Let’s not go back to the fascism of the 1930s

https://twitter.com/TheNewEuropean/status/806219249022812162

Amid all the intricate discussion of Article 50 and Brexit terms, it is easy to forget why the European Union was formed in the first place. The ambitious aim was for it to end the cycle of war that blighted Europe for centuries.

My awareness of the EU’s remarkable role in transforming our continent from war-torn destitution to peace and prosperity grew while working as a representative of the UK government to the EU during the early 2000s.

The job I did in Brussels was by far the dullest of my 20-year diplomatic career. It mostly involved interminable meetings listening to 25 national delegates detailing their positions on obscure European programmes. These views were then laboriously brought together into a consensus.

In those pre-smartphone days, my coping mechanisms for these meetings included hiding magazines inside my briefing papers and using the simultaneous translation headset as a free teach-yourself Estonian course.

The faint whiff floating in from Antoine’s chip stand down the road was another welcome, albeit tortuous, distraction that turned thoughts to lunch by about 10.30 in the morning.

But I soon realised the value of this boredom when I visited the battlefield sites in nearby Flanders. There, the names of thousands of people from backgrounds like mine are recorded on a multitude of gravestones and sombre memorials to their sacrifice.

The world wars were a continuation of the way European relations had been conducted for centuries. Shifting alliances between countries were regularly punctuated by brutal conflicts over territory and resources.

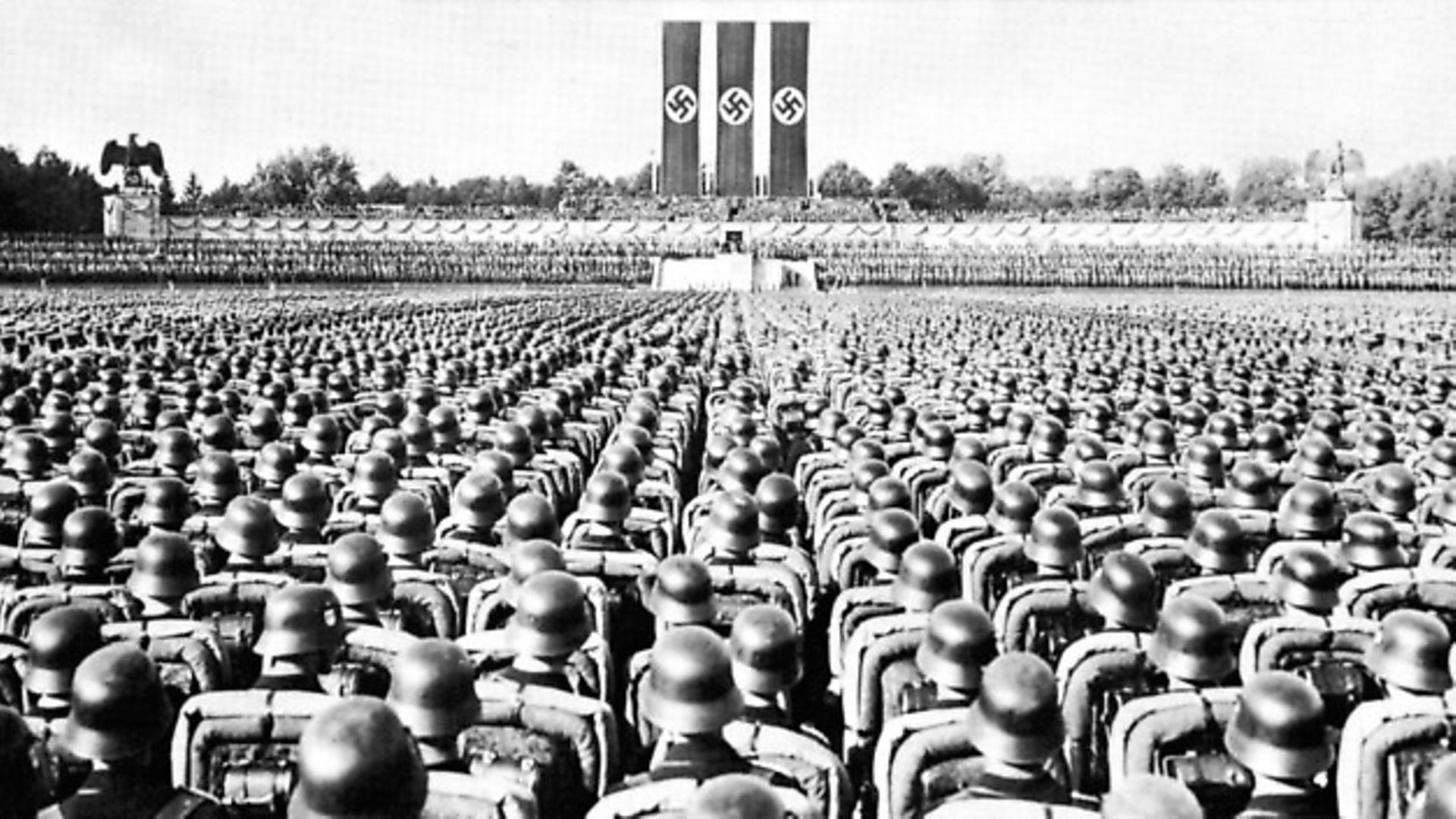

By the time the First World War broke out, military technology had advanced sufficiently to kill millions rather than thousands. The post-war horror at what had happened gave rise to the famous slogan ‘never again’. Tragically, nothing effective was done to stop ‘never again’ turning into ‘yet again’ twenty years later, when ongoing rivalry and economic crisis led to the rise of fascism, the Second World War and sixty million more deaths.

The founding of the European Coal and Steel Community, the forerunner of the EU, in the aftermath of that later war, was inspired by statesmen such as Winston Churchill, Konrad Adenauer and Jean Monnet. Their vision of reconciling old adversaries, through rules-based cooperation and pooling resources in the mutual interest, has ensured that there have been no further wars between EU members.

During these decades of peace, the attraction of EU membership has helped democracy and freedom to spread across Europe, from the defeated Second World War fascist dictatorships of Italy and Germany, to countries like Spain and Portugal, where such regimes endured longer, and the nations of Central Europe that spent decades in the grip of Soviet communism.

The EU achieved these successes via a painstaking bureaucratic process of aligning laws, regulations and governance systems. Dull it might be, but if ever a continent needed to cut down on drama it was Europe, and the EU has been an astonishingly effective mechanism.

The history that led to the formation of the EU, and the fate of previous generations of people sent to mainland Europe to pursue Britain’s interests, was often in the back of my mind when I was stuck in those meetings in Brussels. We still argued with our fellow Europeans and never got everything we wanted.

But rather than suffering the hellish excitement of war in sodden trenches, we got mind-bendingly bored in bland conference rooms. And, in the end, we always achieved a deal our countries could live with. Best of all, nobody died and none of our names were ever going to be inscribed on a monument to fallen heroes.

Sadly, though, the halcyon days of dullness are now over and we are entering an era of renewed risk. Losing the living memories of the generation that fought the Second World War is leading to the peace and democracy we have enjoyed since being taken for granted. But peace and democracy can easily be broken and Brexit is one of the cracks that are starting to appear.

While the leading Brexiteers are not fascists (they are not well-organised enough for a start), the rise across the continent of their ugly brand of nationalism does signify a movement in that direction. Indeed, it is disturbing just how many of the conditions that paved the way for fascism in the 1920s and 1930s are present again across much of the democratic world.

There is a widespread sense of economic insecurity. This clearly applies to the millions left behind by market fundamentalist economics. But it also covers many more people in ostensibly good jobs who know that their livelihood could be taken away in an instant. This insecurity will worsen as technological advances start to eat away at skilled and white collar employment.

It should not be forgotten that Nazism grew on the back of support from the fear-filled middle classes, rather than the workers who are more commonly blamed for such populist phenomena.

Racism and bigotry were never fully defeated. The age-old propensity to look for scapegoats and an ‘other’ to blame during times of trouble is now resurgent. Nor has it deviated from its traditional selection of entirely the wrong targets – people from different ethnic, religious or national backgrounds.

Simultaneously, our democratic institutions are suffering from a crisis of credibility. Governments, political parties, parliaments and the EU institutions have struggled to adapt to the speed and complexity of the modern world.

Too many politicians and civil servants are drawn from too narrow a section of society. This has led to the institutions of government being portrayed, sometimes justifiably, as being too close to unaccountable elites and little more than rubber stamps for their demands.

As in the 1930s, these problems are aggravated by the worsening extremism of political discourse.

There is now far too much incendiary speech about opponents being criminal and traitorous, rather than merely mistaken in their policy proposals. The customary partisan exaggeration is slipping into outright lying, a malaise that turned into an epidemic during the EU referendum campaign. Democracy is a contest between opposing ideas of what to do about an agreed set of facts. It breaks down when these conditions are not in place.

Other faint echoes of fascism can be found in the attempts to shut down debate about Brexit and the mainstream right’s misplaced confidence that they can manipulate extremists to their advantage. Ex-Prime Minister David Cameron called the EU referendum because he thought it would enable him to manage the far right. The hard-line posturing of his successor, Theresa May, suggests that she too believes she can ride this wave.

This does not yet come close to the catastrophic misjudgement of the 1930s German Chancellor Franz von Papen, who advocated Hitler as his successor believing that ‘we will push him so far into the corner he will squeak’. But it would still be reckless to ignore the early warning signs.

Our political system might just be going through a difficult transition phase. But history shows that events can easily accelerate out of control during times of upheaval. While remaining engaged with the details of the Brexit debate, we should remember the overriding reason for the EU’s formation and continue to struggle for its preservation.

Paul Knott is a former British diplomat and the author of The Accidental Diplomat; he lives in Switzerland