Jason Solomons returns to the Croisette with movie reviews of Annette, Cow, The Worst Person In The World, Everything Went Fine, The Souvenir Part II, Jane by Charlotte and more

So much for the return of glamour. My Cannes started by spitting into a plastic tube in a makeshift Covid testing centre.

Due to political vagaries, British vaccination certificates weren’t valid at Cannes, so we were forced to test every 48 hours just to be let into the Palais des Festivals, hub of the action here at the end of the famous Croisette.

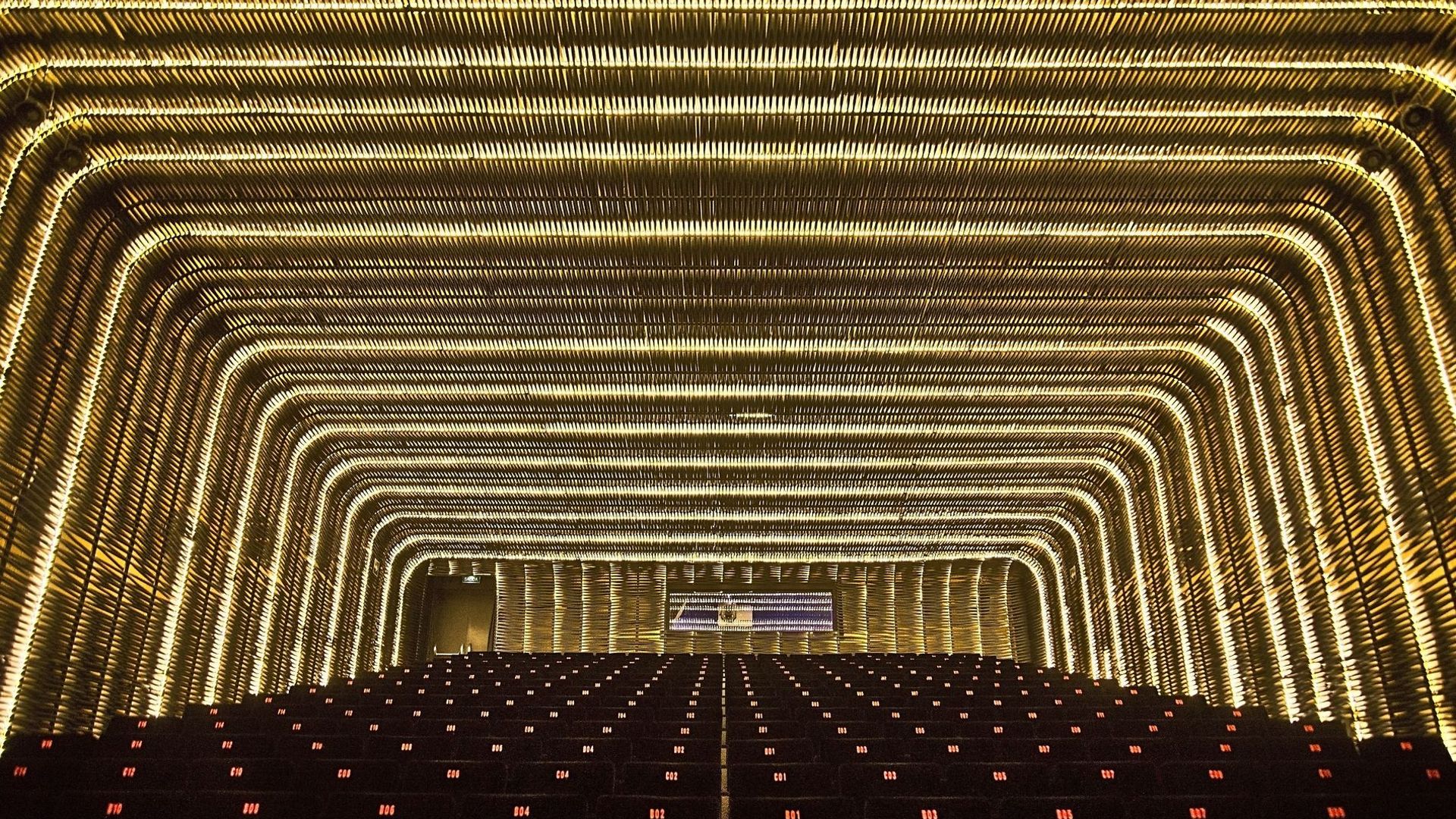

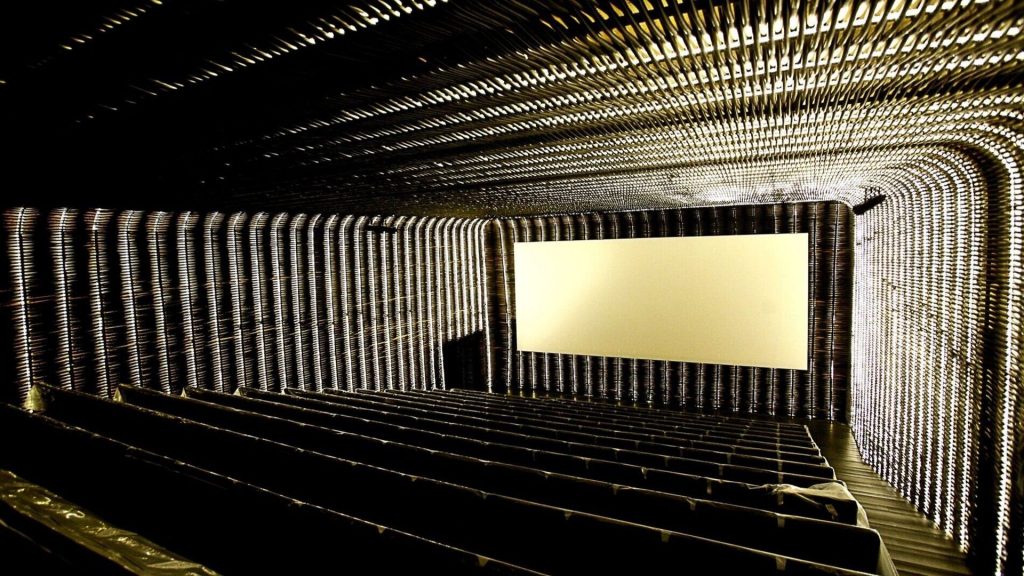

But the strange and seemingly random policies that have dogged these last few months of pandemic meant that in the building’s vast cinemas – the Lumber and the Debussy – delegates were packed in, seated next to each other, with no social distancing and a hastily recorded pre-screening announcement that we should wear our masks throughout.

The thing is: once the films were underway and the festival got into its stride over two years after Parasite won the Palme d’Or back in May 2019, the pandemic troubles quickly faded into the background. Cinema proved itself to be, as it always has done, the perfect form of escapism.

Until you have to spit into that plastic tube again. My second visit was less successful, producing a pinkish sort of liquid deemed unviable for testing. They told me it might be blood from my gums – it was more likely, I said, to be an excess of rose, the classic signature tipple of the festival which had made a welcome and surprising return with drinks receptions and official dinners (none of which could claim to be socially-distanced at all – nor were the gatherings in bars and pubs to watch the football).

I couldn’t believe it when I found myself at a party, an actual real party around a pool at a villa, with dancing and DJ and drinks, catching up with colleagues from press and film industry whom I hadn’t seen – or danced with – in two years and rubbing elbows with stars including director Andrea Arnold, jury member and Brazilian film-maker Kleber Mendonca Filho and the cast of a great new Norwegian film.

Such was the collective sense of relief that this rarified slice of fun and privilege was back that it was all most of us could do not to jump in the pool, like the old Cannes days. To be honest, the water didn’t look very clean anyway.

Maybe we’ll all get Covid. Maybe, after so long, nobody cares. Watching the movies, so many movies, lets us escape such realities. So let’s get to the movies and the glamour.

For the opening ceremony, there were stars and outfits and rousing speeches about the power of the movies. It ended with Pedro Almodovar, Jodie Foster (who charmed everyone with a speech in her fluent French), Jury president Spike Lee and Parasite director Bong Joon Ho, lined up on stage to declare the festival officially “open”, in four languages. Perfect casting.

I wish I could be so admiring of the opening film, Annette, by the notoriously unprolific French auteur Leos Carax (Mauvais Sang, Les Amants du Pont Neuf, Holy Motors) and starring Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard. The film is an anti-musical, for people who don’t like La La Land, for people who don’t like anything much at all, written by situationist pop ironists Sparks and featuring terrible songs terribly sung.

Driver plays a stand-up comedian whose material is – as so often in movies – wholly unfunny; Cotillard is an opera singer with a penchant for dying. They live in LA and, after a passionate affair, have a child played by a CGI wooden marionette.

I’ve searched my brains and asked many people here but I can’t fathom the symbolism or point of this at all, even with echoes of enduring fable Pinnochio. It’s creepy, yes, but also ridiculous and ugly.

The kid becomes a singing sensation (again, we have to take the film’s word for this because the voice is in no way remarkable) and the parents’ relationship destructs and Driver becomes a killer.

I hated it. I don’t mind a film that plays with the musical form – nor does Cannes, having rewarded The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, All That Jazz and Dancer in the Dark over the years – but you have to have some redeeming qualities and Annette simply has none.

Disappointing as it is to not like the opening film at Cannes, it’s also not uncommon nor disastrous as good films begin to amass in droves. It’s always tempting to divine some kind of theme in the selection, something with which to take the artistic temperature of the world, but there was little on screen to suggest the pandemic we’ve all been through – that drama was all off-screen – nor were there any particular threads of isolation or lockdown or collapse.

Mark Cousins, the documentary maker, had in fact been prolific through confinement and turned up to Cannes with two films celebrating the art of movies. The Story of Film: A New Generation featured clips from 97 works to illustrate what cinema has been up to in the 21st century, with advances in technology and form, looking at works from Frozen and Joker, to Bollywood, Thailand and Japan, covering all the genres, from documentary to comedy and horror. It was the perfect reminder of the skill and power of filmmaking to reflect on the human condition and the urge to tell stories.

Cousins’ other film looked at the life of one of British film’s most creative yet unheralded talents, producer Jeremy Thomas. The Storms of Jeremy Thomas follows the Oscar-winning impresario behind The Last Emperor, Crash, Sexy Beast, Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence and 60 more on his annual car drive from his Oxfordshire home down to his suite at Cannes’ Carlton Hotel, musing on life, death, controversy, sex and politics along the way. A very diverting doodle, with terrific analysis of much-admired and always challenging films.

Cannes is full of sidebars and distractions away from the main Competition. This year, having greedily squirrelled some choice talents for himself during the absence, Cannes boss Thierry Fremaux widened the official selection to 72 films, making it practically impossible to keep an eye on everything, particularly with the new online ticketing system and its glitches and crashes.

Pick a film, any film and let it hit you was the mantra. Even one about a cow.

Andrea Arnold, previously feted here for Red Road, Fish Tank and American Honey and now heading up the jury for the Un Certain Regard section, also premiered a documentary simply called Cow. Given her social realist form, this could well have been about a particularly unpleasant woman, with reference to Ken Loach’s Poor Cow or something – but no, it was about a cow.

And it was a brilliant, immersive work of art, too, focusing tightly on a beast called Luma and the undignified industrialised process she leads for a life on a dairy farm. For all the film’s seriousness, it did unleash a tide of puns (The Lives of Udders, something to chew on, streaming on Moo-bi… you take it from here) and is noteworthy for the drama that unfolds within the confines of this life, with birth scenes and tenderness and sex scenes as she’s goaded and prodded, branded and labelled. It even builds to a climax that could rival a Scorsese film.

In the early running for the Palme d’Or, I was swept away by a film from Norwegian director Joachim Trier. The Worst Person in the World is a romantic drama that follows Julie, a young woman dealing with life and relationships in Oslo. There’s something of Woody Allen in its urban tone and literary structure, divided into 12 chapters that narrate Julie’s emotional journey through boyfriends and affairs, all set in coffee shops, book stores, media launches and lovely lakeside summer houses. It features a breakout performance in her first major screen role for Renate Reinsve as Julie, certainly a leading contender for prizes.

It wouldn’t be a European film festival without a film from Francois Ozon, and sure enough, he delivered Everything Went Fine (Tout s’est bien passe) which starred Sophie Marceau. I fell in love with Sophie Marceau back at school when the French teacher suggested we all should subscribe to Paris Match and the first copy he brought in had her on the cover. If we really dig deep, I realise that moment is probably why I’m here, doing what I do, a realisation which came flooding back as soon as she appeared on the screen here, albeit cast against type in an unglamorous but finely judged performance as a daughter caring for her grumpy, 85-year-old father recovering from a stroke (powerful work from Andre Dussollier).

He asks her to help him “end it” and the film slowly becomes a beautiful family drama as well as a clear-eyed case for assisted suicide, told without sentimentality or melodrama yet with a soap opera style realism and some heightened, almost Almodovarian touches. It might not be the top prize winner but, in its muted way, as ever, it’s unlike Ozon’s previous work (even 2005’s Le Temps Qui Reste, about a terminally ill, young gay man) yet totally of his universe and wonderfully acted.

Having said there wasn’t an overarching theme to all these movies, maybe it’s us, the watcher, who bring the themes, foist our own readings on to what we see before us. As well as the Trier film, about a woman called Julie, there was another wonderful, romantic, coming-of-age film here at Cannes, also about a young woman called Julie. I’m talking about Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir Part II, which played in the Director’s Fortnight section and is a delicate, exquisite follow-up to her 2019 The Souvenir.

That first part was set in early 80s London as Julie started film school and a destructive relationship with a roguish boyfriend who turns out to be a junkie. Now, a few years later, she’s still recovering from the shock of that relationship and is trying to complete her graduation film, which is turning out to be a drama about the relationship instead of the gritty documentary of working lives she initially pitched her tutors.

It’s a gorgeous, gentle film about memory, class and family (Julie is played by Honor Swinton Byrne, daughter of Tilda Swinton, who plays her mother, Rosalind, in the movie) and what forms us, and about the need for connection, both physical and emotional. It’s this aspect that might resonate post-lockdown, this sense of finding one’s way again in the world, piecing back together what makes you, what you love.

And that theme was there in Jane by Charlotte, a documentary by daughter Charlotte Gainsbourg about her mother Jane Birkin, that feels like opening up a family album and sharing some deep feelings, particularly about the death of Kate Barry, Birkin’s first daughter, with the composer John Barry and who died in 2013.

It also literally opens up the past when the two visit Serge Gainsbourg’s old house, where they all lived once, and which has been left in the exact state it was the day Gainsbourg died, in 1991. It’s preserved – “like Pompeii,” remarks Birkin – with all the perfume bottles, medicines, tins of food, cans in the fridge and knick-knacks like a shop of curiosities, with tapestries and photos, including a huge one of Bardot, for whom Serge originally wrote Je t’aime non plus, and with which Birkin became an international symbol of sex, style and beauty.

The house will be open to the public as La Maison Gainsbourg later this year and any visitor will have to tread carefully. It looks like you can only get a couple of people in there at a time. I wouldn’t attempt to open the tins of sardines, though.