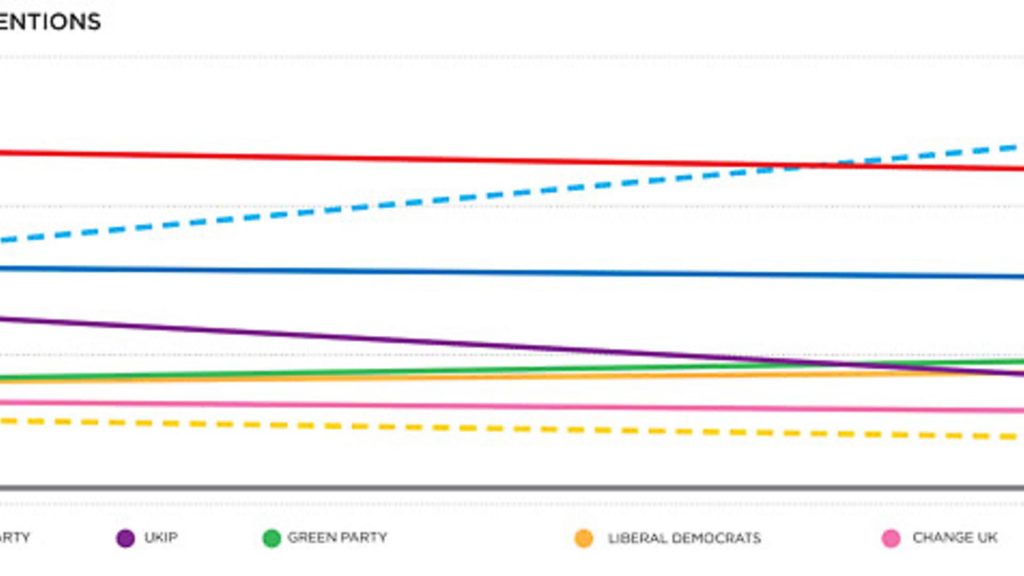

This problem is made worse by the polling. Nigel Farage’s new party has a clear name and message, and looks very likely to be the ‘winner’ of the elections – and take the most seats: in a vote dominated by Brexit as an issue, the Brexit Party is a winning name. It doesn’t even need a slogan.

By contrast, ‘Change UK – The Independent Group’ risks looking insipid, and is polling at around 8-9%. In most regions, the threshold to win a seat is higher than this, and several Remain parties are polling near this level. There is a big risk of pro-Remain parties wiping each other out.

All of this is before factoring in the Labour problem, a party whose formal policy is to pursue Brexit with no second referendum if it becomes the government, to ask for a second referendum on Theresa May’s deal, if she changed it to a deal they like (puzzling), but which is fielding pro-EU candidates for the MEP elections.

Does a vote for Labour count as a vote for Leave, for Remain, or neither? Or will all sides just try to claim those voters?

What it means

The situation isn’t as bad as it might look – or at least it doesn’t have to be. The Leave side has divisions of its own, even if the Brexit Party is a frontrunner: the Conservatives and UKIP are still there to split the vote.

Tactical voting is a plan starting to gain some traction among some Remainers. But without formal coordination, under this system it is as likely to cost pro-Remain parties a seat (accidentally knocking a party just under a voting threshold, for example) as to gain them one. At this stage, people are better voting for the party they like best.

But given the electorate and the maths of the system, the sensible tactic for pro-Remain parties may be to try to shift the turf of the contest. This is an EU election, to elect representatives to set EU policy. These are not the people who will decide Brexit – so why elect people who think their job shouldn’t exist, and who experience tells us won’t show up?

Such a message, if it broke through, could serve to demoralise Leave voters who don’t want MEPs, but more importantly for Remainers serve to weaken a pro-Leave party victory in these elections – this vote should not be framed as the battle for the future of Brexit, at least not if Remain wants to win.

The pro-Brexit parties will try to frame this contest as a confirmation of the 2016 vote, as proof the public wanted Brexit then and still wants it now. Laying the groundwork against that, and refusing to take part in that narrative is perhaps the next thing the pro-Remain parties can do for their voters.

That, and keeping their political war civil.