We don’t worry enough about giant monster attacks. Granted, we have problems enough, what with pestilence and political tumult, to be fretting over things whose actual existence is, at best, disputed, but if this year has taught us anything, it’s that nothing can be dismissed as impossible.

In lieu of more formal contingency planning, the best preparation for such assaults is the large body of work devoted to wargaming just such scenarios, the more than 60 years worth of monster movies, wherein civilisation is trashed by everything from radioactive dinosaurs to an oversized moth.

Some people will dismiss these films as obvious kiddie fare but they need to look a bit closer, because there’s more going on here. Monsters are more likely to attack at times when the wider world is preoccupied with thoughts of existential disaster, as though they wanted to supply commentary on potential doom.

Famously, the first cycle of movie monsters struck as the world grappled with potential annihilation by ‘the bomb’, and they’re usually taken as metaphors for atomic age destruction. Which is interesting because we’re currently in the midst of another monster boom: what does it say about our times that the likes of Pacific Rim and a re-awakened Godzilla are so popular?

This latest wave has been largely met with the same derision with which critics greeted their 1950s forebears, but that’s one of the things that makes them such an intriguing area of study: that such a disreputable genre can be used to convey such profound subjects.

They become more intriguing still when you see just how frequently these films explore other social and cultural subtexts, to the point when these often silly movies can genuinely be called ‘political’.

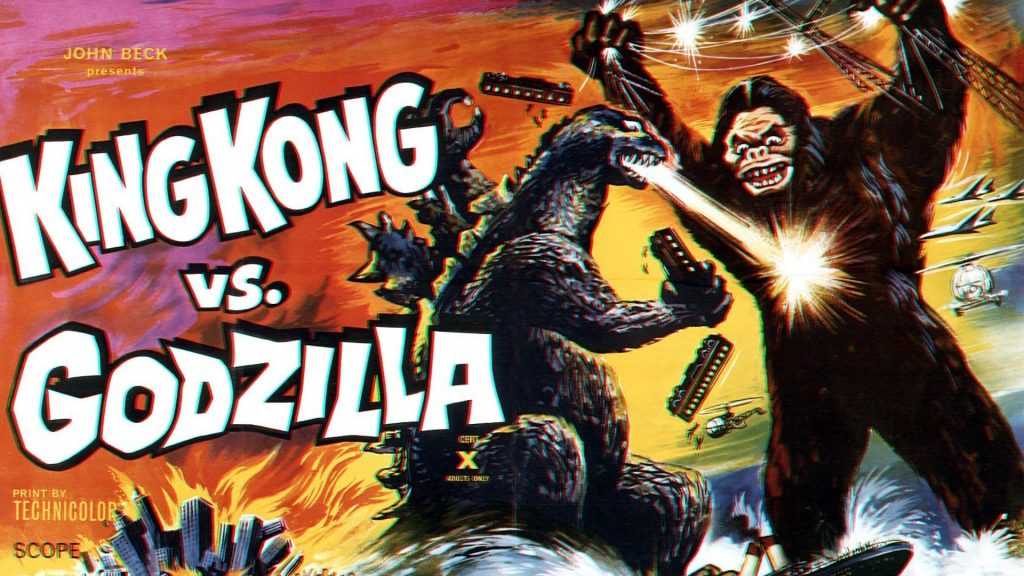

Let’s start at the top: most monster taxonomists trace things back to King Kong in 1933 and certainly, King Kong supplied the template many later movies would follow, with a vast beast (a giant gorilla here) causing significant destruction in a broadly recognisable setting (depression-era New York). What Kong did not do, however, was establish much in the way of imitation. It would be a long time – over 20 years, in fact – before anyone else made a monster movie worthy of the name, one that really catalysed the genre.

That would be The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, which reared its head in 1953. A clue to what might have inspired the filmmakers, and why it struck such a chord with original audiences, can be found within the first five minutes: it begins in the Arctic, where the US army is doing an atomic test.

The resultant blast did more than free the titular beast (later identified as a ‘Rhedosaurus’) from the permafrost where it had been hibernating. Here was a blunt statement of the destructive power unleashed by nuclear science (because that Rhedosaurus creates quite a bit of chaos before it’s finally zapped at Coney Island), one that firmly established the monster movie’s capacity to express contemporary issues and concerns.

Other monster movies followed in its wake, most of them imitating its central metaphor. By far the most interesting of those is Them! (1954), virtually the only American film of the cycle to go beyond expressing the terror of ‘the bomb’ to examine nuclear age society more broadly.

It is, by the standards of the genre, an unusually grim film, aimed more at grown-ups than the usual drive-in crowd. It begins with a couple of cops investigating some mysterious disappearances; the wind blows, tumbleweed rolls and strange noises are heard… It’s wonderfully atmospheric – and then a giant ant pokes its head into shot. Yup, Them! is the movie about giant ants, although the desert nest is only one colony. The race begins to find the others before they can destroy America.

Once again, nuclear testing is to blame for the monsters, but things are expanded with another exemplary metaphor: the ant is a hive creature, conformist and blindly obedient to its leader.

Although the filmmakers use black ants rather than red ones, they’re otherwise the perfect stand in, for that another great 1950s fear, communism.

What makes Them! so interesting, and so alarming, is how this threat is responded to. The military don’t simply take precedent over civic society but assimilate it: the cops and the FBI all slot neatly back into the machine. Other norms are abandoned for the greater good: a poor sod who saw flying ants is interned in a psychiatric hospital to keep him quiet. There’s no indication that he is released even after the threat is made public.

Happily, when the public are alerted, there is no mass panic. Everyone knows their place and does their duty, behaving exactly like the ants they want to defeat: conforming, accepting, obeying. Why, even the goggles that everyone wears in the desert makes them literally bug-eyed.

As ever with such readings, there’s the question of how far the filmmakers knew what they were doing and, as ever, the answer is the same: it doesn’t matter (trust the tale not the teller, and all that). You can take it as satire or endorsement of the values it expresses: it hardly matters – hindsight suggests that the conformity and unquestioning obeisance to men in uniform shown here is not an unfair depiction of Eisenhower’s America, a society craving a certainty that Cold War vagaries made difficult to provide.

The other great monster movie of 1954 is more straightforward. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms had been a big enough hit in Japan to inspire imitation. As in the American film, this beast would be a hibernating dinosaur freed (and irradiated) by an American bomb test, which then stomps a grand municipality (Tokyo in this case). There would, though, be a very different emphasis, as one might expect from a country that – uniquely – had experienced nuclear war.

Gojira – transliterated to Godzilla in English, as it shall be hereafter – is grimmer even than Them!: death rains down and children are shown as victims. Reports from original screenings suggest people routinely left in tears and no wonder: nine years after the surrender, here were the air raid sirens blaring all over again, presaging a new wave of implacable destruction. Those tears might as well be a manifestation of PTSD as testament to the power of the filmmaking.

For all it’s about a big lizard, the real subject is hard to miss. Geiger counters crackle throughout, there are irradiated kids and pointed mentions of Nagasaki. And while American audiences could trust that the military could dispose of their monsters, Godzilla is ultimately killed in an act of self-sacrifice, by a guilt-ridden character who has invented a weapon more powerful even than the atomic bomb and who cannot allow anyone else to know its secret.

Despite/because of all this, the film was a hit and so naturally there were sequels (the first 15 films have been gathered in a splendid box set from leading cineastes The Criterion Collection). But the grim tone would be progressively diluted for later films. Economic vicissitudes meant that the series was increasingly aimed at children who proved to be more attached to Godzilla than the grown-ups, probably because they had no memory of the war.

The films remain staunchly political, however, reflecting the times in which they were made. Relations with America remain a perennial, if touchy, topic; Japan had been burnt, nuked and then occupied by the US and, if Godzilla films are any guide, considerable resentment remained. It is often American activity, for instance, that frees Godzilla from wherever he ended the previous instalment.

In one of the Godzilla companion films, Mothra (1961) – coming soon on Blu Ray – America is lightly fictionalised as ‘Rolisica’, a hyper-capitalist and imperialist country. (Mothra – quite the best non-Godzilla monster, incidentally – partially flattens ‘New Kirk City’).

In the 1985 Godzilla re-boot (also called Godzilla), the US president pressures the Japanese prime minister to let them nuke Godzilla before the monster can threaten America. Instead, the PM prefers Japanese ingenuity, which deals with the monster far more safely.

Moreover, even though in real life the Americans have a mutual defence pact with the Japanese, they never actually help out in any these films, leaving things entirely up to Japanese troops. This is itself revealing, since the Japanese constitution, written by the Americans after the war, essentially forbids military engagement.

The exception is when it’s in self-defence, a category that includes attacks by monsters. The Self Defence Forces get mobilised throughout these films and while their success rate isn’t great, it’s hard – for Westerners, at least – to escape the feeling the filmmakers are allowing an officially pacifist country to celebrate its soldiers, tapping into that conservative nationalism that remains a potent, if necessarily discreet, part of Japanese politics.

While Godzilla is a global figure, he remains fundamentally Japanese. The most recent Japanese film, Shin Godzilla, was released in 2016, with Godzilla a stand-in for the catastrophes of 2011 (a tsunami, the Fukushima calamity), with well-aimed potshots taken at the political class along the way.

The films are firmly established as social commentary: given the tensions between Japan and their neighbours, it is a racing certainty that Godzilla will eventually battle a dragon or at least some other manifestation of Chinese power. China itself has steered clear of monster movies to date, although it’s worth noting that not every communist state has been so circumspect.

One of the strangest monster movies was made in North Korea. Pulgasari (1985) was made at the behest of hereditary despot Kim Jong-il (1941-2011), a huge fan of Godzilla: the production even hired Satsuma Kenpachiro, the actor who then played Godzilla to play the monster here. (Less orthodox means were taken to recruit its director: South Korean Shin Sang-ok was kidnapped and held in a labour camp until he agreed to helm the picture.)

Derived from a Korean folk-tale, it’s set in the distant past, when Korea was ruled by cruel feudal overlords. A peasant sculpts a small creature from rice; this is eventually brought to life (long story) and it develops a taste for iron. Once it’s eaten enough, it grows and grows and soon is big enough to help the peasants rise up against their evil oppressors. Hurrah!

One does not need a degree in semiotics to decode anything here: the friendly monster Pulgasari is a gargantuan stand-in for the Party, protecting the peasantry and ushering in a bounteous collectivised future. (Intriguingly, though, Pulgasari becomes a liability after victory – no longer able to scoff the iron weapons of the enemy, he feasts on farm tools instead, and must be destroyed: an acknowledgement that the Party is only a means to the end? Or Shin Sang-ok making mischief?)

Any film made in North Korea was always going to channel the thoughts of Chairman Kim, but the monster movie made it especially easy. More even than Godzilla, Pulgasari reveals the essential metaphorical space at the heart of the genre, just waiting to be filled by an idea.

This idea doesn’t have to be political: the recent Colossal (2017) uses the monster movie as a way of exploring self destructive behaviour and selfish male attitudes (although these days, that last bit might be political too…). However, the very dynamics of these films – the public spectacle, the necessary involvement of state representatives – act as a gravitational force for contemporary social issues.

That, surely, is why the genre is flourishing in the 21st century. There’s no shortage of material, after all. In fact the wall between ‘monster movies’ and ‘reality’ have never been so porous, with impossible, overwhelming threats coming from all directions and wreckage strewn all around.

In fact, the connections may be closer still: Abu Zubaydah was Al Qaeda’s operations chief. Later caught and interrogated by the CIA, he revealed that Al Qaeda’s original idea for a terrorist spectacle was to destroy “the bridge in the Godzilla movie”. They were, he revealed, struck by a sequence in the lamentable 1998 American Godzilla, where the monster destroys a bridge and wanted to do something on a similar scale. (Al Qaeda – terrible people, terrible taste in films.)

So perhaps it’s only appropriate that the best fictional reaction so far to the horrors of that day should be Cloverfield (2008), wherein we see a giant monster attack upon Manhattan through the lens of the citizen-journalist and his video camera. It’s as good an analogue as any for those still-unfathomable acts.

Then there’s the environment. That’s been a concern for Godzilla since Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971), where our boy tussles with a foul ‘smog monster’ created by industrial pollution. This theme has only become more pressing since, the impetus in The Host (2006, quite the best monster movie of recent years), Pacific Rim (2013), Godzilla (2014) and, most urgently of all, Godzilla King of the Monsters (2019), in which the bad monsters are explicitly associated with climate change and must be defeated by the less-bad monster (i.e. Big G).

And after the upheavals of 2016, it could be said that monsters really do walk among us. American political cartoonists, after all, have routinely depicted Trump as Godzilla – neither, after all, gives much thought to what they do nor the damage they cause. Meanwhile, our own dear prime minister has compared himself to the Hulk; not technically a monster, true, but big, green and wilfully destructive. Do we still need ‘metaphor’ anymore?

It cannot be stressed enough that the political component is but one part of the monster movie package. There are the aesthetic pleasures to savour, especially of those made in the years before computer generated imagery took over, when the special effects had a charmingly hand-made, artisanal quality. There is a simple joy in the sight of two rubbery monsters knocking seven bells out of each other, one that many of us have not tired of yet.

But it’s the subtexts that make them quite so intriguing, frequently reflecting the anxieties of their times more powerfully than many more respectable films. And they might even be a consolation: as long as movies are the only place where actual giant monsters attack, we can console ourselves that things aren’t that bad as they might be. That said, there are still two months in 2020 to get through yet…

Godzilla: The Showa Era-Films boxset is available now from the Criterion Collection; Mothra is available to pre-order from Eureka (eurekavideo.co.uk)