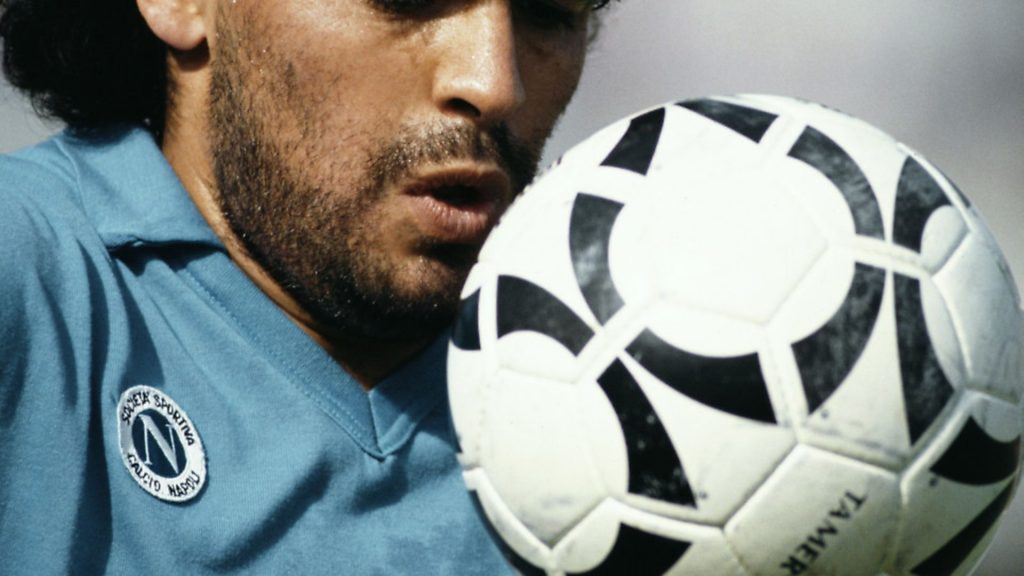

Diego Maradona’s spell with Napoli in the 1980s was a combustible mix of cocaine, the Camorra and some of the finest football ever seen. JASON SOLOMONS reports on the new documentary film which chronicles this extraordinary period

Volatile and glorious as it was, the explosive relationship between Diego Maradona and the city of Naples was always doomed to end badly.

The unlikely love affair between the two, however, forms the meat of Diego Maradona, the latest feature documentary from Asif Kapadia, completing a trilogy for the director – a perfect hat-trick, if you like – of films that began with Senna, about the life and death of Brazilian motorsport champion Aryton Senna, and resulted in Oscars for Amy, which followed the similarly tragic story of singer Amy Winehouse.

Along the way, Kapadia has revitalised the documentary scene, both artistically and commercially, turning the form into box office gold. And Diego Maradona is likely to be his biggest hit yet.

Of course the subject is one of the greatest footballers ever, certainly one the most revered and reviled, twin aspects which the film examines in detail, and which find their perfect environment in the crumbling, neglected, maligned Naples of the mid-1980s. Excitement, therefore, is high.

And the opening of the film doesn’t disappoint. I’m happy to make the bold claim for the first five minutes of this film as being the best opening sequence in the history of documentary film-making. We start with a breath-holding car ride, shot through the car front window, of a pretty battered vehicle swerving in convoy through the streets of Naples to a retro-electronic score. “We call it our French Connection shot,” says Kapadia and it really takes you directly into the atmosphere of the movie.

Intercut with the car journey is a magnificent montage of Maradona’s career, from keepy-uppys as a Buenos Aires street kid, to goal hero for Boca, to world’s most expensive player at Barcelona, to vicious hackings from defenders, to an on-pitch brawl and a horrific-looking bit of ankle surgery.

As the sequence ends, we realise where the car is headed: into the belly of Naples’ dilapidated stadium, where 85,000 Neapolitans have assembled to greet their new hero on the occasion of his signing for the club.

It’s a genius intro, setting up the mystery, the thriller, the horror, the glory of what’s to come. Maradona is whisked to a press conference where the first question is about his knowledge of where the money came from to make his signing. Was he, for example, aware of the influence of the Camorra, the region’s pervasive mafia?

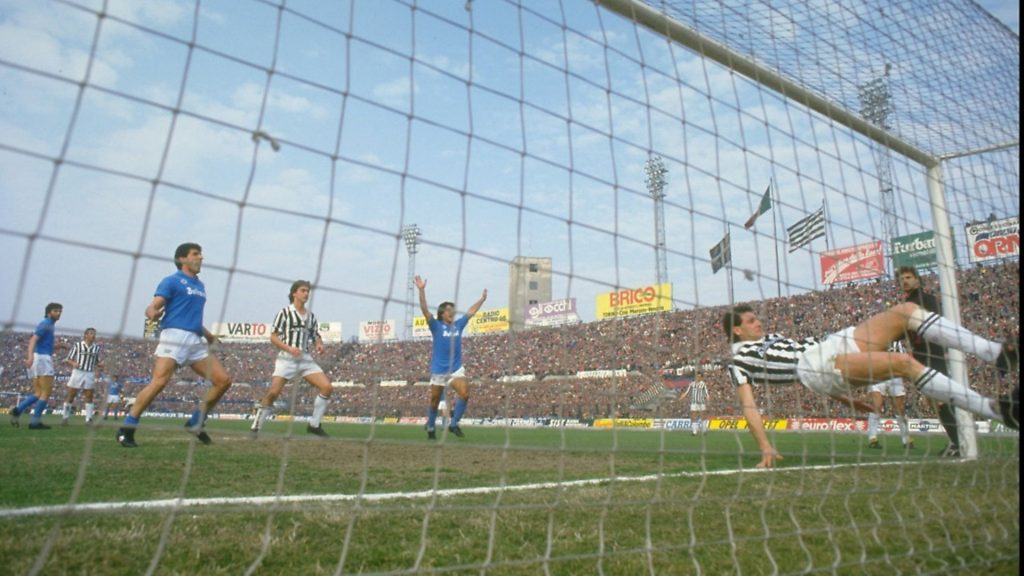

With hindsight, Maradona and Naples looks a perfect fit. Napoli were an outsider team, sneered at by the northern elite giants such as Juventus and the Milan clubs. Napoli had never won anything and Maradona set about almost single-handedly turning the fortunes of the club, and the city, around. He put them on the map.

“Some of the chants from the rival clubs were horrible,” says Kapadia. “They were racial insults, basically, accusing the Napoli fans of having cholera, stinking, needing a wash. The whole city was seen as a sump of poverty and corruption. Diego used the animosity as fuel.”

Some of the film’s best sequences simply let the football do the talking. Initially hacked down by traditional Italian defending, Maradona learns to adjust his game and gains in confidence, eventually skating over robust challenges and retaining his balance and channelling his energy into a relentless force of nature, he begins scoring and, then, winning.

As the film’s producer James Gay-Rees says, however, Maradona was always aware of the trap Naples could hold for him. “He was continually told he would be at risk of being kidnapped so he hired a camera crew to follow him around 24/7 as a kind of protection. They filmed everything – the operations, the training, the parties, the drugs, the family occasions, the birth of his children. But this footage had never been seen. We got it and, heavily edited down from hours and hours of VHS tape, it forms the bulk of the movie.”

The footage, shot by two Argentine cameramen, follows Maradona as he becomes ‘friends’ with the heads of the Camorra, the Giuliano family. “They offered him everything,” says Kapadia. “They protected him from the tax authorities, press, politics but they also gave him cocaine. Lots of it.”

Cocaine becomes a powering element of the story. We don’t see him actually taking it but, in a reflective voice over-recorded for the film, we hear Maradona talk about his experiences of it, from the first time he took it in a Barcelona night club (“I felt like Superman”) to his weekly use of it to celebrate victory on a Sunday.

“We’d play the match and then I’d go out to eat and drink and do cocaine,” he says of what became his routine. “I wouldn’t come home until Wednesday and then I’d start my cleanse, cleanse, cleanse to be ready for the next match on Sunday.”

Quite how he managed to maintain his sporting prowess throughout is a miracle. “How he’s still alive is basically a miracle,” adds Gay-Rees. And, according to Kapadia: “He’s had more comebacks than Jesus. Every time he looks like he’s finished, he bounces back.”

The journey in Naples includes the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, and those goals against England that mark him as a cheat and a genius. “The Argentinians actually value the Hand of God goal more,” says Gay-Rees. “They see more skill in getting away with the sleight of hand than they do in the beauty of the second goal.” The film makes no bones about Maradona seeing the victory over England as revenge for the Falklands.

But it also follows him through to the final, and to the sublime assist he provides his team mate Jorge Burruchaga for the winner against West Germany. I’d forgotten that one. “Amid the chaos, it’s the number 10 who must rise above it all,” says Maradona in voice over.

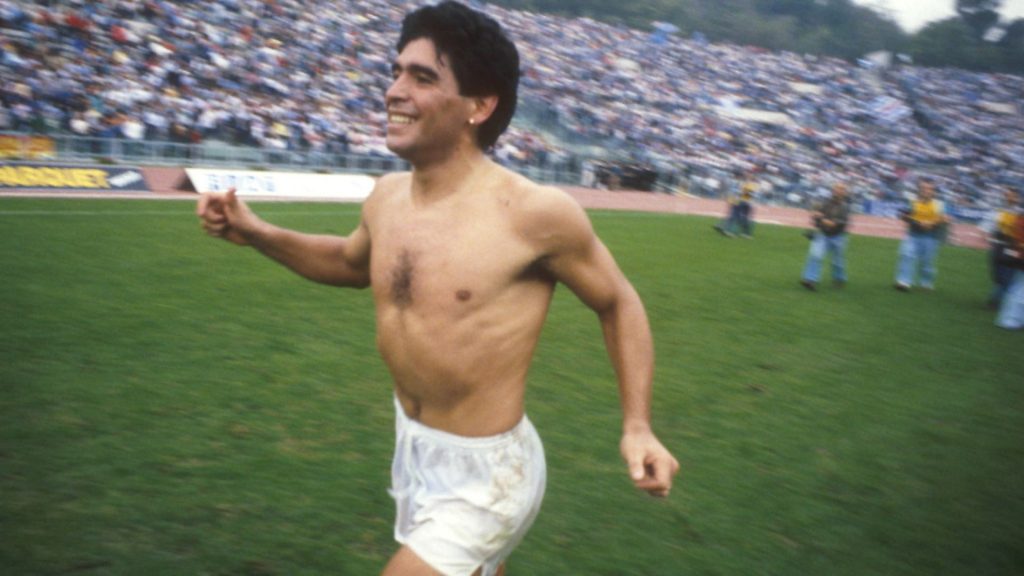

The euphoria of that World Cup win is impossible to ignore on the screen, even you’re an England fan still smarting over the handball. And the delirium that greets Napoli’s first scudetto – championship – is astonishing, the Naples streets teeming with people and cars and flags and chaos. “The party went on for two months,” recalls someone.

And that’s what the film does so well. It immerses you in the Maradona bubble. You feel the scything challenges and the constant noise of crowds and traffic. You begin to feel hemmed in by the pressure and the joy begins to fade from Maradona’s face, numbed by adulation and, as we now know, cocaine.

Kapadia says there were two people involved in the story, which is why he called the film Diego Maradona, as opposed the single monikers he gave to Senna and Amy: ‘Diego’ was the street kid who loved his mum, his sisters, his dad and his family; and ‘Maradona’ was the persona he had to invent to deal with the pitch and the fame. It’s a fine theory although, good as it may be, I still don’t know who it was hoovering up all the cocaine.

There’s still time for an extraordinary twist in the tale, the story of Italia ’90 and how Italy turned its back on Maradona. I’d forgotten this part of the story, so obsessed are we here in the UK by the story of Bobby Robson’s England, with Gazza’s tears and all that and that penalty shoot-out in Turin against Germany.

We forget that while this was going on, the bigger drama was the other semi-final, pitting home nation Italy against Maradona’s Argentina. A match that took place in, where else, Naples.

By this time, Maradona had become a enemy to many Italian football fans. His deliberate fuelling of the fires of animosity made him a hero in Naples, so much so that he thought he could exhort the Italian crowd in Naples to support him and Argentina against their own nation in the semi. It was a gamble too far, the moment Maradona found out he couldn’t count on their adoration any longer.

“It’s my favourite passage of the film,” says Kapadia. “It’s the knife-edge, the turning-point. And he steps up to take a penalty that might eliminate the home team from the World Cup they feel destined to win. You can’t make it up, drama like that. But we can embellish it, make it tense again, recapture the full pressure. That’s what we can build the whole story up to and I still have to look away every time I watch it.”

So many football fans know the story, remember it the first time around, that one can hardly call it a spoiler, but I still won’t reveal the outcome. Even after Italia ’90, there is a long way to go in the Maradona story and the end of the affair with Naples.

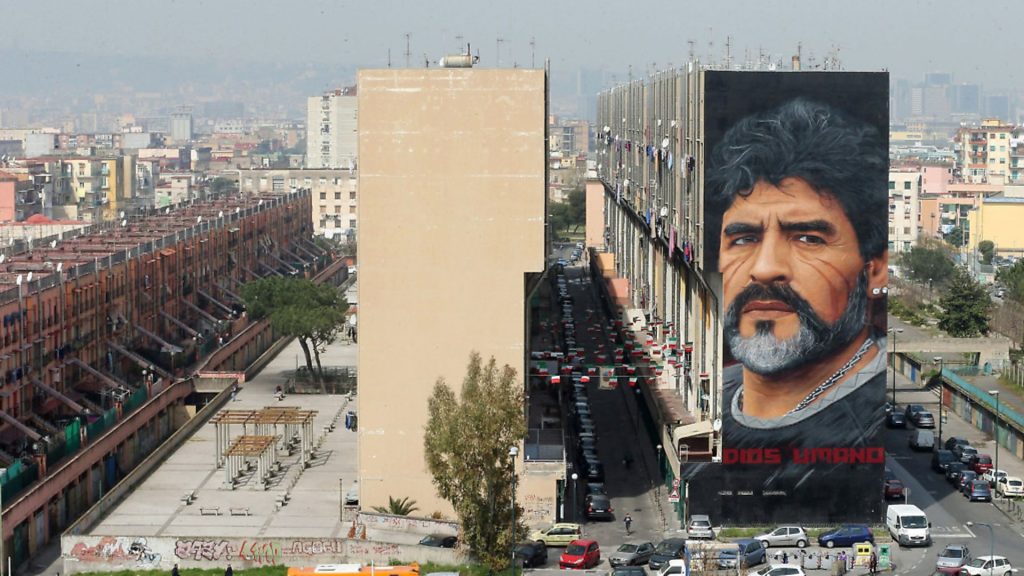

Despite a huge wire-tap operation involving prostitutes and mafia informants that brought the Giuliano family down and resulted in Maradona doing a flit practically overnight, he’s still revered as a saint there. You see the murals, the iconic paintings, the graffiti of a Madonna cradling an infant Diego.

The film, edited by Chris King, is also an exercise in memory, in how we capture the modern world, in television footage, grainy VHS, news archive, magazine front pages, newspapers and discussion shows. It’s about how we remember events and the way we portray our history.

Often, as Kapadia’s films show, the protagonist is the least reliable source – so much is happening to them, they have no way to see through the chaos that surrounds them and swamps them.

“Diego hasn’t seen the film yet,” says Kapadia. “I’d love to see his responses. I’m sure he’d deny our version of events, even though I’ve been meticulous in getting the facts as right as possible. He simply won’t see things from another angle. He sees things how Diego Maradona wants to see them.

“He was just as tough to pin down in real life as well as in terms of showing a definitive ‘character’ on screen. We’d turn up to Dubai where he was working at the time and we’d arrange an interview and get told at the door; ‘No, today’s not a good day for Diego, try tomorrow’. Same thing would happen the next day. He did eventually show up and I’d get a good 90 minutes out of him and sometimes he’d look at me and say: ‘You’ve got a nerve asking me questions like this – but I respect you for it.’ Inside, I’d breathe a huge sigh of relief.”

Kapadia adds: “He was supposed to come the premiere in Cannes, but couldn’t make it. He just didn’t get on the plane. And that didn’t surprise me.”

Maradona is currently managing a team based in Mexico’s drug cartel heartland. “Not ideal for someone with a recurring drug habit, but that’s him,” says Gay-Rees. “We could have added chapters and chapters, layers and layers of story, but we had to stop somewhere. The story of Naples and Maradona had it all: crime, money, romance, fame, drugs, genius and some of the best football an individual has ever produced. If someone keeps telling you’re a God, you do end up believing it. But we’re showing he’s a human.”

The family story, the cheating, the illegitimate children, the mistress, the prostitutes provide a constant background, an indication of temptation and flaws, occasionally touched by moments of sublime sport elevated to the beauty of art.

“It couldn’t last, and you wouldn’t want it to,” says Kapadia. “But it was wonderful while it did and I think we got all of that in the film.”

Diego Maradona is in cinemas now

Five Great Football Films

Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006)

More hypnotic work of art than footy movie, Turner Prize-winning film maker Douglas Gordon followed the French star, Zinedine Zidane, playing for Real Madrid, training 20 cameras on him throughout one match. We see the whole game through the eyes and movement of one man, building up a portrait of a man at work. The film, which climaxes with Zidane suddenly getting a red card, gained notoriety on release when Zidane exploded during the 2006 World Cup Final, head butted an opponent and got sent off – a case of life mirroring art?

Escape to Victory (1981)

Definitely the silliest and most fun football film ever made, as a team of allied prisoners of war plot to escape their German captors during a grudge ‘friendly’ in Paris during the Second World War. Director John Huston had never seen a football match before. And the football stars had never acted, including Spurs’ Ossie Ardiles, Ipswich’s John Wark and Russell Osman, England hero Bobby Moore, Brazilian legend Pele and, of course, Sly Stallone in goal. Michael Caine was captain. Still, I watch it every time.

Gregory’s Girl (1981)

A delightful evocation of young love, Bill Forsyth’s Scottish film became a treasured British classic. John Gordon Sinclair stars as geeky Gregory who loses his place in the school team to a girl, Dorothy (Dee Hepburn). Miffed but smitten, he tries to ask her out, but, after a series of strange encounters designed to test out his gentle characters, he gets set up with a different girl, Susan (played by pop star Clare Grogan).

The Two Escobars (2010)

Detailing the rise of ‘narco-soccer’, when the drug cartels laundered their money through Colombian football, this masterful and gripping ESPN doc entwines the life of drug lord Pablo Escobar with that of a Colombian defender named Andres Escobar (no relation). As Andres’ national team go on a winning run to qualify for the 1994 World Cup, they became a beacon for the nation. However, cocaine and politics intervene, inevitably, particularly when Andres scores a fatal own goal that knocks Colombia out of the competition. His return home to a country in turmoil ends tragically.

Fever Pitch (1997)

Maybe not the best film, but certainly a key book about football and fandom, Nick Hornby’s game-changing 1992 memoir made football respectable conversation in the UK. The film, starring Colin Firth as north London teacher Paul, reflects the emotional ups and downs of supporting Arsenal during their 1989 title-winning season, played out on the obsessive fan and on his burgeoning love for new co-teacher, Sarah (Ruth Gemmell). The climax, set to Van Morrison’s Bright Side of the Road, is unforgettable – especially if you’re an Arsenal fan.