“I always follow an idea and if an idea tells me to use unusual combinations of instruments then I’ll do whatever works.”

Ennio Morricone was talking about the famous two-note trilled theme he composed and arranged for Sergio Leone’s 1966 western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

“I wanted to differentiate three timbres to represent each,” he said. “A silver flute, sounding sweet, is the good. The bad is the voices singing together, off key. The ocarina is the ugly.”

The sparseness of the soundtrack reflects the harsh desert landscape in which the film is set, the economy of composition echoing the terseness of the dialogue. In Morricone’s musical vision of the American West the spaces in between the notes mattered as much as the notes themselves. It allowed the listener to experience the scorching dry heat and thirst of an unforgiving landscape through music that flirted with minimalism and atonality yet became one of the most famous film soundtracks of all time.

If Leone revolutionised the genre with his spaghetti westerns Morricone did likewise for its music. Before the emergence of their collaboration during the 1960s westerns were sanitised representations of a brutal period in American history accompanied by expansive, sweeping orchestral themes. Leone and Morricone pared dialogue, action and music back to the minimum, combining their talents perfectly to create an atmosphere so taut, tense and sun-scorched the audience never felt comfortable in their seats, meaning Morricone was as much responsible for creating the spaghetti western as Leone, Clint Eastwood and the Almeria landscape itself.

He despised the term, though. To him they were Italian westerns.

The pair first collaborated on A Fistful of Dollars, released in 1964. They had actually been at school together in Rome as young children, although this had no influence on their working together.

“Sergio Leone didn’t recognise me at first,” recalled Morricone. “When he came round and asked me to write the music for A Fistful of Dollars, he didn’t know I was the same Morricone as the kid from school.”

While the pair were discussing the kind of sound Leone wanted for A Fistful of Dollars, Morricone played the director his arrangement of Peter Tevis’s 1962 version of Woody Guthrie’s Pastures of Plenty.

“That’s it,” declared Leone, thumping the table, “that’s the sound.”

“Some of the music was written before the film, which is unusual,” said Morricone in 2007. “Leone’s films were made that way because he wanted the music to be an important part of it: he often kept the scenes longer simply because he didn’t want the music to end. That’s why the films are so slow, because of the music.”

He might have had a low opinion of the project, at least in hindsight – “it’s the worst film Leone made and the worst score I ever did” – but A Fistful of Dollars set Morricone on the road to international fame and a career notable for combining variety with longevity.

Even in old age his output was relentless. He was 88 when he picked up his first and only Best Original Score Oscar for his work on Quentin Tarantino’s western The Hateful Eight and it’s estimated that he worked on more than 500 film soundtracks. In addition, he composed more than 100 works for the concert hall in which he was always striving to achieve “the highest ideals of composition”.

It’s a remarkable legacy, not least in how his prolificity never compromised the quality of his creations. Whether he was writing whimsical instrumental interludes for a light comedy or scoring works like his unsettling, discordant cantata Voices from the Silence, written in response to the September 11 terror attacks, Morricone’s work was always immaculate. Not that he ever thought he was truly prolific.

“The notion that I am a composer who writes a lot of things is true on one hand and not true on the other,” he said. “Maybe my time is better organized than other people’s. But compared to classical composers like Bach, Frescobaldi, Palestrina or Mozart I would define myself as unemployed.”

For an unemployed composer he compiled quite a CV. As well as Leone and Tarantino he wrote film music scores for great names like Pier Paolo Pasolini, Brian De Palma, Bernardo Bertolucci, Terrence Malick, Barry Levinson and John Carpenter, composing for films that ranged from La Cage aux Folles to The Battle of Algiers via The Mission. During particularly productive periods he would produce more than 20 film scores in a single year.

Yet Morricone was probably happiest when composing music not designed for the screen. He was a key member of the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, a collective of avant garde composers and musicians active from the mid-1960s to the dawn of the 1980s. While the collective enjoyed a revolving membership Morricone was a founder and a stalwart. Il Gruppo was determined to push the boundaries of musical composition and improvisation, producing music of discord and atonality using unusual instrumentation and experimental studio methods that led to a string of albums still popular today.

Il Gruppo was the perfect channel for Morricone’s innate musical curiosity. Even in old age he sought new instrument combinations, new tonalities and new soundscapes. He demonstrated a creditable openness to formats, genres and commissions, taking on projects as diverse as the official theme to the 1978 World Cup in Argentina and It Couldn’t Happen Here, a song he co-wrote with the Pet Shop Boys for their 1987 album Actually.

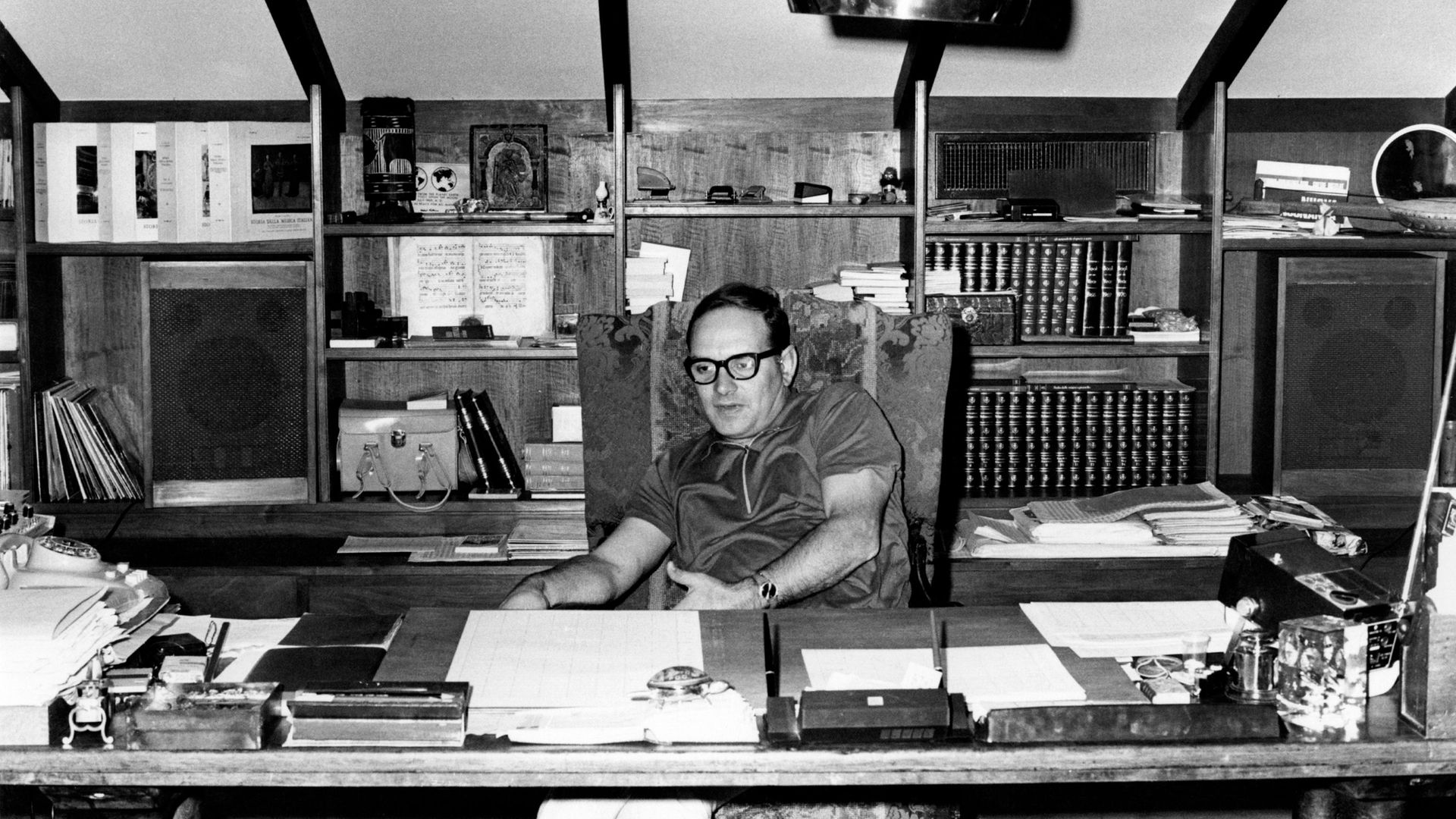

All this he achieved despite rarely leaving Rome. Hollywood tried repeatedly to tempt him across the Atlantic – he was frequently offered free use of a luxurious apartment – but the lure of the dollar never appealed. Rome remained his base and, effectively, his world. He was happiest there, squirreled away composing at his desk, hearing the music in his head so vividly he didn’t use so much as a piano during the creative process.

He was born in the city to a professional trumpet player father and a mother who ran a textile business. From the age of six Morricone was composing tunes and transcribing classical works he heard on the radio, leading to his admission to the Conservatorio Santa Cecilia to study the trumpet and composition at the age of 12. In his teens he started playing in jazz clubs and on graduation carved out a reputation as a gifted musical arranger. In 1958 he was hired by the Italian state broadcaster RAI but soon resigned – some say it was on his first day in the job – when he learned of a rule banning the broadcast of original compositions by company employees. He moved on to RCA and established himself as their Rome studio’s leading arranger.

During the 1960s Morricone composed for artists as diverse as Francoise Hardy and Demis Roussos, writing his first film soundtrack in 1961 to accompany Luciano Salce’s Il federale, ‘The Fascist’, and commencing a relationship with the director as productive as his work with Leone, even if it was never as well known.

Il federale also launched a career path that was never intended to endure.

“When I was 35 I told my wife Maria, OK, when I am 40 I will stop writing film music and just write absolute music,” he said in 2006. “But I am still here writing film music, so you can never say when you will stop.”

Even if he couldn’t say when he would stop he was at least prepared for it, having already written the public announcement of his own death when it came in 2020 at the age of 91.

“I, Ennio Morricone, am dead,” it began, prompting a global flurry of headlines and obituaries nearly all of which led with references to his theme for The Good, The Bad and the Ugly.

Yet it’s arguably the film’s climactic gunfight scene that showcases Morricone at his best. As the three protagonists face off wordlessly in the cracked, parched central arena of a remote cemetery, hands twitching next to their holsters, Morricone’s music builds the tension to an unbearable level with simple motifs of three or four notes, the tempo speeding and slowing, every cadence unresolved, a guitar, piano and trumpet all played so hard they’re barely in tune.

Leone’s camera closes in until we just see the characters’ eyes flicking back and forth, the music surging towards a climax that never comes because suddenly there’s silence, punctured by the lone, dry, throaty call of a crow.

It’s intense, it’s taut, it’s claustrophobic, it’s nerve-shredding and it’s Morricone at the peak of his powers.