The music of the Danish capital, like the city itself, is characterised by an extraordinary imagination and by flights of fantasy

Despite being practically-minded enough to have made Denmark one of the countries with the highest quality of life in the world, the Danes also understand the power of imagination. Their most famous son and master of fantasy, Hans Christian Andersen, lies in the capital’s Assistens cemetery but his spirit is everywhere in Copenhagen, from the major thoroughfare H. C. Andersens Boulevard to the waterside Little Mermaid statue.

In music too, the Danes have proved that they have imaginative range, from outlandish metal with a taste for the macabre fitting of Andresen’s tales of witches, dramatic deaths, and amputated feet dancing in red shoes, to Europop that veers to the cartoon end of fantasy.

In the 1970s, Copenhagen became the home of an attempt at utopia worthy of Andersen’s imagined worlds. Social change had come to Denmark like everywhere else in the previous decade. In 1964, Situationists cut the head off the Little Mermaid and the streets of Copenhagen filled with student protests against the war in Vietnam as the decade rolled on. When a B-52 carrying nuclear bombs crashed near the American Thule Air Base on Danish-held Greenland, anti-Americanism intensified.

Pornography was legalised in Denmark in 1969, and it became a European centre of the industry. In April 1970 the feminist Rødstrømpebevægelsen (Red Stocking Movement) demonstrated in the city centre against patriarchally enforced domestic drudgery (one of their slogans was “Only wash your own socks”). Meanwhile, visionary local architect Jan Gehl’s ideas for pedestrianisation were beginning to be put into action, transforming Copenhagen into the highly liveable city it is today.

It was another wave of student protests in 1971 that led to the occupation of Christiania, an ex-army barracks in the Christianshavn area. It rapidly became a commune with its own mini government and the open selling of drugs – an ideal society, as its founders imagined it. Local bands like the Cream-inspired Young Flowers and the psychedelia-meets-Dylan of Steppeulvene provided the soundtrack to Christiania’s early days, but by the late 1970s it had become the natural home of the city’s punk scene.

At Christiania’s Rockmaskinen (‘Rock Machine’) venue and Moonfisher bar, bands like Sods, who rapidly moved in a post-punk direction, and the chaotic nihilists No Knox, played early gigs. Both bands would appear on the seminal 1979 Pære Punk compilation of bands from this scene alongside another important local band, Brats, who would go on to become one of the architects of a new brand of metal.

Punk four-piece Brats had already adopted a heavier sound reminiscent of Judas Priest and Iron Maiden when King Diamond (aka Kim Bendix Petersen) of local outfit Black Rose joined as vocalist in 1980. By the next year they had changed their name to Mercyful Fate and were carving out a niche for themselves not only with Petersen’s jaw-droppingly operatic falsetto vocal but their macabre stageshow.

Petersen had grasped the power of fantasy in rock some years before. Seeing Alice Cooper at Copenhagen’s Falkoner Theatre on his Welcome to My Nightmare Tour in 1975 – a famously elaborate show of giant spiderwebs, marauding monsters and dancing skeletons, with Cooper in his signature stage make-up in the centre of it all – had been formative. Petersen later said: “Even though there wasn’t that much make-up it changed him completely. He became unreal. I thought if I could just reach out and touch his boot, he would probably disappear.”

Keen to secure some of this magic for himself, Petersen had already began experimenting with grisly onstage stunts during his time in Black Rose, pulling pig guts out of the bodies of dummies and adopting Cooper-esque black and white face paint. Petersen even fashioned a trademark mic stand out of real human leg bones. It was under his impetus that Mercyful Fate embraced Satanic themes, debut album Melissa (1983) including songs like Into the Coven, describing a Satanic initiation ritual, and follow-up Don’t Break the Oath (1984) adopting similar motifs.

Mercyful Fate split after their second album, founding guitarist Hank Shermann somewhat sick of all the Satanism, but Petersen took half the band with him to form the epnymous King Diamond, whose 1986 debut LP Fatal Portrait opened with sinister chanting and Hammer Horror organ music. The band would take the Satanism to greater extremes and for Petersen it was all rather more sincere than the pantomime stage act made it seem – he joined Anton LaVey’s Church of Satan in 1988. That same year, rather more prosaically, guitarist Michael Denner left the band to open a record shop, Beat Bop Records, near the University of Copenhagen, which is still going.

King Diamond and Mercyful Fate claimed a place on the continuum of shock rock that went from Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Arthur Brown via Alice Cooper to Kiss and eventually Marilyn Manson, but Petersen’s Satanism and ‘corpse paint’ look also anticipated the seminal Norwegian black metal bands, including Mayhem and Darkthrone, who produced some of the most extreme metal music ever made.

A raft of American thrash and death metal bands have also claimed Mercyful Fate as an influence, and closer to home, they foreshadowed the schlocky horror of Copenhagen psychobillies Nekromantix (frontman Kim Nekroman is known for playing a coffin-shaped double bass).

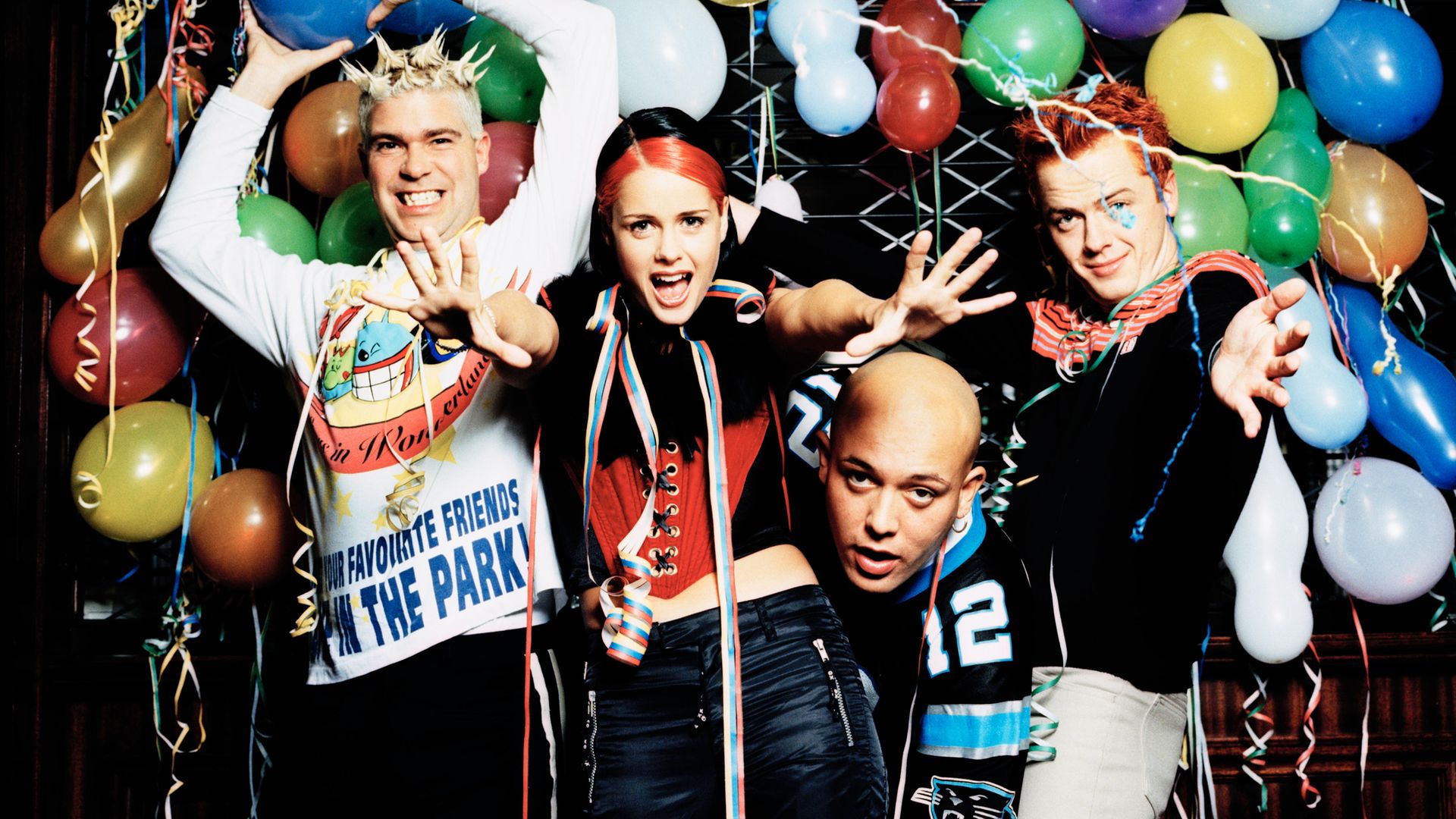

Such theatrics have not been restricted to the dark and the gothic. Forming in Copenhagen the same year the city made its first foray into the realm of dangerously catchy pop mega hits via University of Copenhagen graduate Sannie Carlson, aka Whigfield, whose Saturday Night was a four-week UK No. 1 in the autumn of 1994, pop four-piece Aqua had a keen sense of fantasy, but of a more childlike variety.

Initially named Joyspeed, Aqua’s first release was a happy hardcore version of the nursery rhyme Incy Wincy Spider (1995) which sunk without trace, probably with good reason. Singles Roses Are Red (1996) and My Oh My (1997) launched them to domestic fame, but it was the helium voiced Barbie Girl (1997) which made them international stars. With the manifesto “Life in plastic, it’s fantastic” and a knowingly ultra-kitsch video, it was the embodiment of the retrospectively carefree late 1990s.

Barbie Girl made the Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 and knocked imperial period Spice Girls (Spice Up Your Life, no less) off the top spot to spend four weeks at UK No.1 in November 1997. Mattel tried to sue for damage to their brand, but saw their case thrown out by a wholly unsympathetic judge.

The success of Aqua’s two following singles made for a hat trick of UK chart toppers and the band’s self-penned Turn Back Time, the third of those No.1s, was a polished pop ballad which showed them capable of genuine affect for all their essential silliness. The LP Aquarium (1997), containing all three hits, went multi-platinum all over the world.

Cartoon Heroes (2000), with its high production values video, was their last hurrah, but their appearance at the Eurovision contest in Copenhagen in 2001 alongside local percussion duo Safri Duo, whose Played-A-Live (The Bongo Song) had been a European megahit the previous year, was perhaps their crowning moment. Introduced as a band that was known “from the North Pole to New Zealand”, they appeared to a record live audience of 35,000 at the Parken Stadium and a TV audience of around 100,000. It was a level of fame only the inane chuck-away pop single can secure.

Copenhagen remains a place where make-believe and fantasy can be found. Christiania still nominally clings to its utopian values, despite a creeping takeover by the state and becoming a major tourist attraction along the lines of Camden Lock. It is still intimately associated with music, its Grey Hall – the barrack’s 19th century riding hall – remaining a major live venue for the city.

Christiania has also been immortalised in song, LA ska punks NOFX referencing it on Anarchy Camp (2004), while the band Lukas Graham, whose single 7 Years was an international hit in 2016, filmed the video for their follow-up Mamma Said there.

The song recounted frontman Lukas Forchhammer’s upbringing in Christiania. The video opened with the words on the screen “Christiania is a magical place in Copenhagen”, but it seems apparent the whole city is suffused with magic.

DREAMS OF DENMARK

Danny Kaye’s Wonderful Copenhagen, from the movie Hans Christian Andersen (1953), was written by Guys and Dolls composer Frank Loesser, who had never actually been there. Only slightly less cinematic was Scott Walker’s Copenhagen from Scott 3 (1969). Walker intoned “Copenhagen, you’re the end/ Gone and made me a child again”, and the song fades out to a mention of “children’s carousels” and the sound of fairground organ music.