Reginald Koettlitz was one of the heroes of polar exploration, yet found himself shunned and written out the story of his greatest exploits. GUS JONES explains why.

On January 10, 1916, in the small Karoo town of Cradock, South Africa, Dr Reginald Koettlitz passed away within two hours of his wife, Marie Louise Butez. He died of dysentery, she of heart disease.

For more than a decade, Koettlitz had been working as a country doctor in this remote region, often using a horse or pony-and-trap to call on patients in out-of-the-way places.

Such journeys would have presented little challenge for him, though. For in the years before he arrived in South Africa Koettlitz had travelled thousands of miles around the globe, and explored some of its most inhospitable places. He had been deep into the Arctic and, with Captain Scott, the Antarctic, and had also trekked through vast uncharted areas of Africa and, alone, up the Amazon to Manaos.

Yet, while other greats from this heroic age of exploration remain well-known names, more than a century on, that of Koettlitz has all but faded into obscurity.

It was a process that had begun long before his death. Indeed, his move to rural South Africa in 1905 was part of a withdrawal from the world of exploration in which he had been a leading figure.

It was not a deliberate retreat on Koettlitz’s part, though. During his final years in South Africa he still hankered for the chance to take part in one more great polar expedition. But by then Koettlitz had become increasingly alienated from the exploration establishment – a process which stemmed from his fractious relationship with Scott and criticism of his daredevil approach to polar expeditions, which ultimately led to his death on the ice in 1912.

While Scott was lauded and then eulogised, his former colleague Koettlitz was sidelined and then forgotten. It is high time that historical slight was corrected.

He came from an itinerant family which had moved from Konigsberg, in Prussia, to Germany, then Ostend, in Belgium, where Reginald was born in 1860.

His father was a minister in the Reformed Lutheran Church, his mother, Rosetta Dowdeswell, a English teacher. They were a family of some considerable wealth but had fallen on hard times as a result of the gambling debts incurred by a previous minister of the church.

Shortly after Reginald’s birth the family were on the move again, this time across the Channel to Dover, where his father resumed his duties as a church minister. Reginald, like his brothers, attended Dover College before qualifying as a doctor at Guy’s Hospital, London and Edinburgh University.

His first practice was as a GP and surgeon to mines in Butterknowle, County Durham. It was here he gained experience in treating not only common ailments but injuries sustained by miners in the open and underground workings.

But his horizons were broader than County Durham’s Gaunless valley and he secured an appointment as physician on an expedition – led by Frederick George Jackson and financed by newspaper proprietor Alfred Harmsworth – to the Arctic. Jackson had been misled by false maps into believing that Franz Jozef Land, an archipelago deep inside the Arctic Circle and only 500 miles from the North Pole, was in fact a land mass which reached the pole.

The Jackson-Harmsworth expedition involved three testing years spent on the islands. The group was only the second to live and survive on the archipelago.

One day, during their second year in the region, the group were startled by the sudden appearance of “a tall man, wearing a soft felt hat, loosely made, voluminous clothes, and long shaggy hair and beard”. It turned out to be the Fridtjof Nansen, the Norwegian explorer, who with his sole companion Hjalmar Johansen had been living on the ice since leaving their ship Fram more than a year earlier in an abortive attempt to reach the North Pole. It was chance that had brought Nansen and Johanssen to the Jackson-Harmsworth expedition camp and helped guarantee their survival.

As for Koettlitz, one of his main medical challenges during the expedition was to keep the men from suffering from scurvy. Their supplies soon ran low and they were forced to live from the land. This meant killing and consuming birds and animals which they found on Franz Josef Land. Polar bears in particular became a regular food source and more than 80 were killed during the expedition – providing nourishing dishes such as bear’s blood soup – along with hundreds of birds. Two sailors on the expedition ship Windward died from scurvy, having refused this diet, but none of the land party suffered from the disease.

It was an important lesson that Koettlitz was to take with him when he took part in Scott’s Discovery expedition to the Antarctic, from 1901 to 1904.

Koettlitz was appointed as senior surgeon for Scott’s trip and was also responsible for specific scientific duties. Prior to departure to the south he led the group responsible for equipment and provisions. From time in the Arctic Koettlitz knew the importance of using native Samoyed-type clothing, made primarily from Reindeer skin and fur.

But this English-based expedition ignored his advice, opting for ineffective man-made clothing, to the detriment and safety of the expedition members. But it was thought essential by the planners that personal tastes were catered for and under the title of ‘medical comforts’, 27 gallons of brandy and whisky, 60 gallons of port wine, 36 gallons of sherry and a similar amount of champagne were carried to the Antarctic continent. To enhance morale on the lower deck 1,800lbs of tobacco was also stowed away.

Having met Nansen on Franz Josef Land, Koettlitz had stayed in contact with the Norwegian and regularly sought his advice on matters relating to survival in the polar regions.

In their correspondence, Koettlitz was often scathing on the way the expedition was being organised, with Scott himself and Clements Markham, the president of the Royal Geographical Society, the target of particular criticism. “I fear there will be much blundering, waste of time and money, it will be muddled through à l’Anglais,” Koettlitz wrote, in remarks that were eerily prescient in the light of Scott’s ultimate fate. “How can men be such fools, men who have no knowledge of survival in the polar-regions?” he asked. He also wondered whether the men would take his advice to ‘live off the land’, eating seals and penguins to ward off scurvy.

As he feared, once they reached the ice his recommendations were often ignored and some of the men did develop scurvy, something Koettlitz was able to address by introducing his fresh meat diet.

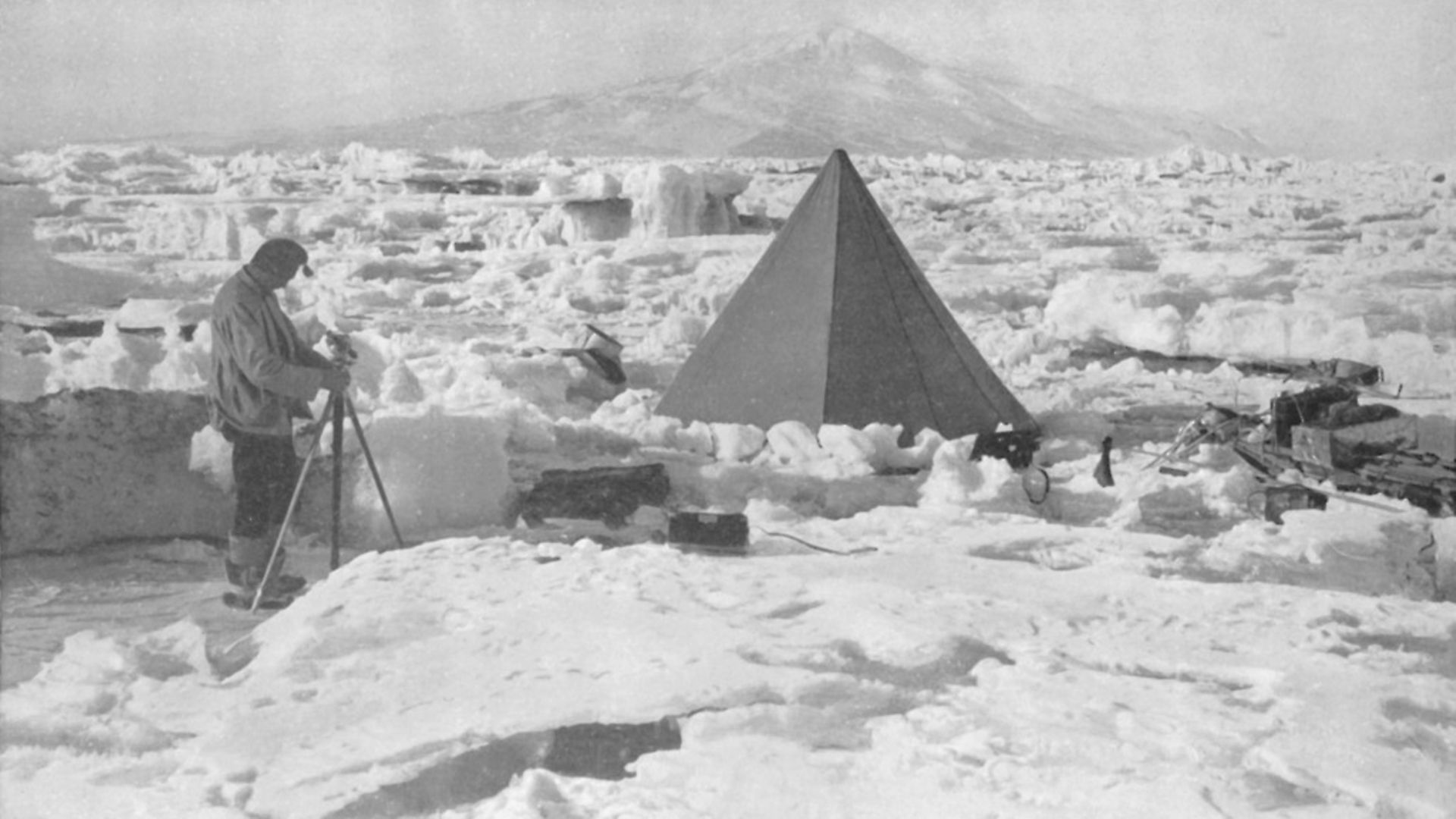

The main goal of the expedition was the exploration of the interior of the Antarctic land mass, which was at the time mainly unexplored. Koettlitz was deeply involved in this work. He made a series of epic sledge journeys from the base in McMurdo Sound where the Discovery was locked in the ice for the duration of the expedition.

His main sledge journey with Albert Armitage, who had also been a colleague on the Jackson-Harmsworth expedition, involved the ascent of the Transantarctic Mountains. The pair became the first men to step on the polar plateau, having reached a height of almost 9,000ft.

Other treks included sledge journeys to Black and Brown Islands, where he ascended to a height of 2,750ft discovering it was a volcanic cone and crater. These journeys and scientific discoveries were described in his extensive expedition journals and letters.

On return to Dover in 1904, Koettlitz gave one extended lecture in Dover Town Hall where he displayed the first colour images taken on the Antarctic continent. He was an accomplished photographer but, as with much with regard to Koettlitz, these images were handed to the expedition managing committee and have been lost to science and the nation.

It is a fitting metaphor for the way Koettlitz’s own story was overlooked. A clever but stubborn man, this polar explorer of great knowledge and experience suffered from an image problem from the very beginning.

His stubborn streak led to disagreements with Scott and a strained relationship. The pair would often play each other at chess during the expedition, with the eccentric surgeon’s victories causing Scott much annoyance.

Koettlitz was a serious man frustrated by those who lacked the same professional approach and therefore regarded by others as aloof and uptight. The idea of taking grease-paint to the Antarctic, to allow the men to stage morale-boosting shows, horrified him – as did playing football when they should be practising putting up tents.

Of course, critics would later point to Scott’s less than meticulous attitude as a contributory factor behind his death on the tragic Terra Nova expedition in 1912.

As something of an outsider on the expedition, therefore, Koettlitz was pushed into the shadows on its return. Although he had been made chief of scientific staff, his position wasn’t recognised in Scott’s book of the expedition, The Voyage of the Discovery. Worse, none of his work featured in the expedition’s final scientific reports. Even a report to the British Medical Journal was presented by Koettlitz’s deputy on the ship. This falling out with the polar establishment led ultimately to his move to South Africa, where he practised as the resident doctor in the expanse of the Great Karoo.

In Cradock there is a memorial to him erected by the residents of the region. There is no monument in England, just a polar bear shot by him on Franz Jozef Island now on display in Dover Museum.

To really find his fitting honours, though, you have to go to the ends of the earth: To the Koettlitz Glacier, one of Antarctica’s largest, and to Reginald Koettlitz Island, part of Franz Josef Land, both named in his honour.

A A ‘Gus’ Jones is author of Scott’s Forgotten Surgeon.