The great statesman adored the Côte d’Azur, where he indulged his passion for painting. Artist PAUL RAFFERTY, who has explored the area in search of the locations he painted, explains the profound connection between the man and the region.

August 1948, Aix-en-Provence, late afternoon, the baking heat now just about bearable. A convoy of artist, driver, valet, bodyguards and a Life magazine photographer rumbled down the three mile, pavé road towards Le Tholonet to the east of Aix-en-Provence.They stopped at a hairpin bend; for a moment the cicadas stopped with them.

After setting up the easel, parasol, whisky, soda, cigars, paints and brushes, table and chair and donning his trademark Stetson hat, Winston Churchill committed the iconic Montagne Sainte-Victoire to canvas.

Later, over dinner at the Hôtel Roi René at Aix with family and friends, he was deep in thought for several minutes. Suddenly, he broke into the conversation and said rather gravely: “I have had wonderful life, full of many achievements. Every ambition I’ve ever had has been fulfilled, save one.”

“Oh, dear me,” said Lady Churchill, “what is that?”

“I am not a great painter,” he replied. It was a touching admission of his feelings towards his art and one, I suspect, familiar to many artists, even the greatest.

It’s why painting holds such fascination and interest: it is never to be conquered; artists swim in the wake of the masters; for the artist all art is wholly subjective, while criticism of it can never be totally objective.

And as for Churchill, he was being – perhaps characteristically – down on himself. Not a great painter, certainly. But a very fine one, who’s work is certainly still valued today. Indeed, one of his paintings, The Tower Of The Koutoubia Mosque, was sold at auction in London earlier this month by the actress Angelina Jolie for £7m, smashing the previous record for a Churchill artwork, of £1.8m. Two more of Churchill’s paintings also went under the hammer, with the three together fetching £9.43m.

A notoriously energetic man, Churchill – a career army officer before entering politics – started to paint relatively late, at the age of 40. From then on, he was an industrious artist, painting when possible. He is perhaps most associated with Marrakesh where he painted The Tower Of The Koutoubia Mosque.

But his area of greatest artistic activity was the French Riviera, where I work as a professional artist. Painting much as Churchill did en plein air and in the studio, I have long felt an understanding and connection with this one facet of his life. And it was this that led me to research and write Winston Churchill: Painting on the French Riviera.

The book is part detective story, as I identify more than 40 unknown locations where Churchill painted landscapes.

One is the little harbour on the west side of St-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, a spot well-trodden by film stars, royalty, tourists and painters alike, where the late afternoon light dapples through the trees and sparkles on the deep blue Mediterranean.

By coincidence, it is a location I had painted myself, and perhaps a year later, while poring over a book of Churchill’s paintings, I suddenly recognised the scene. It was an experience that led me, over many months, to track down other spots along the Riviera which had inspired him, and to document them all in my book.

Churchill’s love affair with the Cote d’Azur began in the early 1920s on a painting expedition. Two years later he rented the Villa Rêve d’Or in Cannes for six months over winter and fell under the Riviera’s spell, drawn by the sun, the light and relative proximity to home.

For the next 40 years, staying with friends as an honoured guest in the finest châteaux and villas along the coast, he revelled in what he called the “paintatious” subjects all around him.

Throughout the years he spent on the Riviera, he mixed with the likes of Max Beaverbrook, Maxine Elliott, Lord Rothermere, Aristotle Onassis, Prince Rainer and Grace Kelly, Noel Coward, Charlie Chaplin, Somerset Maugham, H G Wells and the Duke of Windsor.

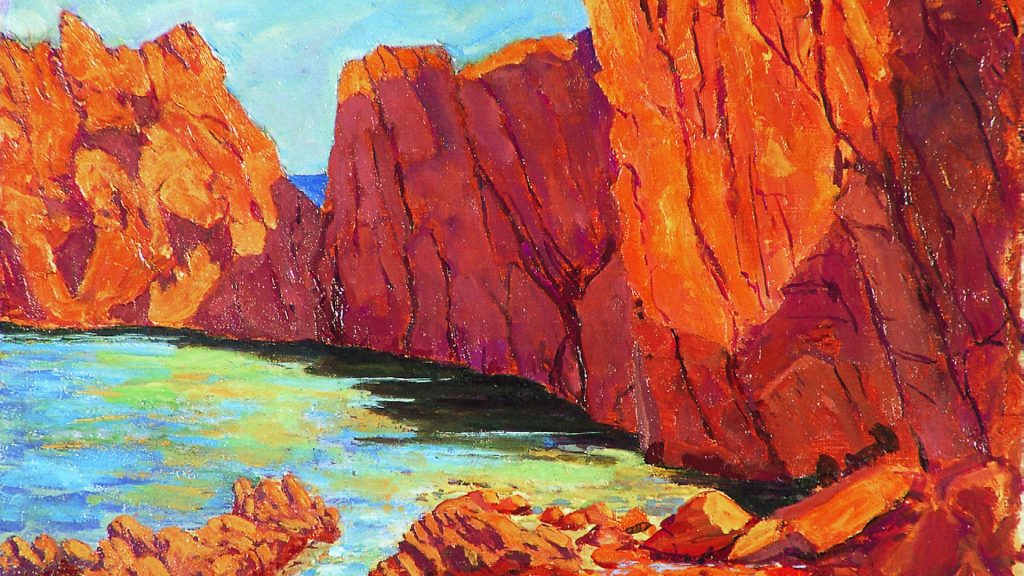

The 1930s were Churchill’s most prolific decade for painting, and he would venture out across the Riviera to paint his favourite locations: St-Paul-de-Vence, Plage de la Garoupe, The Red Rocks at Cap Roux, Saint Raphael.

He always painted with an entourage, consisting at least of a driver, bodyguard, valet and secretary, and often on arrival a gendarme or two.

His routine on the Riviera seemed to be much the same as his routine at home. He would rise late, dictate to secretaries, dine well and usually paint in the afternoon. Many of the locations that I discovered, the light is right with the painting in the late afternoon. If the weather was bad, he would write. When not painting, he would play bezique with his hosts and gamble in the casino. But it was painting which drew him here.

On location, with his entourage on standby, he would surrounded by his ‘draught excluder’ screen, sun parasols and painting paraphernalia and various forms of refreshment; an artist with his own caravanserai.

The fact that after the Second World War he was the most recognisable figure in Europe only added to the eccentricity of the scene, much appreciated by the small crowds who gathered in wonder at the sight before them.

Unimpressed, or simply not unrecognising him, one old Frenchman wandering past advised him that “with a few more lessons you will be quite good”.

Churchill modestly called his paintings “my little daubs”. When I first became aware of them, like many others, I was surprised he painted at all. My first thoughts were that some of his canvases were surprisingly good and others as amateurish as would be expected.

My opinions have evolved through following in his footsteps and I now judge them from a different perspective, by studying his canvases in depth and immersing myself in the actual locations. Very few of his works are straightforward; as a fellow artist, I often stand in awe at the difficult subjects he chose to paint: flowing water, flickering light, moving figures.

No paint-by-numbers, easy options painter, he. And, considering his late start as an artist and the fact that just occasionally he had other things on his mind, it is amazing that he captured these frequently fleeting subjects so well.

As he wrote in his book, Painting as a Pastime: “We cannot aspire to masterpieces. We may content ourselves with a joyride in a paint-box. And for this Audacity is the only ticket.”

So how did this audacity play out in practice?

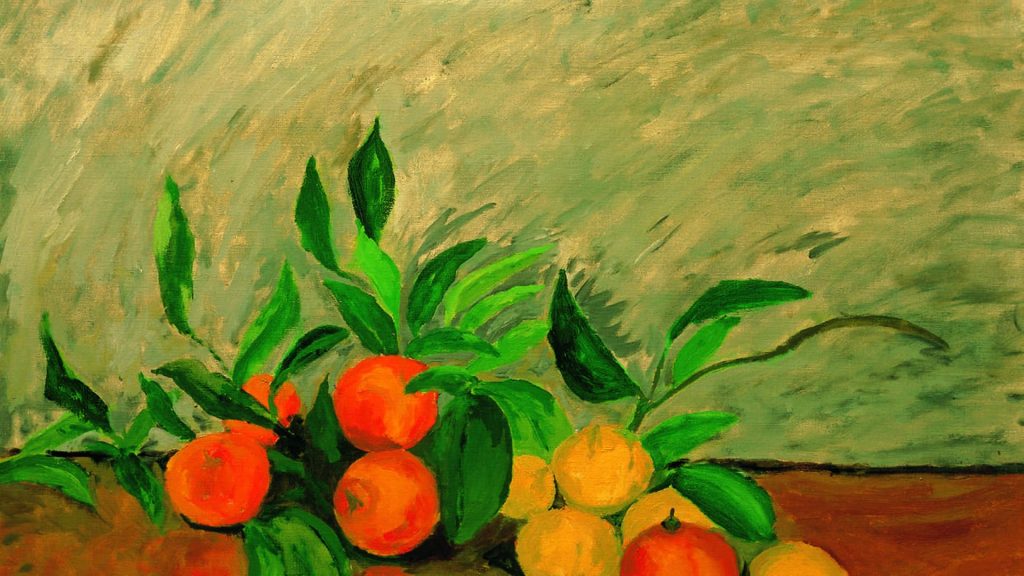

He worked directly on to a white canvas, with no ground colour. This is how the Impressionists worked, letting the lead white ground impart the most light through the oil paint. An aide squeezed out at least 15 colours in order on to his palette: along with his bright colours, there would be earth tints, ochres and neutral tints, but no black.

Churchill loved all the blues, Cobalt, French Ultramarine, Prussian and what he called the “British true blue – that cerulean, a heavenly colour we all admire so much”.

His tendency towards rather acid greens is evident in many canvases. (Though, in his defence, they often resemble their aide-mémoire photographs very well.) He routinely rounded out with Rose Madder, Vermillion Reds and Cadmium Yellows. Flake White from Blockx, recommended by his friend the painter Walter Sickert, would often be centre stage on the palette.

Churchill then mapped out the composition on the canvas, often with thin, linear lines in blue paint, after which he boldly laid in his colours with a large brush, likely thinning his paints with a half-and-half mixture of turpentine and linseed oil, as per Sickert’s instructions.

In photographs of him painting, he is often to be seen with one small glass cup, containing this thinning mixture, on his palette. His brushmarks were influenced by the Impressionists, direct, colourful and loose. He was trying to capture a moment in time, with the brilliant effects of strong lights and dark shadows exciting him most.

Thus his paintings had to be executed quickly: after two-hours the scene would change dramatically, especially at the time of day he favoured. Concentration and focus were needed. He would often complete a painting in two and a half hours.

If one was going badly he would grumble about it, and muttering “That’s no good”, scrape the offending part off with his palette knife, leaving a ghost impression, making a better attempt possible with subsequent layers.

In the final stages of a painting, he used a smaller brush to show details such as leaves and flowers, resting on his mahl stick as he enlivened the painting.

As the light faded he took the unfinished canvas back to base camp, and later, at home in his Chartwell studio he adjusted sections, or re-worked the whole. These paintings could become heavily impasted with thick paint, losing some of the transparency and freshness, much to Lady Churchill’s protestations.

Pamela Plowden, later Lady Lytton, one of several women who turned down young Winston’s proposal of marriage, said of him: “The first time you meet Winston you see all his faults, and the rest of your life you spend in discovering his virtues.”

A similar view could be made about his paintings. Only then can one study the works for what they are and see their attributes. Thus Churchill unintentionally checkmates the critic: to consider his art against that of a professional artist would be unfair; to consider it while bearing in mind his other achievements would be patronising.

In any event I think this misses the point and it is only when I studied his art from the perspective of a fellow artist, and spent time with them – and by extension him – on location, that I discovered their beauty.

They are large; some are bold and direct, others subtle and reflective. There is no pretence, no pandering. He is doing what he loved, as best he could and without restraint or expectation.

Churchill was about capturing what the artist Ralph Wormeley Curtis called his “fearless impressions”. This, more than any other adjective or statement said about Churchill’s paintings, encapsulates his approach.

His paintings have their own signature, or handwriting, as well as his own on them, a challenge for all artists, to have an individual voice, to make a work that is recognisably theirs. Some are simply striking, regardless of who painted them. So my opinions shifted from a passing intrigue to genuine respect and understanding.

Visiting Chartwell and the Studio Archive researching for this my book, I was struck by how well these paintings, these souvenirs of trips made and locations visited, so perfectly captured his time spent in those distant times and climes of that Golden Age of the French Riviera.

You are taken there, the mark of all good representational art. His canvases are stacked in the studio in varying states of finish, some no more than an outline with a few colour marks. His memory of the scene and light direction was uncanny. If finally satisfied with them, he framed and hung them at Chartwell or Hyde Park Gate for a time, until a new favourite came along, usually the most recent work.

I could almost sense the pleasure it must have given him on a cold and gloomy, rainy day in Kent to pull out a Riviera or Marrakech canvas and transport himself back to the heat and light, the landscapes and skies he so loved to capture in these paintings.

When Churchill first start painting, in 1915, it was a difficult time for him, in office but out of influence in the War Cabinet. Gallipoli was a recent memory. He was angry, frustrated, depressed, restless.

Then, as he recalled later in Painting as a Pastime: “The Muse of Painting came to my rescue – out of charity and out of chivalry, because after all she had had nothing to do with me – and said, ‘Are these toys any good to you? They amuse some people.’”

Churchill’s adventures with paint were not entirely autodidacte. His London neighbours, John and Hazel Lavery, were his first professional influence. All his artist friends gave encouragement, some with gentle words of advice such. Sickert wrote down explicit instructions on his methods which Churchill devoured, though he could not adopt to his sombre colours, preferring a bright coloured palette.

He also taught him to use a magic lantern to project a slide or negative on to the canvas, quite a revelation to Churchill. (When his bodyguard Ronald Goldman saw him using it in the studio, he said, “With respect, sir, it looks a bit like cheating”. Churchill was having none of it. From over the painting glasses he said solemnly: “If the finished product looks like a work of art, then it is a work of art, no matter how it has been achieved.”)

Painting, for Churchill, was more than creating art; it was also more than a passing pleasure, a pastime. It was a therapy for him, a tonic, a passion which enlivened him and never failed to hold his attention completely.

I don’t believe you can read into his paintings a message or even a mood. He did this for pleasure, he chose attractive subjects and not always easy motifs. The light and colour were his motivation and I feel a good distraction from what might have been worrying him.

If I were to read into his work, I would say they show a sensitive man, willing to challenge himself and bold enough to dive in and have a go.

Hours with a brush and palette in his hands were for him, according to his valet Norman McGowan, akin to being in paradise. Maybe not everyone’s idea of paradise as McGowan also observed, “He was painting. As usual he was grumbling all the time to himself. ‘That’s no good,’ he muttered and scraped off the oil paint again. It was an unwritten rule that no one ever looked over his shoulder. He could not stand it and made no bones about his feelings if anyone ventured too near.”

This was one area where Churchill the artist was uncharacteristically modest, always underestimating his own talents but quietly proud of his efforts all the same. This is born out in letters home to Clementine. He loved to send the canvases home before him and hoped she would wait for his return before opening them, so that they could unwrap them together for the big reveal.

It was a similar thrill for me, when researching my book, to discover a Riviera scene he had painted. When a location is found, it suddenly becomes obvious that this is it, as if it had been hiding in plain sight all the time. I cannot share enough the thrill of discovering an unknown Churchill location; still more so when visiting it for the first time, confirming my detective work and then soaking up the space.

For me, following in his footsteps on the Riviera, it has been a wonderful chance to discover his art and their locations. The search is not over yet, there remain a few elusive locations still to find. It is a rich field: only nearing the age of 90, after as many as 600 or more canvases painted, did Churchill retire his brushes, unable to muster the focus and physical effort painting demanded of him. I like to think that now, looking out over the beguiling blues of the Mediterranean Sea, he would still be questioning, ‘How would I paint that?’

This article is based on an extract from Paul Rafferty’s book, Winston Churchill: Painting the Riviera, published in 2020 by Unicorn. It is being released in French later this year by Albin Michel

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

CHURCHILL’S CONTEMPORARIES

Hitler produced hundreds of paintings when trying to earn a living as an artist in Vienna, in the years leading up to the First World War. He sought admission to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in the 1900s but was rejected twice.

Franco’s painting pastime is less well known. This secret hobby came to light in 2011, with the publication of a book written by his grandson, who described how the Caudillo had been encouraged to paint by his personal physician, as a way to relax from the stresses of governing.

Dwight Eisenhower took up painting in earnest in 1948. He is said to have been encouraged to take his hobby more seriously by Churchill – although, like Franco, he may also have been following doctor’s orders in using the activity as a means of stress relief.

Eisenhower, who became US president in 1953, claimed he had the most opportunity to paint when he was in the White House, because his time was so well managed.