The unfailing brilliance of some of Europe’s greatest ever exports: cinematic villains, and villainesses

I blame Alan Rickman. The late British actor practically trademarked the sneering villain role back in the 1980s, first as Hans Gruber in Die Hard, then as the Sheriff of Nottingham (‘cancel the kitchen scraps for lepers, no more merciful beheadings … and call off Christmas’) stealing the show from Kevin Costner in 1991’s Robin Hood Prince of Thieves.

Rickman, who died earlier this year, paved the way for the Euro-villain in modern Hollywood and a host of British actors surely owe him a huge debt. Rickman and his disdainful dastardliness gave the studios a new sounding board off which to bounce American heroism.

By the time Die Hard With a Vengeance came along, Jeremy Irons was the baddie and he’d already been hired to voice one of the great villains in the form of Scar in The Lion King. Indeed, that cartoon criminal was merely following the tradition established by Disney in The Jungle Book, when George Sanders played Shere Khan. It’s interesting that in this year’s CGI remake of Rudyard Kipling’s jungle stories, the terrible tiger was again voice by a Brit, in Idris Elba, giving it a full Hackney growl – Shere Khan had gone street.

Jason Isaacs put the upper-class villain shtick to good use opposite Mel Gibson and Heath Ledger in The Patriot of 2000, illustrating how handy posh Britishness was for playing off the down-to-earth reliability of the Hollywood hero, the leading man, the American idol (even if that idol was sometimes Australian – which also reminds me of Basil Rathbone’s Guy of Gisborne taking on Errol Flynn’s thigh-slapping Robin Hood back in 1938).

The point is British villainy fits the bill. Most people somewhere in the world have beef against the British for a host of colonial-era invasions and pillages, and upper-class entitlement in particular has trampled out many an injustice on the poor commoner. Even in current non-Hollywood films such as Amma Asante’s A United Kingdom and Gurinder Chadha’s forthcoming Viceroy’s House, plummy Brits are to be despised – Jack Davenport with a pompous feather in his white army hat in Africa, Lord Mountbatten dressing for dinner in India.

But even way into the future, Hollywood knows British is still bad – Peter Cushing in Star Wars, Terence Stamp as General Zod, Ian Holm in Alien; and look at Benedict Cumberbatch in Star Trek and Tom Hiddlestone as Loki.

British baddies bring to the screen the threats of a classical education. There’s something inherently evil in their knowledge of Latin that must be brought down low by the plain-speaking everyman square-jawed simplicity of the Hollywood hero.

As well as at that Oxbridge education and imperfect teeth, Brits bring with them a dash of European sophistication that is to be both envied and despised: such sparkling exoticism and good luggage might be, initially, something to be admired, but in the long run, says the Hollywood script, it cannot come to good.

Noteworthy, though, is the possibility that the real European villain is perhaps most pronounced in female form.

Indeed, the very name for it requires European language: femme fatale. These seductresses include Marion Cotillard or Brigitte Bardot in Le Mepris, or Eva Green every time she steps on the screen.

No right-thinking American man can control themselves when faced with such screen sirens. It goes back to Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel, the soft purr of a foreign accent reducing the mid-Western male to jelly. (Or should that be jello?)

Think of Isabella Rossellini in Blue Velvet, or Claudia Cardinale, Sophia Loren, or Ornella Muti, or Nina van Pallandt in The Long Goodbye. Scandinavian goddesses, Italian beauties (here, one should always mention Monica Bellucci), French fancies and even Spanish smoulderers such as Penelope Cruz or Paz Vega, all of these embody a treacherous villainy designed to force the Hollywood male off the straight and narrow highway.

Even on the indie circuit, cool American auteurs reared on the likes of Anna Karina or Anouk Aimee, have been hung up on European dangers. Julie Delpy’s kooky Frenchness enchanted Ethan Hawke for decades in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise trilogy, her European baddie’s trick seemingly the ability to stay up late, talking.

And indie-style producer Harvey Weinstein knew how to harness European allure to hijack the Oscar system, turning Euro baddies into the classy currency of Oscar nominations, championing talents such as Juliette Binoche, Cotillard and Audrey Tatou and taking his brand of bluster to the Cannes Film Festival, where Europeanism is rife, where even films spoken in foreign languages dare to win prizes.

It’s no real irony that one of Weinstein’s biggest Cannes coups was to snaffle up the silent film The Artist for distribution before it had even played in competition – the mini-mogul made an exportable virtue of the film’s lack of French language and merely harnessed its gossamer French allure (Berenice Bejo, Jean DuJardin) to turn it into an Oscar-winning juggernaut.

Weinstein aside, the Euro-villain is perhaps best established in context opposite the British spy, mostly in James Bond. In order to throw Bond’s suave Britishness into bolder light, he’s been pitted against a series of accented baddies. There was Gert Frobe as Goldfinger, so low he even cheated at golf. But what about Lotte Lenya as Rosa Klebb in From Russia With Love (so beautifully lampooned by Mindy Sterling’s Frau Ferbissina in the Austin Powers movies) or that wonderful Anglo-French actor Michael Lonsdale as Hugo Drax in Moonraker?

In Octopussy, French idol Louis Jordan becomes the baddie Prince Kamal Khan and in The Living Daylights it is the turn of Dutch actor Jeroen Krabbe. Sophie Marceau is the big threat in The World Is Not Enough, a French seductress who’s also an evil mastermind – you just can’t trust such people.

In the Daniel Craig era, the European actors have multiplied and risen in star quality: from Mads Mikkelsen’s Le Chiffre in the Casino Royale remake, to Mathieu Amalric in Quantum of Solace, Javier Bardem in Skyfall and Christoph Waltz in the most recent, Spectre. Bond has long been licensed to kill EU citizens and one shudders to think that, if Bond were ever inclined to turn up at the ballot box, he might have voted for Brexit.

Of course Waltz has become the poster boy for Euro-villainy. It was his brilliant SS Colonel Landau in Tarantino’s Inglorious Bastards that put him on the map, so evil that he could speak three languages, which makes him a threat to the very fabric of American decency. He brought that European tinge to the claustrophobic critique of American bourgeois values that was Roman Polanski’s Carnage (don’t get me started on Polanski himself) and just this year, there was Waltz again as Belgian colonial exploiter Leon Blum, the villain in the Tarzan movie, so classically dastardly he would tie up Margot Robbie’s Jane on a paddle steamer.

The penchant for mistrusting a continental type in big movies has been alive and well for years. The first waves of emigres brought actors such as Peter Lorre, who’d become famous as a child molester in Fritz Lang’s M and brought a creepy sense of untrustworthy German-accented treachery with him to every role, particularly in Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon. In the wake of Nazi Germany, it was obvious why the baddies were played Teutonically for ages – even if, like Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man, they had to adopt over-the-top accents.

And of course during the long Cold War, Hollywood moved on to demonising Russians (especially ones played by, say, a Brit such as Alexei Sayle or a Scandinavian such as Stellan Skarsgaard). It’s a default position which has variously befallen also the Chinese, the North Koreans and now Arabs.

If I have a favourite European baddie, it might be James Mason as Phillip Vandamm in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, where it’s his velvet smoothness that threatens to out-smooth even Cary Grant.

Of course, most villains can only be defined by what they’re not, ie, they exist in contrast to the hero, to provide a mirror in which his essential all-American goodness can be reflected. Their badness is only measurable opposite the good guy’s virtue.

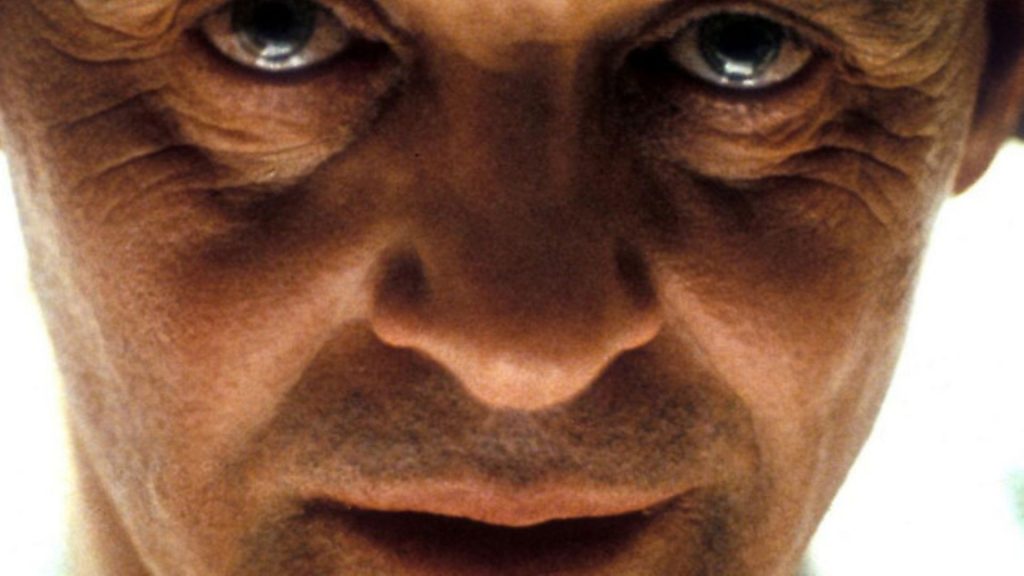

By that yardstick, Anthony Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter must be applauded for being a bad guy all out on his own (for the TV spin-off, Hannibal was played by the aforementioned Mads Mikkelsen), a man who even dines out with the deviant European flourish of fava beans and a nice Chianti.

An American can clearly not be seen to be an educated baddie; nor vice-versa, can an effete European be the leading man. This would upset the natural order for a Hollywood audience, for whom it must always be that, say, renaming a Quarter Pounder with Cheese should stand as an act of lily-livered treason.

Now European trends such as Brexit have been harnessed by Donald Trump to turn populism into a campaign-winning art form, one wonders if the Europeans can continue as the villains of the piece. After all, while the Chinese or Koreans or Russians may be angered by their portrayals, I don’t think Europeans or Brits particularly care if they’re the baddies in Hollywood. At least the devil always gets the best lines and the coolest outfits… and surely it’s still better than being an American.

Jason Solomons is a film critic, broadcaster and author of Woody Allen: Film by Film